High-tech pastoral as the new aesthetic

Explaining a common taste of aging millennials

What is high-tech pastoral? I ask because it explains the behavior of my generation, the millennials, as we age. I used the term first in “Remote work is the best thing to happen to families in decades” from earlier this year, albeit passingly, and without expansion. But it’s important to define, for without it my generation’s behavior, not to mention the current housing market, appears rather inexplicable.

Unfortunately, all definitions are tautologies—look up any word in the dictionary, read its definition, and then look up the words within that definition in the very same dictionary. Keep repeating this until you arrive back where you started.

So we must give examples, and allow the brain to work the magic it does when it goes beyond words and sniffs out vibes.

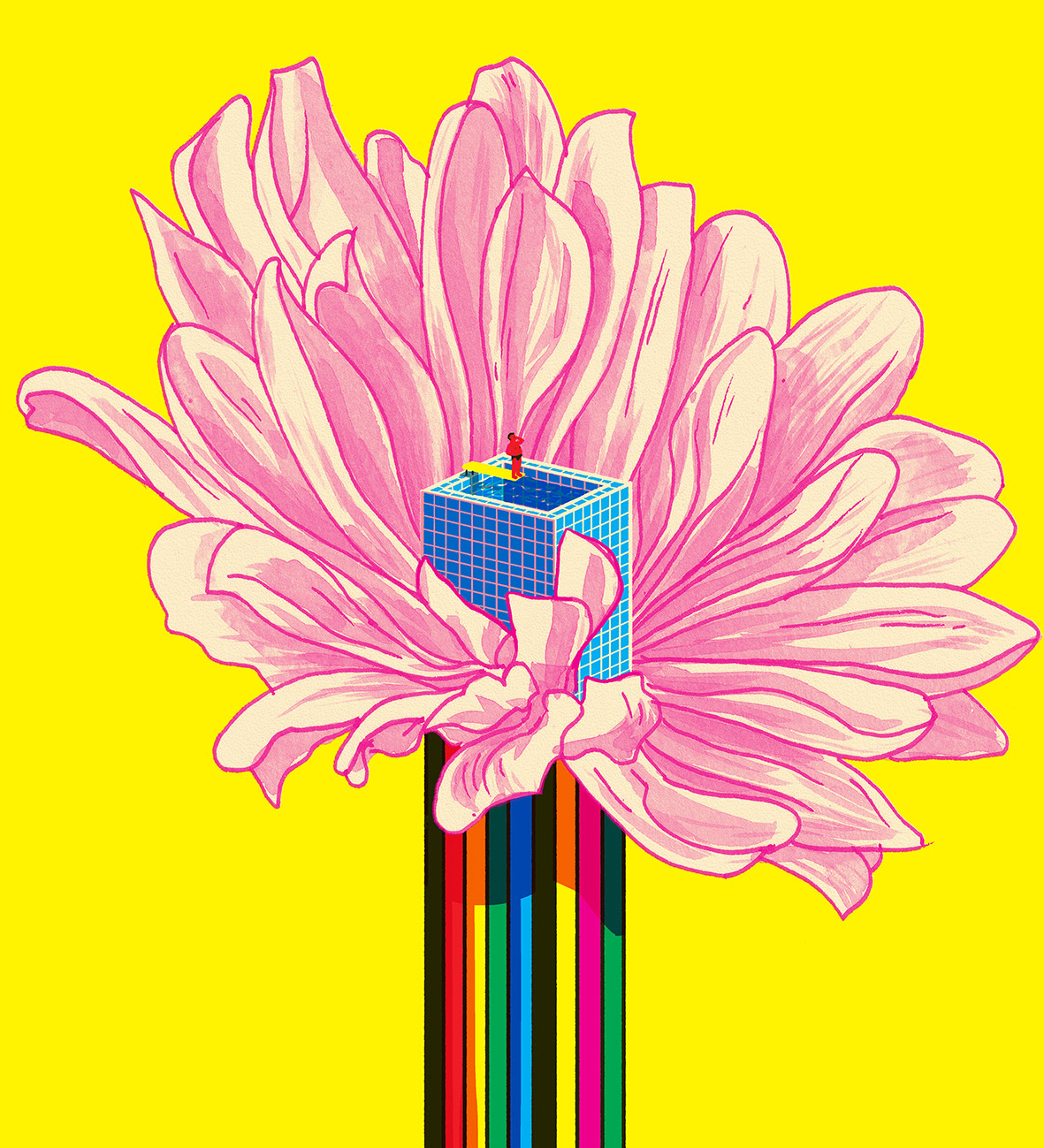

Simple cases: taking a Zoom call in your home office. Pajamas underneath a suit jacket, just out of frame. There are trees out the window. Another example: sitting on a porch, laptop in lap, a drink within reach. A work call while walking the dog in the middle of the day. Sending an email at the beach. Typing with hands stained with Earth from being outside. A green world reflected in the blue of the screen. Sand on an iPhone. Available, simple, everyday things.

One can go more extreme. Imagine a laptop sitting on a picnic table under the shade of an apple tree. Zoom out from its Apple logo and find an orchard stretching into the distance. A hawk circles overhead. Or imagine Facetiming someone on horseback (here, make sure to picture the brightness and the motion as the rider pans around, her helmet and smiling face, the jealousy and irritation of the others on the call). Only the future knows the limits—it is suddenly easy for us all to picture a man talking to an AI assistant on a sailboat. Or the aesthetic can be pared down to the minimal modern core of a Starlink dish flashing white on the roof of a camper van parked in the woods. Or it could be a woman taking off a sleek VR helmet and its display of financial information and then, with a few barefoot steps down the hall, emerging out into an old-world dilapidated terrace, blinking, eyes adjusting to a Mediterranean view.

What do you feel at such examples? Annoyance? Exasperation? Attraction? Neutrality? Sadness? Desire? A mix? Should people even be paid for this? some ask.

For it should be obvious that at its most extreme high-tech pastoral is a sort of techno-aristocracy—by this I do not mean it is solely or necessarily for the rich, but rather it is aristocratic in mood, in that it is mentally connected to the online frenzy but physically unrushed, almost indolent. It is a kind of lounging, metaphysically, a playfulness and enjoyment of both the online world and the natural one. For that is what being on permanent vacation is: a kind of lounging. Yet it is not vacation. And yet it is.

Within capitalism it is always the secret dream of the bourgeois to transform, swan-like, into aristocrats. And if we are to judge by the housing market, something like high-tech pastoral is now the new bourgeois life target. For millennials, it is the out people are taking.

If the suburbs is a housing situation defined by a commute, high-tech pastoral is a housing situation defined by remote work. The reasoning is obvious, almost not worth stating: if you can work anywhere, why go along with some cramped and expensive living situation? As with so many social changes, it is a desire enabled by technological progress. For there is a laptop class in the United States, and laptops fit in laps. Companies and tech leaders can fight this all they wish, and bosses may pine for a return to at-office work, but Covid let the horse out of the barn. It too has left for the pastures, a horse-sized wireless earbud in place.

But technology alone does not quite explain the phenomena, the aesthetic itself. That is the positive drive. There is also a negative one. For the bourgeois desire for the high-tech pastoral life is pushed forward not just by the miniaturization of our recording equipment, nor by the fidelity of our cameras, nor by the decreasing pings of our cables, but rather the fall from grace of pastoral’s antithesis: the American city.

You know of what I speak. The rents are higher. The crime is higher. The downtowns are still bled from Covid. Zoomers, who just now should be hitting the cities en mass, seem less interested in night life, bars, or even physical events at all. They have their own weirding ways. And while there will always be enough bright young things to revivify a place like New York, what about other, mid-tier cities?

Perhaps this supposed decline of the American city isn’t even real. Perhaps it’s just on our phones. The thing is that it doesn’t matter. Let’s be blunt: a lot of people are scared of cities from short clips of shambling drug addicts they see on social media, and the stories they read about death on the subway, drug use, stranger danger. What matters is perception. Those who do live in the real San Fransisco, whatever their opinions, are in the minority when it comes to the perception of the imaginary San Francisco that lives in everyone’s head. Which is becoming ever more negative with every video of a slow drive past tents upon tents and every frustrated social media post about a broken car window—whether that reflects everyone’s lived life or not.

In a reductive view, humans behave a lot like salmon. We spawn, travel great distances to find a mate, then return to our hometown, or our mate’s hometown, or somewhere thereabouts, just to spawn again. Maybe it is more than an analogy—perhaps we too have secret magnetic field detectors, just like salmon, left-over and undiscovered by neuroscientists, that draw us home. In this the new high-tech pastoral aesthetic is not a historical anomaly, just the latest iteration of a tale as old as time. You certainly don’t have to cast movement from cities as some sort of deep political or philosophical stance. All the material causes are right there. People need space, families need space, and owning a good-sized house in a small town is far cheaper than owning a tiny apartment in the city. Everyone knows this.

Still. The material causes can be accounted for, but cultural changes, movements, subliminal messaging in what is attractive and found worth wanting—these things matter. They are the Aristotelian “final causes” of human behavior, the meanings and reasons. The kind of personalized and unique life enabled by remote work, and the desire for one’s own version of that, does seem fundamentally different from the commute-based suburban dreams of the 1950s. It has a different vibe, like some point of emphasis has shifted. A new set of images and feelings takes over.

For what is an aesthetic, anyways?

It is a fashion that asks a question.

And what question does high-tech pastoral ask?

What is the purpose of technology, if not to make life easier and more beautiful?

reading this on my vision pro while taking ayahuasca in my homemade ice bath, surrounded by horses that have learned how to use ChatGPT to make their work easier, and I gotta say, I agree

Technology is double-sided. While making life easier/more beautiful, it also distracts us from the realities (miseries?) of self-conscious existence. Eg, porn, video games, mindless YouTube videos, etc. are prime example of this distractive aspect of technology.

Things are always getting better and always getting worse. Confucius didn’t say that, but an astute professor of mine did. Maintaining the balance in order to live a meaningful, examined--dare I say, distinctly human!--life seems to be the main struggle of our bourgeois techno-affluence.