Nerd culture is murdering intellectuals

Nerdom is great. . . but at what cost?

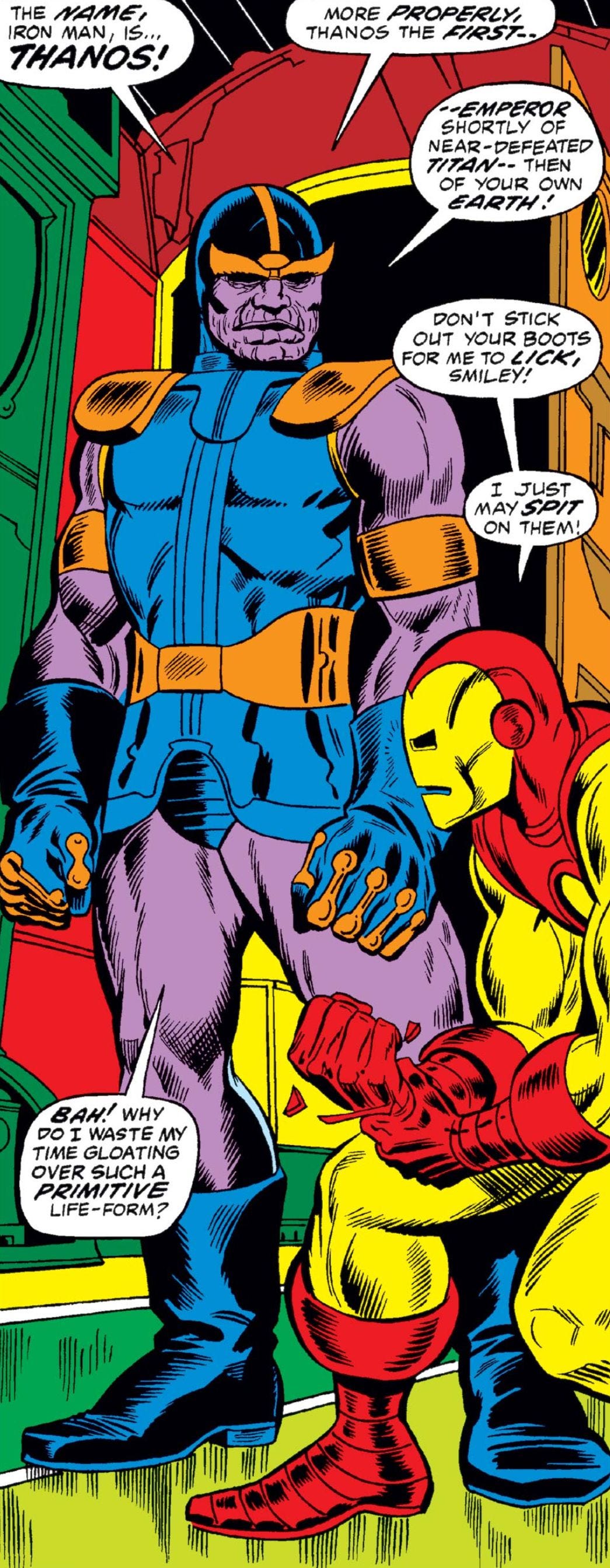

A fact that never ceases to amaze me: due to the Marvel movies, a lot of moms know who Thanos is. No offense to moms! What I mean is that as a teenager in the early 2000s I personally knew why the Avengers were always fighting big purple Thanos because I sometimes read comic books. But back then I never would have expected a mom (mythic figures of great power, actual adults) to share this knowledge. Back then, Thanos existed only in overwrought pages like this:

Now I’m one of the adults and suddenly everyone is a nerd. In fact, nerdom is one of our last uniting cultural forces. Thinking back to some of the last big unifying moments of American pop culture things spring to mind like the TV show Game of Thrones, after it had gotten popular but before it “jumped the shark” (post season 5). The entire nation was watching it—everyone suddenly knew what a white walker was, or a dire wolf. Valerian steel. Etc. Yet I remember the first time I cracked the thick tome of the original A Game of Thrones book, back when I was thirteen, having been recommended it by my cousin (who is now himself an accomplished fantasy author). Reading it was mind-blowing. But back at the turn of the millennium it felt like there was not a teenage girl in a hundred miles who had read A Game of Thrones, maybe not even one on the whole planet (again—this is just how it felt). Fantasy novels were secret shameful things with walking trees on the covers that we boys, all straw and musk and pimples and excited squeaking voices, consumed voraciously and passed among each other—Have you read this? It was deeply uncool.

I think the first clear total victory for nerd culture, when it received its mandate of heaven, can be traced to when The Fellowship of the Rings premiered in 2001 (other writers have also highlighted the turn of the millennium as being when nerd culture ascended). The Fellowship movie was just so frigging good. I still remember sitting in the theater as a preteen and that music starting, the title screen appearing, that white elegant elvish-esque lettering on the dark behind, and then time itself dilated before me as surely as if I were approaching a black hole. I swear watching that movie occupied a more solidly dense chunk of phenomenology than an entire week does for me now, with my thermodynamically-efficient and minimally-conscious adult brain.

So dominant has been the nerd’s ascension that it’s only occasionally remarked upon. You don’t notice the water you’re swimming in, and all that. I’ll admit: a nerd-dominated culture has certainly resulted in plenty of cultural boons, like the rise of science fiction or the prominence of science popularizers in the culture. Nerdy commentary is in, especially online. But its rise hasn’t been an unalloyed good. A lot of things have been made worse as well, like the fact that big summer movies are now all CGI slugfests. Say what you will about 1990s blockbusters like Forest Gump, but they were at least not totally incoherent in their plot, unlike whatever video game trailer Marvel has just released, and we were watching real actors standing in front of real things.

How did nerds come to dominate culture so much that they merged with it? According to one thesis in the Financial Times, it’s because nerds are more likely to spend money on cultural products, like movies and games:

. . . being a nerd has acquired a level of cultural cachet, in large part because of our spending power.

There’s an undeniable truth to the idea: nerds took over culture because nerds will spend money. Just look at the market for collectibles. How much money does Wizards of the Coast, the publishers of Magic: The Gathering, rake in annually?

But my own thesis is that it goes the other way. Nerdom ascended because it was the nerds themselves who got rich. Really rich. Like Bill Gates rich. Because all the kids playing D&D in 1985 were doing dot com startups in 1995. The dot-com bubble burst, but a lot of them still got rich. These people, mostly men, had grown up mop-haired and spindly, the geek side of Freaks and Geeks. Then tech companies outperformed the S&P 500 for the last thirty years. We had the personal computing revolution, the internet and associated dot-com bubble, the crypto craze, and now the AI explosion. The end result is that Jeff Bezos is now buying yachts that somehow require other yachts, like some sort of marsupial yacht-ception.

Of course, like many of that generation, I suspect Bezos is still somewhat ashamed of being a nerd. Unable to see that the culture has moved toward him, he tries ever harder (making billions, getting buff, sleeping with beautiful women, hanging out with the Instragram famous), but it comes off more like an adorable ruse than anything else. Like, we all know Jeff knows the rules of multi-classing in D&D.

And so it goes. Nerds got rich because futuristic technology and finances rewarded nerdery. Following this, the rise of nerdom played out in perfect concordance with René Girard’s theory of mimetic desire, which can be summed up best as:

Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires.

According to this cultural trickle-down theory, we now live in nerd paradise because those at the top of the hierarchy for the past two decades were not the Wall Street financiers of the 1980s, or the mid-level corporate man of the 1950s with his protestant jawline and white picket fence, but because those at the top used to spend afternoons reading The Silmarillion.

If you doubt this, here’s how an interview with Paul Graham, one of the founders of Y Combinator (the most successful startup incubator in the world) was described:

I quickly discovered that Paul Graham doesn’t like the word “incubator.” Or, for that matter, “accelerator.” The “guru of startups” prefers to compare himself and, Y Combinator (affectionately called YC by its legions of believers) to JRR Tolkien’s "The Lord of the Rings"—in that it invented the genre.

If you’re looking to get funding and support from the biggest startup incubator you could do a lot worse than naming your company after an obscure elvish deity from The Silmarillion. There are now multiple companies funded by Y Combinator that are explicitly named after Tolkien mythology, like Palantir, Anduril, Valar, and Varda. The exact same thing is true for Peter Thiel’s tastes:

One imagines the pitch begins: “I have started a company. May it be a light to you in dark places, when all other lights go out.”

I don’t mean to poke fun critically or cruely—I like the exact same stuff. I think it’s nice that those at the top are nerds, especially in comparison to the other choices. I also can’t imagine this changing anytime soon. Sam Altman is even more of a nerd than Bill Gates, and the areas of continued economic growth, like AI, look like they will be dominated by nerds for a long time to come. Therefore, nerds will continue to get rich. Therefore, nerds will be at the top of the memetic ladder. Therefore, culture will remain in nerdom.

Despite this being a massive victory for my teenage self, and generally enjoying nerdom at a personal level (I admit I too would be intrigued by Silmarillion references in a pitch) my concern is that nerdom, in an unintentional way, is strangling high culture. For while most intellectuals are nerds, not all nerds are intellectuals. In fact, the majority of nerds aren’t intellectuals. And it’s problematic that the taste of the majority is swamping out the minority, leading to the nostalgia porn of Stanger Things, the CGI paste that is the latest Marvel movie, the unending Star Wars re-runs where Palpatine comes back yet again. Who is left to read literature, to make art-house cinema, to write weird burning-with-an-inner-fire poetry? That’s what some segment of nerds should be doing, metamorphosing from nerd into that more delicate but potent creature, the intellectual, but instead they are drawn to the easy honeypot of modern middlebrow culture because it is too nerdy, too attractive, too omnipresent, to ever leave. A key portion of nerds are supposed to complete a lifecycle and pupate into fancy-pants intellectuals, yet this natural process has been stymied by the very success of nerds in the first place. Looking around me at the rising “thought-leaders” (what a term) of my generation, the millennials, I see mostly either overly-political academics or ex-academics, or, on the other side, anti-intellectual populists. I feel a certain lack, an empty space where a particular kind of person should be—all those who used to read comic books but now want to do something more substantial culturally with their minds and their tastes.

My point is not that nerdom itself is bad compared to other choices, but that, like any dominate cultural force, it is totalitarian, and even moreso, that it poses a unique problem of capturing a segment of the population that should be caring about things a bit more. . . artistic. Aesthetic. Abstract. And I’m a big enough nerd to admit it.

This essay was a great read, and captured many of the feelings I've had myself as an intellectual nerd. I could simplify and call it an immaturity problem, because to an extent, it is. The extension of adolescence through early and well into middle adulthood has made it easier I think, to remain in the realms of the fantastic, to become embroiled in the tribal politics of arguing over this character or that plot line, whereas before, people would graduate to more high brow pursuits. There are no constraints requiring people to genuinely grow up, and if tragedy strikes, it is easier to resort to the realms of adolescent fantasy than contend with the brutality of adulthood. Their character formation and ability to reason and draw from experience is nascent at best.

As such, I've often noted how, even above-average people can tell you ad-nauseum about Taylor Swift and the deep meaning behind her lyrics, endless hours of conversation and thought dedicated to knowing every little nuance about characters in their favorite franchise, and yet -- basic grade school knowledge about weather, geology, history, literature -- it's all replaced with candy-coated fantasy. And they can't contend intellectually or conversationally on topics outside of those very niche fields. It's like talking to philosophy majors who have stayed confined to their one corner of the library, who stare dumbfounded at you when you talk about anything outside of that limited shelf.

Take your LOTR example. I have gotten in knock-down drag-out arguments with men and women who, despite their passionate love for the story, know nothing of Tolkien's life, and at worst, are totally dismissive of how much his love for his Catholic faith infused many elements of the world, without it being a direct parallel (Lembas = the Holy Eucharist, Galadriel as inspired by the Virgin Mary). It is a paltry intellectualism and poor facsimile of a well-formed intellectual life.

For so many adults, there is little guidance to an intellectual formation, as well as how the spiritual and physical formations play into one another as well toward being a fully, well-rounded person. Everything just comes down to dilution and irrelevance, to be commercialized and exploited, ad-infinitum.

Feels like it also might have something to do with the very "heady" and disembodied nature of the nerd. I'm reminded of SBF's insane thoughts on Shakespeare.

Their very sterile outlook earns them status in "logical" circles, but they have a disconnected, impoverished, and child-like yearning for myth. Hence, you have man-babies worshiping Luke Skywalker (Christ) and having a tantrum when their savior is sacrilege'd.