brAIn drAIn

The enhancement and atrophy of human cognition go hand in hand

Unfortunately, there’s a growing subfield of psychology research pointing to cognitive atrophy from too much AI usage.

Evidence includes a new paper published by a cohort of researchers at Microsoft (not exactly a group predisposed to finding evidence for brain drain). Yet they do indeed see the effect in the critical thinking of knowledge workers who make heavy use of AI in their workflows.

To measure this, the researchers at Microsoft needed a definition of critical thinking. They used one of the oldest and most storied in the academic literature: that of mid-20th century education researcher Benjamin Bloom (the very same Benjamin Bloom who popularized tutoring as the most effective method of education).

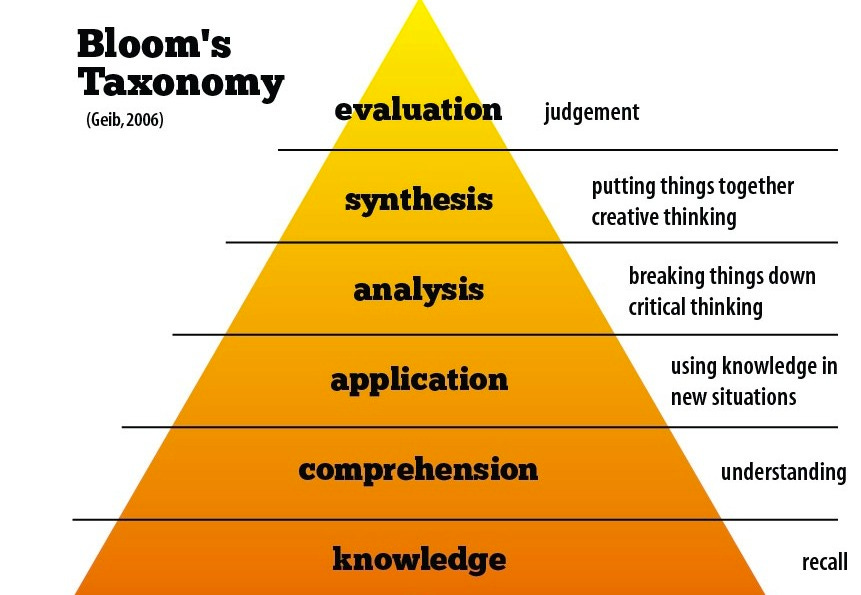

Bloom’s taxonomy of critical thinking makes a great deal of sense. Below, you can see how what we’d call “the creative act” occupies the top two entries of the pyramid of critical thinking, wherein creativity is a combination of the synthesis of new ideas and then evaluative refinement over them.

To see where AI usage shows up in Bloom’s hierarchy, researchers surveyed a group of 319 knowledge workers who had incorporated AI into their workflow. What makes this survey noteworthy is how in-depth it is. They didn’t just ask for opinions; instead they compiled ~1,000 real-world examples of tasks the workers complete with AI assistance, and then surveyed them specifically about those in all sorts of ways, including qualitative and quantitative judgements.

In general, they found that AI decreased the amount of effort spent on critical thinking when performing a task.

What’s interesting is that AI use does seem to shift the distribution of time spent within Bloom’s hierarchy toward the top; if you think about the above data in relation to the pyramid version, knowledge workers spent relatively more of their total time in the upper region of the pyramid when using AI, as effort at the top declined less relative to the other stages (in fact, evaluative refinement was the only place it increased for a number of users).

While the researchers themselves don’t make the connection, their data fits the intuitive idea that positive use of AI tools is when they shift cognitive tasks upward in terms of their level of abstraction.

We can view this through the lens of one of the most cited papers in all psychology, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two,” which introduced the eponymous Miller’s law: that working memory in humans caps out at 7 (plus or minus 2) different things. But the critical insight from the author, psychologist George Miller, is that experts don’t really have greater working memory. They’re actually still stuck at ~7 things. Instead, their advantage is how they mentally “chunk” the problem up at a higher-level of abstraction than non-experts, so their 7 things are worth a lot more when in mental motion. The classic example is that poor Chess players think in terms of individual pieces and individual moves, but great Chess players think in terms of patterns of pieces, which are the “chunks” shifted around when playing.

I think the positive aspect for AI augmentation of human workflows can be framed in light of Miller’s law: AI usage is cognitively healthy when it allows humans to mentally “chunk” tasks at a higher level of abstraction.

But if that’s the clear upside, the downside is just as clear. As the Microsoft researchers themselves say…

While GenAI can improve worker efficiency, it can inhibit critical engagement with work and can potentially lead to long-term over-reliance on the tool and diminished skill for independent problem-solving.

This negative effect scaled with the worker’s trust in AI: the more they blindly trusted AI results, the more outsourcing of critical thinking they suffered. That’s bad news, especially if these systems ever do permanently solve their hallucination problem, since many users will be shifted into the “high trust” category by dint of sheer competence.

The study isn’t alone. There’s increasing evidence for the detrimental effects of cognitive offloading, like that creativity gets hindered when there’s reliance on AI usage, and that over-reliance on AI is greatest when outputs are difficult to evaluate. Humans are even willing to offload to AI the decision to kill, at least in mock studies on simulated drone warfare decisions. And again, it was participants less confident in their own judgments, and more trusting of the AI when it disagreed with them, who got brain drained the most.

Even for experts, there’s the potential for AI-based “skill decay,” following the academic research on jobs that have already undergone automation for decades. E.g., as one review described:

Casner et al. (2014) tested the manual flying skills of pilots who were trained to fly manually, but then spent the majority of their careers flying with high automation (i.e., autopilot for much of takeoff, cruising, and landing). Procedural skills, such as scanning the instruments and manual control, were “rusty” but largely intact. In contrast, major declines in cognitive skills emerged, such as failures to maintain awareness of the airplane’s location, keep track of next steps, make planned changes along the route, and recognize and handle instrument systems failures.

In Frank Herbert’s Dune, the Butlerian Jihad against AI was a rejection of what such over-reliance on machines had done to humans. The Reverend Mother says:

“The Great Revolt took away a crutch… It forced human minds to develop.”

Outside of fiction, concerns go back to Socrates’ argument that a reliance on writing damaged memories, and span all the way to the big public debate in the aughts about whether the internet would shorten attention spans.

Admittedly, there’s not yet high-quality causal evidence for lasting brain drain from AI use. But so it goes with subjects of this nature. What makes these debates difficult is that we want mono-causal universality in order to make ironclad claims about technology’s effect on society. It would be a lot easier to point to the downsides of internet and social media use if it simply made everyone’s attention spans equally shorter and everyone’s mental health equally worse, but that obviously isn’t the case. E.g., long-form content, like blogs, have blossomed on the internet.

But it’s also foolish to therefore dismiss the concern about shorter attention spans, because people will literally describe their own attention spans as shortening! They’ll write personal essays about it, or ask for help with dealing with it, or casually describe it as a generational issue, and the effect continues to be found in academic research.

With that caveat in mind, there’s now enough suggestive evidence from self-reports and workflow analysis to take “brAIn drAIn” seriously as a societal downside to the technology (adding to the list of other issues like AI slop and existential risk).

Similarly to how people use the internet in healthy and unhealthy ways, I think we should expect differential effects. For skilled knowledge workers with strong confidence in their own abilities, AI will be a tool to chunk up cognitively-demanding tasks at a higher level of abstraction in accordance with Miller’s law. For others… it’ll be a crutch.

So then what’s the take-away?

For one, I think we should be cautious about AI exposure in children. E.g., there is evidence from another paper in the brain-drain research subfield wherein it was younger AI users who showed the most dependency, and the younger cohort also didn’t match the critical thinking skills of older, more skeptical, AI users. As a young user put it:

“It’s great to have all this information at my fingertips, but I sometimes worry that I’m not really learning or retaining anything. I rely so much on AI that I don’t think I’d know how to solve certain problems without it.”

What a lovely new concern for parents we’ve invented!

Already nowadays, parents have to weather internal debates and worries about exposure to short-form video content platforms like TikTok. Of course, certain parents hand their kids an iPad essentially the day they're born. But culturally this raises eyebrows, the same way handing out junk food at every meal does. Parents are a judgy bunch, which is often for the good, as it makes them cautious instead of waiting for some finalized scientific answer. While there’s still ongoing academic debate about the psychological effects of early smartphone usage, in general the results are visceral and obvious enough in real life for parents to make conservative decisions about prohibition, agonizing over when to introduce phones, the kind of phone, how to not overexpose their child to social media or addictive video games, etc.

Similarly, parents (and schools) will need to be careful about whether kids (and students) rely too much on AI early on. I personally am not worried about a graduate student using ChatGPT to code up eye-catching figures to show off their gathered data. There, the graduate student is using the technology appropriately to create a scientific paper via manipulating more abstract mental chunks (trust me, you don’t get into science to plod through the annoying intricacies of Matplotlib). I am, however, very worried about a 7th grader using AI to do their homework, and then, furthermore, coming to it with questions they should be thinking through themselves, because inevitably those questions are going to be about more and more minor things. People already worry enough about a generation of “iPad kids.” I don’t think we want to worry about a generation of brain-drained “meat puppets” next.

For individuals themselves, the main actionable thing to do about brain drain is to internalize a rule-of-thumb the academic literature already shows: Skepticism of AI capabilities—independent of if that skepticism is warranted or not!—makes for healthier AI usage.

In other words, pro-human bias and AI distrust are cognitively beneficial.

I thought the atrophy of human cognition had got well under way in recent decades before AI even got here!

Our prefrontal cortex are going to shrink. Fast. So let's hope the back of the brain can whip up something fun. I think about this a lot.