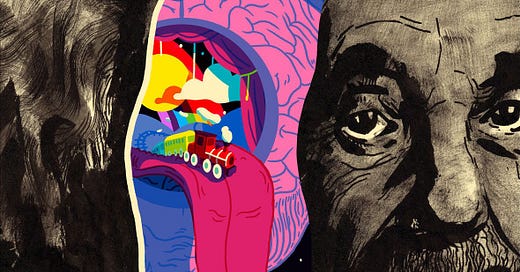

Great scientists follow intuition and beauty, not rationality

The unreasonable effectiveness of aesthetics in science

Isaac Newton’s lifelong quest to transmute base metals into gold is normally forgiven as a symptom of the pre-scientific nature of his age. But “great minds holding eccentric, even kooky, beliefs” is a pattern that crops up throughout history. Even after there became strong social reasons for scientists to disguise even the faintest whiff of the irrational. William James, the godfather of psychology, believed in ghosts. Fred Hoyle, who came up with the idea that stars created chemical elements via nuclear fusion, thought that influenza came from space. Nikola Tesla was obsessed with the number three. Nobel Prize winner Wolfgang Pauli believed that his mere presence could drive laboratory equipment to malfunction. Kurt Gödel starved himself to death out of fear of being poisoned. Brian Josephson, a still-living Nobel laureate, thinks that water has memories.

Why?

In the “TV model” of science, scientists are pinnacles of rationality—socially inept, boringly nerdy, emotionless, and incapable of strong pre-evidence beliefs. You can also find this view expressed in places like Steven Pinker's latest book, Rationality, in which he argues:

It has become commonplace to conclude that humans are simply irrational—more Homer Simpson than Mr. Spock. More Alfred E. Newman than John von Neumann… To understand what rationality is, why it seems scarce, and why it matters, we must begin with the ground truths of rationality itself, the ways an intelligent agent ought to reason, given its goals and the world in which it lives.

Pinker’s reference of John von Neumann makes sense, because von Neumann has lately become the poster child of genius, which in our metric-obsessed age means an IQ stratospherically high coupled with “rational” thought practices.

Yet it is actually fitting that for the public the most famous scientist remains Einstein, not someone like John von Neumann. Oh, there are arguments to be made that John von Neumann was more intelligent than even Einstein. Tutored far more intensely from a young age, homeschooled until 10, given governesses and access to advanced private math mentors, he had a wider knowledge base than Einstein, and was certainly much more rational (kind of obvious from being a pioneer in game theory). Leading people to spark viral debates online with things like this:

But von Neumann himself? He felt he lacked a certain quality as a scientist. Here’s from a profile in The New Republic:

In his work… von Neumann never had strokes of irrational intuition, the kind that result in startling new ideas; his friend Einstein had many, and von Neumann envied them.

He understood that there was not just one thing, rationality, that describes good thought. If that were true, scientists should be immaculately rational, and the greatest scientists should be even more rational than merely the mid-tier of non-greats, and so on. Tellingly, von Neumann supposedly blamed himself for missing out on a number of fundamental insights (incompleteness, the Dirac operator, etc) in the many fields he touched, despite being close every time.

Meanwhile, Special Relativity was just that, special. Oh, people will argue over antecedents, but the reality is no one made anywhere close to the same conceptual leap, even if they were at the time playing around with parts of the same math. To everyone else, it seemed as if Einstein had somehow plucked an idea from the gods and put it into human hands. Really, he had plucked it from some sort of netherworld of pre-scientific intuition.

Scientists are not big spheres of rationality. They are spiky and make use of intuition and aesthetics. Get scientists talking over a few beers, and you'll see. You’ll see that their little spiky bits of irrational attachment make them more interesting, and more effective, than their duller peers.

For despite the best efforts by philosophers and scientists, there is still no clear solution to what's called the demarcation problem: knowing where science exactly begins and ends. Attempts to define science as merely an abstract machine for falsification, like Karl Popper did, leads to the problem of exactly how one chooses which hypotheses—of which there are infinite—to try to falsify.

In other words, the abstract machine of science is an open system. We can be rational about choosing between different hypotheses, or choosing between different ideas, or choosing between different experiments. But rationality does not actually tell you, by itself, what makes for a good hypothesis, a good idea, or an elegant experiment. Those choices include some strange blend of aesthetics, intuition, passion, and other irreducible qualities.

So there is “Science” in its formal buttoned-down form described in textbooks, and then there is the pre-theoretical fringe that drives science forward and gives it its momentum; its ultimate demiurgic force. It is only this tectonic zone where the pre-scientific and scientific meet that can ever expand the borders of knowledge.

Why does this work? Because beauty is truth, and truth beauty. Much like Eugene Wigner famously argued that there is an irrational and unreasonable effectiveness about how well mathematics can be used in the natural sciences, so too is there an unreasonable effectiveness for psychological traits (like an appreciation of beauty, intuition, etc) when it comes to the pre-theoretical fringe that progresses science’s borders. Wigner's argument was not broad enough: math is beautiful, and that is why it is unreasonably effective (pulchritudo splendor veritatis).

In this view, great scientists try to force their intuitions and aesthetic conceptions onto science itself, often in ways that lead to incredibly successful breakthroughs but then fail wildly other times. A perfect example is someone like Fred Hoyle, who has a very strong intuition that can be summed up as: “Maybe the sun is responsible!” An intuition which works wonders for chemical elements via nuclear fusion, but despite his best efforts at argumentation, probably doesn’t work for something like influenza, which does not come from space.

So we can see how that same intuitive drive behind scientific progress can be limiting—once used, it cannot be foresaken. “God does not play dice with the universe!” Einstein was absolutely certain of that. And he was certain of it because he thought that some aesthetic dimension of his mind fit well with the universe. The mathematical term for it is congruency—when one shape, laid atop another, reveals their identity. Or as the kids would say, he was vibing with reality. But that congruency, that vibing, earlier so perfect, became mismatched; which is why he introduced the cosmological constant, and didn’t discover the Big Bang 50 years earlier. In this Einstein's spikiness failed him.

But, here’s my counterpoint: physics isn’t over. Would it not be the ultimate vindication if, in 100 years, our picture of the universe looked much more like what Einstein envisioned? Matching, finally, the aesthetic order that pleased him?

T’would be a strange groove of a brain, to tell the future so.

One thing I didn't point out here, but is well worth pointing out: Currently, our academic system (which is supposed be a meritocracy) has far fewer ways to measure things like "aesthetics" or "intuitions." Therefore, potential great scientists get passed over for more competent grade grinders.

The word 'intuition" is used several times in this essay. I wonder if intuition is essentially an artifact of a rational process enabling the brain to build a mental model that generates insights.