LK-99 as a cautionary tale for prediction markets

When "I like the stock" becomes "I like the rock"

“We are so back.”

That oft-repeated hopeful phrase defined online discourse late July and early August of 2023, after a paper by Korean authors was posted to arXiv, a pre-print server, claiming that a particular compound, LK-99, was a room-temperature superconductor. That video of a little rock floating briefly captured the attention of the globe.

Now, despite the initial enthusiasm, we know that we are not actually, as they say, back. Replication attempts show that LK-99 is almost certainly not a room-temperature superconductor. We are still. . . wherever we are. Somewhere not back.

Throughout the rise and fall of LK-99 as everyone awaited replication attempts (and the concomitant rise and fall of our dreams of infinite abundance), people turned to prediction markets to summarize the current chances of scientific replication. In fact, when I wrote about LK-99 in that month’s Desiderata, I too included an image from Manifold Markets of a market predicting whether or not LK-99’s claimed superconductivity would replicate.

The constant reference to prediction markets was understandable. Prediction markets have become quite popular, at least among the terminally online (I include myself in those afflicted) and its various pockets and communities. Talking about something abstract is made easier if there is a quantifiable market you can refer to (and some pretty graphs to post don’t hurt). In fact, prediction markets have been proposed as a way to grade the replication probabilities of scientific findings, exactly as they were supposed to be doing with LK-99. Some, like the polymathic Robin Hanson, have even proposed a “futarchy” wherein prediction markets replace, or at least supplement, the decision making of governments (others have argued for companies to do this as well). I know a number of people working in the prediction market space, and I think they are all well-meaning and smart. In fact, while writing this, I reached out with a question and the Manifold Markets team was quick to respond. I’ve even been kindly invited to the upcoming Manifest Conference on prediction markets, although I won’t be attending. Here’s what I would say there anyways:

To be truthful, when it came to LK-99, which seemed a tailor-made test for prediction markets, I thought they did a bad job (I’m not the only one). First, the probabilities never should have gotten as high as they did. As Nature points out:

Claims of room-temperature superconductors pop up regularly.

and these claims are, beyond being a dime a dozen, also are regularly retracted and notorious for being unreliable and reaching. Yet, the markets climbed to 60-70% certain that the superconductivity would replicate on most major prediction markets. This was despite there being nothing special about that particular superconductivity claim, in fact, it was by far not the strongest claim for superconductivity this year. E.g., just last March, there was another claim, this one peer-reviewed and published in the prestigious Nature by an American-lead team, of room-temperature superconductivity (the paper has turned out to have all sorts of problems in the data analysis). This should have been given a much higher chance of replicating than LK-99, and yet, even the very thinly-traded prediction markets of the time never treated it as having the same consistently high probability to replicate as the non-peer-reviewed pre-print by a relatively unknown team of authors.

So what was special about LK-99? Its virality. It’s not a perfect analogy, and the scale is far smaller, but there’s a sense in which LK-99 is much like the GameStop incident of 2021, wherein the online virality of a particular trade essentially broke the stock market (literally they stopped allowing the GameStop stock to be traded on exchanges), and it is not so far from “I like the stock” to “I like the rock.”

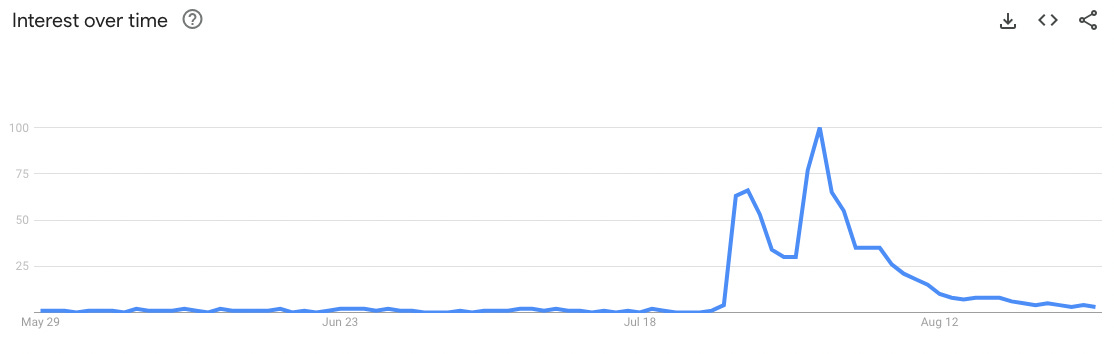

Compare, for instance, “superconductivity” as a Google trend vs. the actual prediction market probabilities for LK-99 turning out to be a real superconductor on Manifold Markets. Here’s Google trends:

While the x-axes of this and the graph below aren’t the same scale, if you look at the dates you’ll notice they match up; internet interest in LK-99 starts on the 25th of July, and there’s a further peak on August 1st. The exact same double-peak pattern plays out in the prediction market, on the same days.

Peak Google searches about the subject, and exactly when the markets reached close to 60-70% for the alleged superconductivity replicating, was August 1st. Everyone was talking about it.

The virality of LK-99 and its surge in the prediction markets tracked each other not just by the day, but by the hour. In fact, moments of Twitter virality appear to have driven the major spikes in the prediction markets.

For example, LK-99 rose to fame due to Alex Kaplan’s tweet on the 25th of July. Who’s Alex Kaplan? He currently runs a frozen coffee startup, but he also got an undergraduate degree in physics at Princeton, so it’s understandable why he was excited. The tweet now has 30 million views:

The same day, on Manifold a prediction market was opened and briefly spiked to almost 90% likelihood of superconductivity (perhaps due to low volume). However, after the markets settle for the next week, there’s a further spike up to 66% at 11 PM on July 31st.

What was happening at 11 PM, at literally the exact same time? Another viral tweet, this one at 10:52 PM, again sent by Alex Kaplan (who everyone had started following to keep track of the superconductor news—he gained tens of thousands of followers). The 10:52 PM tweet pointed to another arXiv pre-print, this one claiming to establish a theoretical basis for the proposed superconductivity.

The “This is huge” tweet went viral to the tune of millions of views, and the predicted probability of superconductivity immediately peaked. How many people who could actually understand the linked paper itself were betting in the prediction markets? My guess is effectively zero. They saw the tweet as it went viral and bet accordingly.

Even though my scientific research sometimes touches on the subject when discussing emergence or consciousness, I’m not a physicist, and so my knowledge of superconductivity is probably similar to most people—I have a passing familiarity. I looked into this timeline because the markets reflected almost exactly the social media posts I (and everyone else) was reading, not the experts who were mostly counseling caution. So as a finger on the pulse of the online conversation, as an “excitement barometer,” the prediction markets did a good job when it came to LK-99. Yet surely the point of a prediction market is, well, prediction, not just to be a mere reflection of what’s trending on social media?

Perhaps this isn’t surprising. Speculative markets, those which are unconnected to any agreed-upon fundamental valuations, are prone to wild swings and expansive valuations. See, e.g., Tesla’s skyrocketing valuation in the early 2020s, eventually reaching a valuation wherein it would have to eat the majority of the global EV car market to support it. According to Forbes back in 2021:

Tesla’s (TSLA) market cap surpassed the trillion-dollar mark. . . Put another way, the $1.2 trillion valuation implies Tesla owns 60%+ of the entire global passenger EV market and becomes more profitable than Apple (AAPL) by 2030.

The reason for the unconnected-to-reality valuation of Tesla is that tech companies are closer to being a speculative market than car companies, and Tesla was being treated like a tech company rather than a car company.

Of course, all markets behave wildly, and have their inefficiencies, but the more speculative a market, the more prone it is to these things. Think back to the 2017 cryptocurrency market. As I wrote then:

For those who weren’t paying attention to the insanity that was the 2017 cryptocurrency market, consider how amazing it is that during any particular day in 2017—it could be a day without any remarkable weather; unmemorable in every other conceivable way — there were people making and losing fortunes, experiencing agony and ecstasy, all through the portals of their screens. What were normal days for you might have been heaven or hell for them.

Personally, I still think Bitcoin and Ethereum are both technologically and also philosophically very promising, and I think crypto is going to be a major 21st century market. But detached from anything but hype, the more people entered the market the crazier it got. The scams intensified as the money got funny. The New York Times ran an article with this incredible headline:

If you were in the cryptocurrency market at the time, what you quickly learned was that the easiest path to funny money was not some fundamental analysis of the underlying currencies and their technology and choosing the best, like you were some Warren Buffet of decentralization. Instead it was much more profitable to simply bet on the exuberance of the crowd as it discovered new thinly-traded coins to promote (colloquially called “shit coins”).

While I doubt that prediction markets will ever reach the popularity of cryptocurrency, it seems a problem to me that speculative markets are always the worst kinds of markets, the most susceptible to hype, and LK-99 seems to be an early indicator that hype, not rationality, can easily dominate prediction markets.

I’m aware, of course, that the near tautological power of markets can always be appealed to. If prediction markets were too speculative and too virality-based, then wouldn’t experts stand to make a killing in the prediction markets by betting against such things? Perhaps. For experts are drops in the bucket, and prediction markets can stay irrational much longer than a small number of experts can stay solvent.

My point is not that prediction markets don’t ever work, that they’re stupid, or that they’re not worth pursuing. In fact, I’m open to them being legal, instead of existing in this weird gray zone and currently being mostly limited to play money. But after watching closely how they behaved with LK-99 I’m now more skeptical that something so entangled with the very subject it is supposed to be predicting, and dealing with such complex real-world issues, will not be disappointingly less predictive than it is merely reactive and reflective.

Perhaps these problems are ephemeral byproducts of the markets being low-volume and constructed with play money? That could be the case. But I have a feeling the problem is more fundamental. In a sense, prediction markets are never about what they’re predicting. Any initial setup of a true or false prediction when a market is established is quickly replaced with the classic buy-low sell-high dynamics that constitutes success in markets, and it is there, in the shifts and madnesses, that the most money can be made. It’s better to bet on hype than the right answer. This inescapable shift in target from what you predict will happen to guessing what everyone else will predict will happen seems similar as a meta-problem to Goodhart’s law: “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Meanwhile, the influence of virality on prediction markets looks impossible to avoid, since the volume of any given prediction market will be extremely sensitive to what is trending online, and the necessity and ability to constantly create new markets (as more events to predict crop up) means that most prediction markets will be low volume anyways, since there will be so many of them. Note that this ability to spin up additional speculative low-volume markets on demand looks almost exactly like how people would find or invent new small market cap cryptocurrencies to promote, and most of these ended up as scams (even if they weren’t purposeful ones), in that they were little more than white papers and a lifeless token to trade on the Ethereum network. Right now cryptocurrency is a trillion dollar market, and it would be a dream success for prediction markets if they ever eventually achieved similar volume. Yet, even with a sector market cap in the trillions, there are 10,000 different cryptocurrency markets listed on coinmarketcap.com, and most of those are barely traded pump-and-dump scams. So if prediction markets were ever legalized and serious money poured in, I’d worry that the same behaviors would occur, just as they did in cryptocurrency, but perhaps even worse.

I don’t say this as a worrying pearl-clutcher—I say that as someone who likes crypto but also thinks all those low-market-cap scam coins made crypto as a whole significantly worse. Like almost ruining it completely. And personally, I think people have a responsibility over their own investments, and if people want to lose their savings (or bet big and occasionally win), they should be able to in most cases. I’m firmly against, e.g., the idea of accredited investors as being special and possessing better judgement just because they have a million dollars in the bank. Still. Having now seen prediction markets in action on LK-99, I think they are good at acting as de-facto very fast public polls (of the very online), but I’m worried that they don’t have much actionable soothsaying information above-and-beyond reflecting enthusiasm, and it’s unclear to me (a) how to avoid this, and also (b) what they would even look like at scale, other than similar to crypto, but potentially worse.

If the usefulness of prediction markets that everyone is after is merely to responsively jump to the tune of online opinion, then they do a pretty good job, even now just with play money. I definitely think that this use, much like polling, is important, and can be a useful index to key off of. Such markets are, in a way, the perfect blessing for commentators such as myself, reifying the abstract by providing pretty pictures and numbers to fuss over. But to become more enthusiastic about the idea as the panacea it’s sometimes presented as I’d like to see prediction markets do more than just track viral tweets.

I’m skeptical of prediction markets because of this paradox (or at least perceived paradox):

For markets to work, there needs to be enough people participating. But there isn’t much incentive to participate, because we expect the probability to reflect the actual probability of the outcome, and therefore there is no money to be made. In the stock market, there is always incentive to participate, even when the stock is a true reflection of the company value, because the value of the company grows (on average). It is this cooperation of incentives that makes the stock market work, and it doesn’t exist in prediction markets. You are only incentivized to participate if you think the market is wrong. This will either be an extremely small number of (mistaken; therefore eliminating all incentive) people or the market will just not be a reflection of the true probability. I just don’t see the market effects kicking in.

This is not meant as condescending. It is a possible explanation of the deviation we see in prediction markets. They are quite good at prediction the sports playoffs. A good quarterback or array of pitchers on a given team is not opaque. Prediction markets are a fun analog for perceived understanding.

Many years ago I was doing work in the control and monitoring markets for nuclear power. An intelligent colleague back in the day shared a perspective I have never forgotten and believe it applies. He explained way back then why nuclear generation COULD NEVER SUCCEED broadly. It had NOTHING to do with the approach, it had to do with the degree of broad understanding. The creators and managers of finance and books are stuck in a region of MODEST understanding. It is likely they achieved their lot in life without much of an understanding of mathematics beyond the basics. Supply and demand curves are important but are dumbed down representations of reality. A person can probably be a "star" or "creator" and not have a firm grasp of even calculus. Being able to turn a phrase to effect opinion is a different sort of gift.

My colleague observed that ANYTHING we do societally that is based upon even modest complexity will always be speculative, never understood, easily manipulable, and hence feared. It's broad success will be undermined unless broad education were to change. This is why power generated by fission is doomed with the broader public. People just don't really know what a neutron is. We need Michael Lewis to explain it or some writer of a Newsletter. As for conductivity, while people have some grasp of what temperature and pressure are, I would surmise that <<1% of the population knows what conductivity even means!!! Sometimes when I share the old sop "a pint's a pound the world around" I am amazed that people don't even have a general sense of mass and volume. To expect them to translate their Meta/Twitter feelings (mostly based on who they follow) into meaningful predictions or sensibility about something they are in the dark about can only end badly. Their predictions are hence based on nothing more than the "wisdom of the crowd" -- any one they self-select perhaps by experience or taste in clothing. The closest finance has gotten to madness in the markets was flash trading and derivatives. Only Michael Lewis managed the trick or explaining their underlying basis. Our modern world is finally advancing in more realms exponentially. I fear the average person is not firmly comfortable with logarithms.

All of this is a longhand explanation of why imagining early clicking in a predictions / futures market on ANYTHING OF MODEST SCIENTIFIC COMPLEXITY is like betting green on the roulette wheel or who will win the coin flip at the SuperBowl. It is fun, it is harmless, it is NOT predictive. The more complex the concept, the more settling time required before behavior is sensible to even pay attention to.