If serotonin isn't linked to depression, why do SSRIs even work?

On the paradoxes of biology

The blockbuster scientific article of last summer, “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence,” sparked a wave of analysis and debate, since it found no evidence that the serotonin theory of depression is actually true. Overhanging it all was this question: How is it possible that both (a) SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) have positive reported effects on depression, and (b) serotonin has nothing to do with depression? That is, how can people say things like this:

and write articles in Vice like this one:

In the wake of the article in Science, plenty have defended psychiatry and neuroscience, claiming that no one really believed in the “chemical imbalance” theory anyways. Here’s from the Vice article:

In the face of this story, it’s easy to understand how a new paper in Nature Molecular Psychiatry this week seemed like a bombshell. In a systematic review of studies on serotonin levels in people with depression, it found no evidence that depressed people had lower serotonin levels or abnormal serotonin activity compared to non-depressed people.

But the serotonin story of depression was just that: a story. It was a hypothesis that turned into a simplistic representation of a guess about the underlying causes of depression and how to “fix” it. Researchers and clinicians, in their responses to the review, said this theory hasn't been widely held by the mental health community for some time.

Yet, in graduate school for neuroscience I would say the “serotonin theory of depression” was the most common theory, in fact, merely one pulled from a class of similar theories about brain function in general. The assumption being that brains have a neuromodulatory milieu (including serotonin) and changes in the “balance” of this milieu was the cause behind mental disorders like depression (among many others). Consider the opening paragraph of that Science article showing a lack of a link, which gives a run-down of how common the standard view is:

The idea that depression is the result of abnormalities in brain chemicals, particularly serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT), has been influential for decades, and provides an important justification for the use of antidepressants. A link between lowered serotonin and depression was first suggested in the 1960s [1], and widely publicised from the 1990s with the advent of the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants [2,3,4]. Although it has been questioned more recently [5, 6], the serotonin theory of depression remains influential, with principal English language textbooks still giving it qualified support [7, 8], leading researchers endorsing it [9,10,11], and much empirical research based on it [11,12,13,14]. Surveys suggest that 80% or more of the general public now believe it is established that depression is caused by a ‘chemical imbalance’ [15, 16]. Many general practitioners also subscribe to this view [17] and popular websites commonly cite the theory [18].

So it’s not all just the public, media, and drug companies, it’s actually the theoretical lens through which a lot of scientists understand the brain.

The debate recalls the infamous Tom Cruise interview. In it, Cruise argues that psychiatry is a “pseudo-science” and that “there is no such thing as a chemical imbalance.” In the interview, journalist Matt Lauer pushes back, immediately responding that these do work for some people, and Cruise doesn’t really have a good reply to this.

Despite the performative nature of the public debate, it’s actually a pretty good representation of the problem that even experts face when confronting these issues. The problem is that we are stuck between: “None of the neural mechanisms of the drugs seem to have obvious links to the etiology of the disorder” and “People on drugs often get better, therefore we must be doing something right.” Like many things in biology, this seems paradoxical.

Sure, there’s an obvious answer in terms of the placebo effect—maybe the drugs do nothing at all! And indeed, the difference between antidepressants and placebos has been decreasing over time:

Antidepressant–placebo response-differences (RDs) in controlled trials have been declining, potentially confounding comparisons among older and newer drugs. For clinically employed antidepressants, we carried out a meta-analytic review of placebo-controlled trials in acute, unipolar, major depressive episodes reported over the past three decades to compare efficacy (drug–placebo RDs) of individual antidepressants and classes, and to consider factors associated with year-of-reporting by bivariate and multivariate regression modeling. Observed drug–placebo differences were moderate and generally similar among specific drugs, but larger among older antidepressants, notably tricyclics, than most newer agents.

Still, as noted, many types of study designs, like randomized controlled trials, can significantly or completely attenuate the placebo effect, and they do show positive effects of SSRIs when compared to placebos—this difference has just become more moderate and less impressive over time.

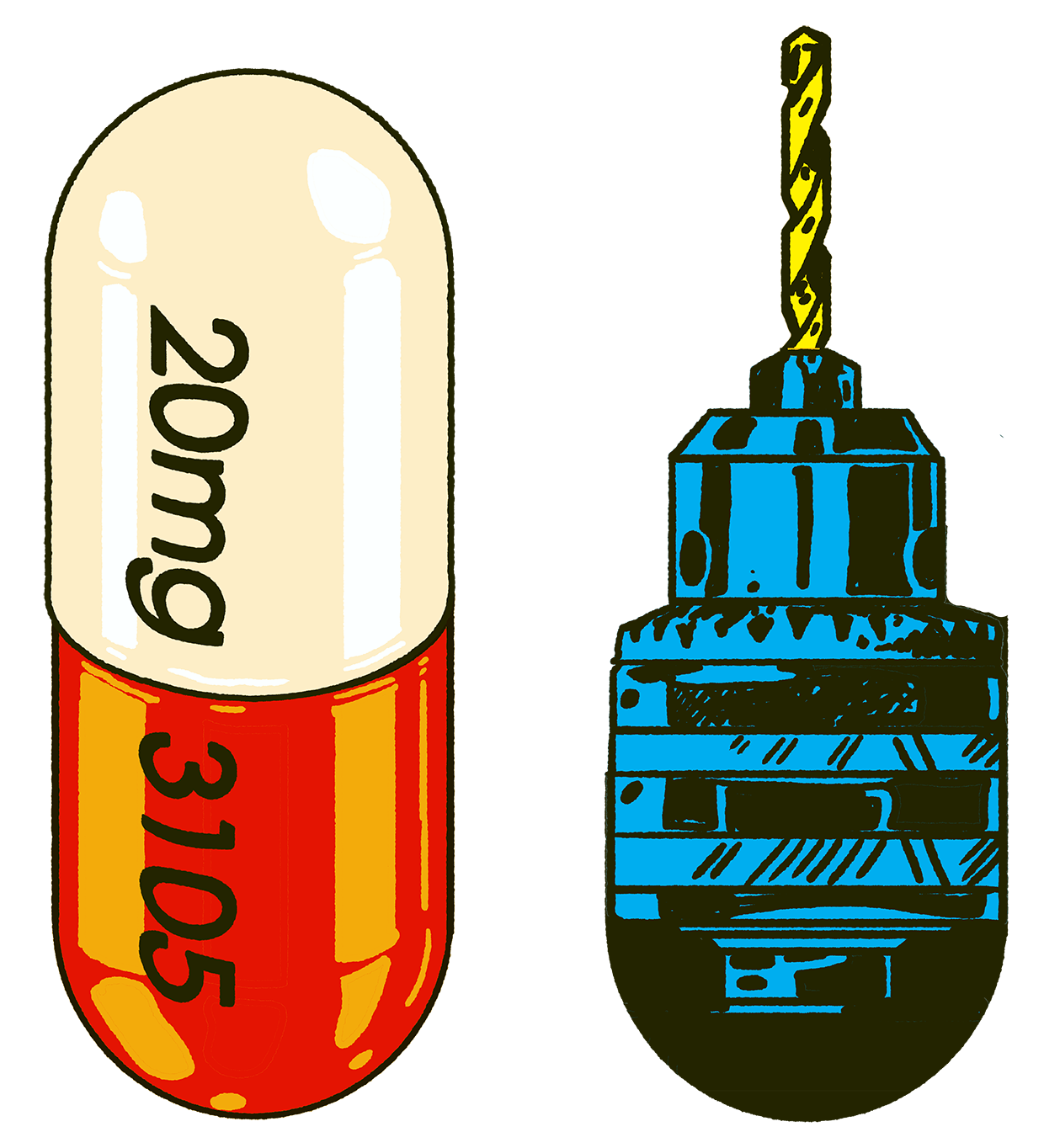

But assuming that these drugs do do something, what could be the explanation? How could a drug work without having any connection to the underlying etiology? And what does this tell us about why biology is so paradoxical? I think there’s a simple toy model that’s helpful. One that also just happens to explain why really weird and grisly interventions, like medieval trepanations, may have actually worked to treat mental disorders in much the same way, above and beyond the placebo effect.