Plagiarism, aristocratic tutoring, emergence

Desiderata #2: links and commentary

1. The Intrinsic Perspective over the last month:

Why watch other people play video games? On the weird world of Esports.

AI-art isn't art: DALL-E and other AI artists offer only the imitation of art.

Secrets of the publishing industry: How to publish your book and get it attention, an anti-lesson.

2. In “Scientific Slowdown is Not Inevitable” it’s argued that perhaps ideas aren’t getting harder to find, and there are other reasons for the slowdown, including a decline of genius due to a lack of tutoring in education:

Our slow growth is a puzzle. We have generated huge amounts of useful knowledge. We have made it easier and easier to access this knowledge from anywhere in the world. We have Jstor and Google Books to dig through existing knowledge, and easy data analysis with Excel. We can collaborate with people all over the world through Zoom and Slack. And more people than ever are officially working on science, technology, and innovation. How is it that we are experiencing less progress despite all of these advantages, if it isn’t just that ideas are inherently getting harder to find?

One possibility is that there is a hidden factor that is driving research productivity to the floor. . . I will suggest three reasons for why. . .

One reason may be the unique child rearing that certain parents do – which appears to matter even though parenting and schooling normally show very small effects in studies of the population at large. For example, Laszlo Polgar, a Hungarian teacher, intensively trained his three daughters to become chess champions, and was successful with all three. One daughter, Judit, was the highest-ranked female chess player ever, and the only one to reach the top 10. Similarly, James Mill, the Scottish philosopher, politician, and friend of Jeremy Bentham raised his son John Stuart Mill to be perhaps the greatest British public intellectual of the Victorian era with a unique education. The educationalist Benjamin Bloom’s ‘two sigma problem’ suggested that such results were achievable with a large number of children if children were raised with one-to-one tutoring.

You may notice this is, even in its initial motivating setup, pretty much identical to my thesis in the recent “Why we stopped making Einsteins?” from March—except this new article doesn’t fully flesh out the idea and also makes it sound like an obvious previously-known consequence from Bloom’s research, whereas Bloom only studied the effects of tutoring on improving test scores within classrooms. AFAIK, he never speculated on anything like how the decline of genius is due to a historical decline of being raised with 1-on-1 tutoring (nor connected that to the decline of the aristocracy). Yet, my essay was not mentioned nor linked. Meanwhile, there are many other citations to similar online articles (and the author admitted to reading my piece on Twitter).

Now, I’m sure I’ll eventually be guilty of this same sin of omission. Everyone who writes online will be, at some point. It’s inevitable. And, as someone whose day job is to advance novel scientific hypotheses, let me just say that figuring out who actually came up with an idea (vs. just who said it latest) is always basically impossible to adjudicate outside of really specific things like mathematical proofs. I’m not 100% sure that the point on aristocratic tutoring is original to me—it was original in its inception, but perhaps it’s obvious to someone, somewhere, who has read or written something else I never saw—surely it was obvious in some way to the many who did it historically! And nothing is ever truly original anyways, since ideas are all combinatorics and recontextualizations—it’s not bad to give credit to someone who presents an idea in its convincing totality, even if parts of that idea can be found scattered in other places.

But this brings up the broader problem: what are the things you should cite when writing online? For blogs, newsletters, and outlets, I mean. The easy answer is to cite everything that should be cited—but that’s impossible! In fact, most outlets will purposefully not cite other’s work: click on a link in the NYT and four out of five times it will redirect you to some other NYT page. Such outlets are closed informational ecosystems, with absolutely zero interest in anything like good citation or crediting (strangely, their zealous commitment to not crediting anyone for anything does not affect their prestige).

In the scientific literature, if the subfield is small enough, it might occasionally occur that a paper cites what it, in an ideal world, should. But most of the time even scientific papers fail on this. So what hope does an online essay have, especially about big or broad subjects, like the nature of education or the decline of genius or whether ideas are getting harder to find? And not only that, sometimes people feel they should be cited, when it doesn’t really fit, so it’s tough to trust your own perceptions, since you’re always biased toward overestimating your own impact and originality. I’ve had one or two people email me about my writing and ask—why didn’t you cite my work on this?—and I’ll be honest, so far it’s mostly been something only tangentially related, or a point so broad it’d be ridiculous to assign priority to (e.g., maybe social media is bad for us, maybe AI is dangerous, or other common tropes).

I wish I had a perfect solution for this problem of citation when writing online. I.m.o., a citation (via at least a link) to other pieces is indicated when the work passes a certain threshold of recency multiplied by relevancy. Should I be scouring blog posts from fifteen years ago to cite? Eh, perhaps not so much. Unless it’s quite literally exactly the same, it’s just too high a standard to uphold. And even if it is the same, online pieces are all living documents—if you end up rediscovering someone else’s piece almost exactly, or toeing the line of what in academia if left uncredited would be plagiarism, you shouldn’t worry too much—yes, it’s fair for the author or a reader to leave a comment saying “Hey, what about this?” but it’s also fair for you to just add in a citation (even if the mention is just a tiny cf. in a footnote) and simply say to the commenter or author who asked: mea cupla, missed this, mea culpa. The author can also debate or defend themselves, saying that actually the citation is not warranted, e.g., it’s too broad and so laying claim to such an idea would be ridiculous, or find earlier sources, etc. These are certainly my standards, a code I choose to live by because I think it’s the reasonable one that works. We shouldn’t make it so authors have to do things perfectly, because then nothing gets done. When I privately reached out to the author of the article, Ben Southwood, to point out that he had written up a miniature version of the exact same thesis to something he had recently read but was not citing, he replied he thought he had cited it and put a link in.

3. Speaking of that essay, I was able to discuss the aristocratic tutoring hypothesis with Palladium magazine, who hosted me on their podcast.

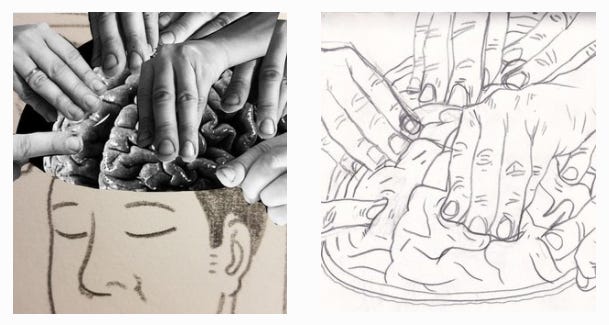

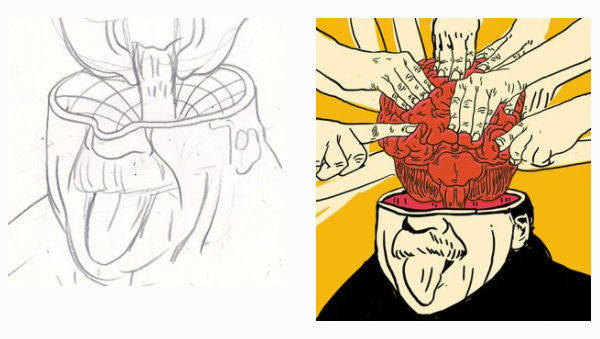

4. Also related: a reminder that the artist who does the illustrations for The Intrinsic Perspective, Alexander Naughton, is open for commissions. He wrote up a description of his process, which shows how much work goes into these:

Usually, I get a minimum of two weeks to deliver an illustration but I turned this one around in two days.

First were the initial sketch ideas. Erik liked the idea of the brain being molded so we went with that. Usually I like to come up with at least two ideas but to be honest, this seemed perfect for the essay.

Next I developed the idea by creating a digital collage of my hands massaging a brain. I then drew the collage by hand and scanned the drawing.

I knew I needed something else to give the image some reference to the essay. Then I remembered that famous picture of Einstein with his tongue out. I thought that would be the perfect reaction to a bunch of disembodied hands probing and molding his brain.

I added all the sketches together on photoshop and traced over it digitally. The final addition to the image was the curved and coloured lines inside Einsteins neck to reference curved spacetime, his genius contribution to physics. Erik loved the illustration and his essay went viral.