It Only Snows Like This for Children

The Lore of the World: Snow

The first short story I ever wrote was about a teenager who goes to shovel his grandmother’s driveway during a record snowstorm. Before leaving, he does some chores in his family’s barn, bringing along his old beloved dog. But he forgets to put the dog back in—forgets about her entirely, in fact—and so walks by himself down the road to his grandmother’s house. Enchanted by the snow, he has many daydreams, fantasizing about what his future life will hold. After the arduous shoveling, he has an awkward interaction with his grandmother. Finally, hours later, he returns home. There, he finds his old beloved dog, curled up in a small black circle by the door amid the white drifts, dead.

I don’t know why I wrote that story. Or maybe I do—I, a teenager just like my main character (including the family barn and the grandmother’s house down the road), had just read James Joyce for the first time. And Joyce’s most famous story from his collection Dubliners, “The Dead,” ends with this:

Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

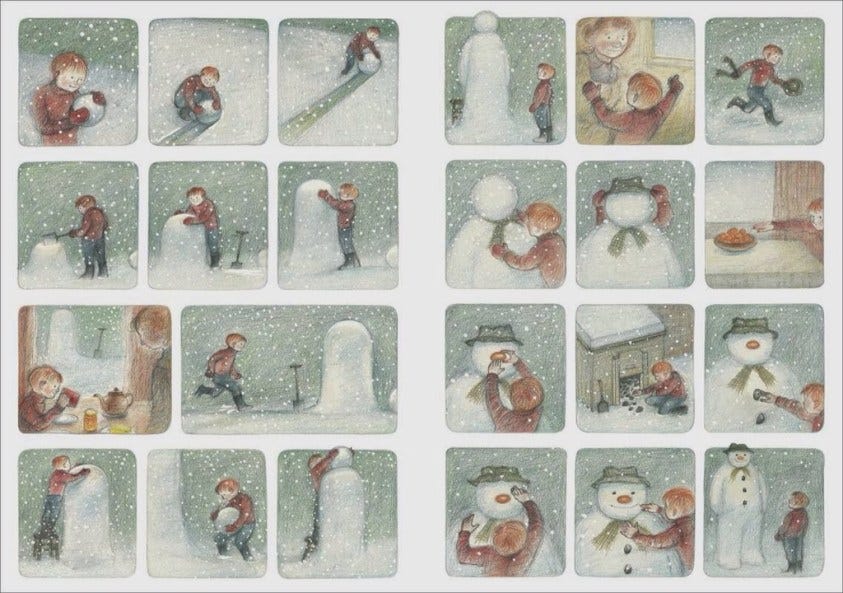

Snow is the dreamworld, and so snow is death too. It’s both. The veil between worlds is thin after a snow. One of our favorite family movies is the utterly gorgeous 1982 animation and adaptation of The Snowman. Like the book, it is wordless, except the movie begins with a recollection:

I remember that winter because it brought the heaviest snow that I had ever seen. Snow had fallen steadily all night long, and in the morning I woke in a room filled with light and silence. The whole world seemed to be held in a dream-like stillness. It was a magical day. And it was on that day I made the snowman.

The Snowman comes alive as a friendly golem and explores the house with the boy who built him, learning about light switches and playing dress up, before revealing that he can fly and whisking the child away to soar about the blanketed land.

So too do we own a 1988 edition of The Nutcracker that has become a favorite read beyond its season. It ends with the 12-year-old Clara waking from her dream of evil mice and brave toy soldiers, wherein the Nutcracker had transformed into a handsome prince and taken her on a sleigh ride to his winter castle. There, the two had danced at court until an ill wind blew and shadows blotted the light and the Nutcracker and his castle dissolved. After Clara wakes…

She went to the front door and peered into the night. Snow was falling in the streets of the village, but Clara didn’t see it. She was looking beyond to a land of dancers and white horses and a prince whose face glowed with love.

Since snow represents the dreamworld, sometimes it is a curse—like Narnia in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, wherein Father Christmas cannot enter when the witch’s magic holds, leaving only the negative element of winter. Snow’s semiotics is complex. We call it a “blanket of snow” because it is precisely like shaking out a blanket over a bed and letting it fall, and brings the same feelings of freshness and newness. But it can then be trammeled, and once so is irrecoverable. So snow is virginity, and snow is innocence. Snow is the end of seasons and life, but it is also about childhood.

It is especially about childhood because it only snows this much—as much as it snowed last night, and with such fluff and structure—for children. I mean that literally. I remember the great snows from my youth, when we had to dig trenches out to the barn like sappers and the edges curled above my head. I remember finding mountainous compacted piles left by plows with my friends, and we would lie on our backs and take turns kicking at a spot, hollowing a hole, until we had carved an entire igloo with just our furious little feet.

I did not think I would see snow this fluffy, this white, this perfectly deep, again in my life. I thought snow was always slightly disappointing, because it has been slightly disappointing for twenty-five years. Maybe that was a reality, or maybe snow had become an inconvenience. So I had accepted my memories of snow were like the memories of my childhood room, which keeps getting smaller on each return; so small, I feel, that the adult me can span all its floorboards in a single step.

Yet as I write this, I look outside, and there it is: the perfect snow. Just as it was, just as I remember it.

I understand now it can snow like this, and does snow like this, but only for children. And since I am back in a child’s story—albeit no longer as the protagonist—it can finally snow those snows of my youth once again.

Later today, we go out into the dreamworld.

Oh, you are already outside, I see.

You might be especially disheartened to learn that they are in fact taking away snow days. If more than one day they go to remote learning, in places like nyc I think they might even be doing remote learning on the very first snow day. In some places maybe 2nd grade and up, in some maybe K. Anyway, beautifully written!

You can’t mention The Snowman and not mention Walking in the Air:

https://music.youtube.com/watch?v=f0CLyDPY_U0&feature=shared