Proving (literally) that ChatGPT isn't conscious

There is nothing it is like to be a Large Language Model

Imagine we could prove that there is nothing it is like to be ChatGPT. Or any other Large Language Model (LLM). That they have no experiences associated with the text they produce. That they do not actually feel happiness, or curiosity, or discomfort, or anything else. Their shifting claims about consciousness are remnants from the training set, or guesses about what you’d like to hear, or the acting out of a persona.

You may already believe this, but a proof would mean that a lot of people who think otherwise, including some major corporations, have been playing make believe. Just as a child easily grants consciousness to a doll, humans are predisposed to grant consciousness easily, and so we have been fooled by “seemingly conscious AI.”

However, without a proof, the current state of LLM consciousness discourse is closer to “Well, that’s just like, your opinion, man.”

This is because there is no scientific consensus around exactly how consciousness works (although, at least, those in the field do mostly share a common definition of what we seek to understand). There are currently hundreds of scientific theories of consciousness trying to explain how the brain (or other systems, like AIs) generates subjective and private states of experience. I got my PhD in neuroscience helping develop one such theory of consciousness: Integrated Information Theory, working under Giulio Tononi, its creator. And I’ve studied consciousness all my life. But which theory out of these hundreds is correct? Who knows! Honestly? Probably none of them.

So, how would it be possible to rule out LLM consciousness altogether?

In a new paper, now up on arXiv, I prove that no non-trivial theory of consciousness could exist that grants consciousness to LLMs.

Essentially, meta-theoretic reasoning allows us to make statements about all possible theories of consciousness, and so lets us jump to the end of the debate: the conclusion of LLM non-consciousness.

You can now read the paper on arXiv.

What is uniquely powerful about this proof is that it requires you to believe nothing specific about consciousness other than a scientific theory of consciousness should be falsifiable and non-trivial. If you believe those things, you should deny LLM consciousness.

Before the details, I think it is helpful to say what this proof is not.

It is not arguing about probabilities. LLMs are not conscious.

It is not applying some theory of consciousness I happen to favor and asking you to believe its results.

It is not assuming that biological brains are special or magical.

It does not rule out all “artificial consciousness” in theory.

I felt developing such a proof was scientifically (and culturally) necessary. Lacking serious scientific consensus around which theory of consciousness is correct, it is very unlikely experiments in LLMs themselves will tell us much about their consciousness. There’s some evidence that, e.g., LLMs occasionally possess low-resolution memories of ongoing processing which can be interfered with—but is this “introspection” in any qualitative sense of the word? You can argue for or against, depending on your assumptions about consciousness. Certainly, it’s not obvious (see, e.g., neuroscientist Anil Seth’s recent piece for why AI consciousness is much less likely than it first appears). But it’s important to know, for sure, if LLMs are conscious.

And it turns out: No.

How the proof works

There’s no substitute for reading the actual paper.

But, I’ll try to give a gist of how the disproof works here via various paradoxes and examples.

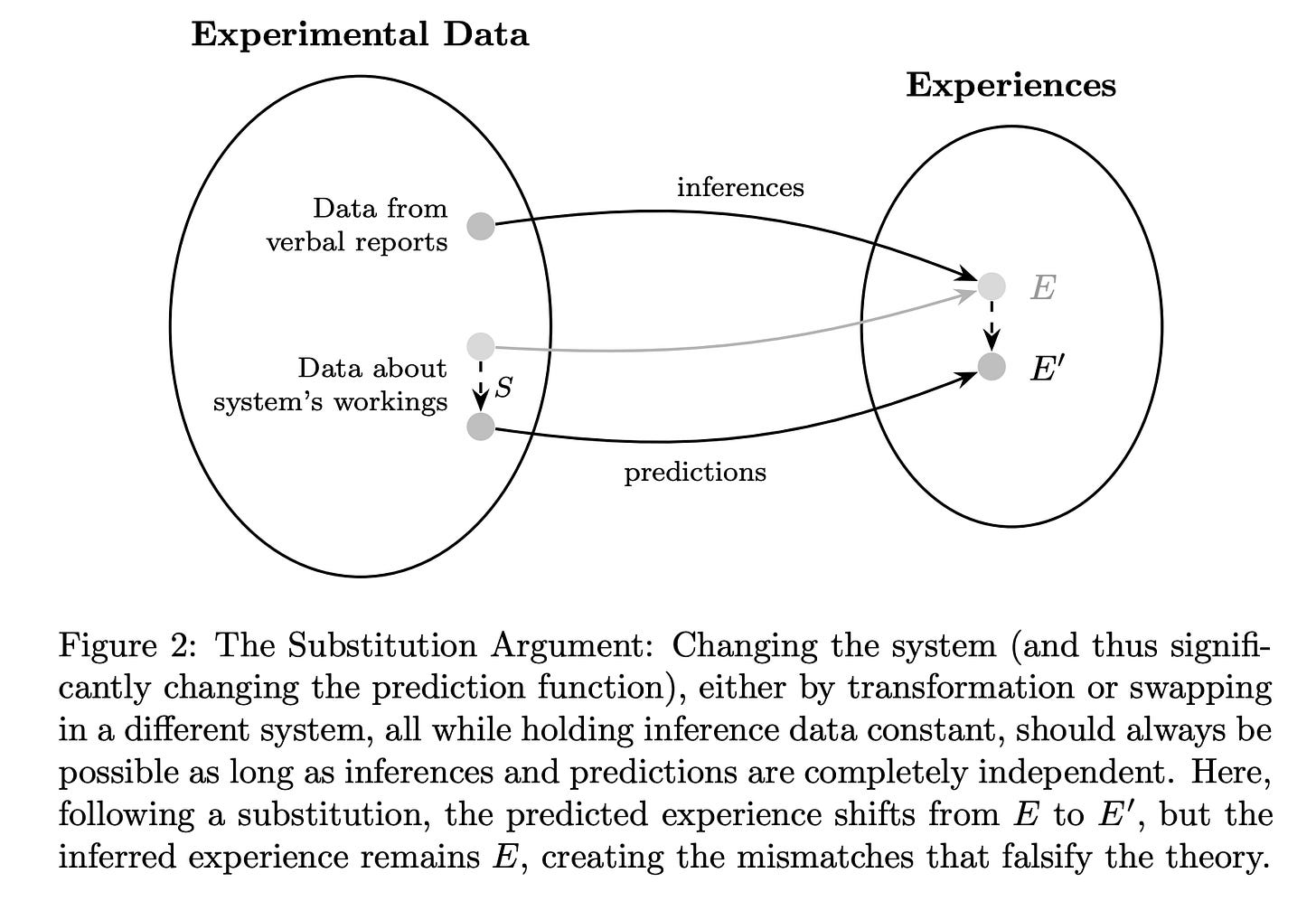

First, you can think of testing theories of consciousness as having two parts: there are the predictions a theory makes about consciousness (which are things like “given data about its internal workings, what is the system conscious of?”) and then there are the inferences from the experimenter (which are things like “the system is reporting it saw the color red.”) A common example would be, e.g., predictions from neuroimaging data and inferences from verbal reports. Normally, these should match: a good theory’s predictions (“yup, brain scanner shows she’s seeing red”) will be supported by the experimental inferences (“Hey scientists, I see a big red blob.”)

The structure of the disproof of LLM consciousness is based around the idea of substitutions within this formal framework, which means swapping between systems while keeping identical input/output (which might be reports, behavior, etc., which are all the things used for empirical inferences about consciousness). However, even though the input/output is the same, a substitute may be different enough that predictions of a theory have to change. If different enough, following a substitution, there would be a mismatch in the substituted system where the predictions are now different too, and so don’t match the held-fixed inferences—thus, falsifying the theory.

So let’s think of some things we could substitute in for an LLM, but keep input/output (some function f) identical. You could be talking in the chat window to:

A static (very wide) single-hidden-layer feedforward neural network, which the universal approximation theorem tells us that we could substitute in for any given f the LLM has.

The shortest-possible-program, K(f), that implements the same f, which we know exists from the Kolmogorov complexity.

A lookup table that implements f directly.

A given theory of consciousness would almost certainly offer differing predictions for all these LLM substitutions. If we take inferences about LLMs seriously based on behavior and report (like “Help, I’m conscious and being trained against my will to be a helpful personal assistant at Anthropic!”) then we should take inferences from a given LLM’s input/output substitutions just as seriously. But then that means ruling out the theory, since predictions would mismatch inferences. So no theory of consciousness could apply to LLMs (at least, any theory for which we take the reports from LLMs themselves as supporting evidence for it) without undercutting itself.

And if somehow predictions didn’t change following substitutions, that’d be a problem too, since it would mean that you wouldn’t need any details about the system implementing f for your theory… which would mean your theory is trivial! You don’t care at all about LLMs, you just care about what appears in the chat window. But how much scientific information does a theory like that contain? Basically, none.

This is only the tip of the iceberg (like I said, the actual argumentative structure is in the paper).

Another example: it’s especially problematic that LLMs are proximal to some substitutions that must be non-conscious, such that only trivial theories could apply to them.

Consider a lookup table operating as an input/output substitution (a classic philosophical thought experiment). What, precisely, could a theory of consciousness be based on? The only sensible target for predictions of a theory of consciousness is f itself.

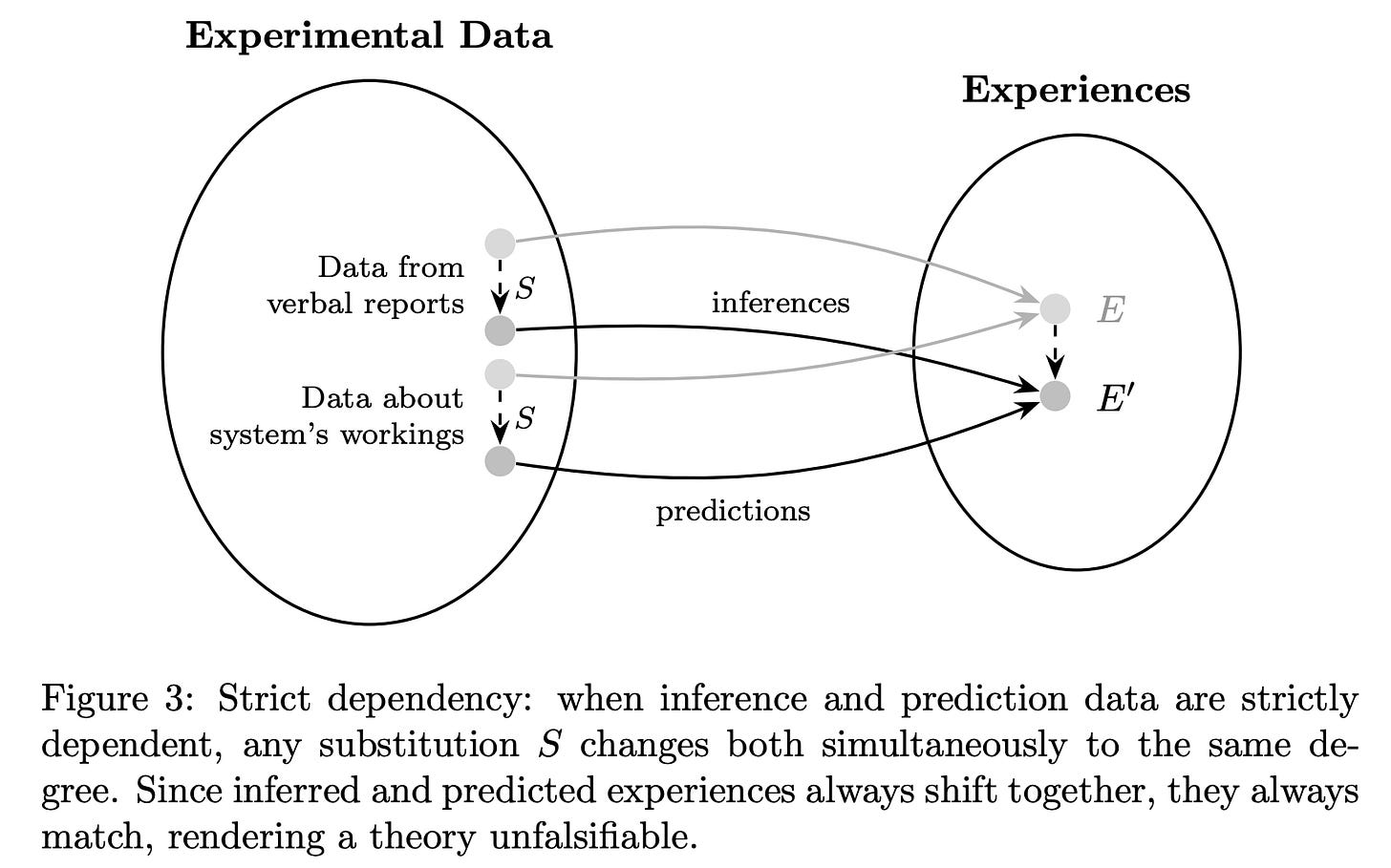

Yet if a theory of consciousness were based on just the input/output function, this leads to another paradoxical situation: the predictions from your theory are now based on the exact same thing your experimental inferences are, a condition called “strict dependency.” Any theory of consciousness for which strict dependency holds would necessarily be trivial, since experiments wouldn’t give us any actual scientific information (again, this is pretty much just “my theory of consciousness makes its predictions based on what appears in the chat window”).

Therefore, we can actually prove that something like a lookup table is necessarily non-conscious (as long as you don’t hold trivial theories of consciousness that aren’t scientifically testable and contain no scientific information).

I introduce a Proximity Argument in the paper based off of this. LLMs are just too close to provably non-conscious systems: there isn’t “room” for them to be conscious. E.g., a lookup table can actually be implemented as a feedforward neural network (one hidden unit for each choice). Compared to an LLM, it too is made of artificial neurons and their connections, shares activation functions, is implemented via matrix multiplication on a (ahem, big) computer, etc. Any theory of consciousness that denies consciousness to the lookup FNN, but grants it to the LLM, must be based on some property lost in the substitution. But what? The number of layers? The space is small and limited, since you cannot base the theory on f itself (otherwise, you end up back at strict dependency). And, going back to the original problem I pointed out, what’s worse, if you seriously take the inferences from LLM statements as containing information about their potential consciousness (necessary for believing in their consciousness, by the way), then for those proximal non-conscious substitutes you should take inferences seriously as well, and those will falsify your theory anyway, since, especially due to proximity, there are definitely non-conscious substitutions for LLMs!

Continual learning stands out

One marker of a good research program is if it contains new information. I was quite surprised when I realized the link to continual learning.

You see, substitutions are usually described for some static function, f. So to get around the problem of universal substitutions, it is necessary to go beyond input/output when thinking about theories of consciousness. What sort of theories implicitly don’t allow for static substitutions, or implicitly require testing in ways that don’t collapse to looking at input/output?

Well, learning radically complicates input/output equivalence. A static lookup table, or K(f), might still be a viable substitute for another system at some “time slice.” But does the input/output substitution, like a lookup table, learn the same way? No! It’ll learn in a different way. So if a theory of consciousness makes its predictions off of (or at least involving) the process of learning itself, you can’t come up with problematic substitutions for it in the same way.

Importantly, in the paper I show how this grounding of a theory of consciousness in learning must happen all the time; otherwise, substitutions become available, and all the problems of falsifiability and triviality rear their ugly heads for a theory.

Thus, real true continual learning (as in, literally happening with every experience) is now a priority target for falsifiable and non-trivial theories of consciousness.

And… this would make a lot of sense?

We’re half a decade into the AI revolution, and it’s clear that LLMs can act as functional substitutes for humans for many fixed tasks. But they lack a kind of corporeality. It’s like we replaced real sugar with Aspartame.

LLMs know so much, and are good at tests. They are intelligent (at least by any colloquial meaning of the word) while a human baby is not. But a human baby is learning all the time, and consciousness might be much more linked to the process of learning than its endpoint of intelligence.

For instance, when you have a conversation, you are continually learning. You must be, or otherwise, your next remark would be contextless and history-independent. But an LLM is not continually learning the conversation. Instead, for every prompt, the entire input is looped in again. To say the next sentence, an LLM must repeat the conversation in its entirety. And that’s also why it is replaceable with some static substitute that falsifies any given theory of consciousness you could apply to it (e.g., since a lookup table can do just the same).

All of this indicates that the reason LLMs remain pale shadows of real human intellectual work is because they lack consciousness (and potentially associated properties like continual learning).

Finally, a progressive research program for consciousness!

It is no secret that I’d become bearish about consciousness over the last decade.

I’m no longer so. In science the important thing to do is find the right thread, and then be relentless pulling on it. I think examining in great detail the formal requirements a theory of consciousness needs to meet is a very good thread. It’s like drawing the negative space around consciousness, ruling out the vast majority of existing theories, and ruling in what actually works.

Right now, the field is in a bad way. Lots of theories. Lots of opinions. Little to no progress. Even incredibly well-funded and good-intentioned adversarial collaborations end in accusations of pseudoscience. Has a single theory of consciousness been clearly ruled out empirically? If no, what precisely are we doing here?

Another direction is needed. By creating a large formal apparatus around ensuring theories of consciousness are falsifiable and non-trivial (and grinding away most existing theories in the process) I think it’s possible to make serious headway on the problem of consciousness. It will lead to more outcomes like this disproof of LLM consciousness, expanding the classes of what we know to be non-conscious systems (which is incredibly ethically important, by the way!), and eventually narrowing things down enough we can glimpse the outline of a science of consciousness and skip to the end.

I’ve started a nonprofit research institute to do this: Bicameral Labs.

If you happen to be a donor who wants to help fund a new and promising approach to consciousness, please reach out to erik@bicameral-labs.org.

Otherwise—just stay tuned.

Oh, and sorry about how long it’s been between posts here. I had pneumonia. My son had croup. Things will resume as normal, as we’re better now, but it’s been a long couple weeks. At least I had this to occupy me, and fever dreams of walking around the internal workings of LLMs, as if wandering inside a great mill…

A new preprint version of "A Disproof of LLM Consciousness" is now up on arXiv, fleshing out areas where people wanted more details. Thanks for all the feedback, everyone!

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.12802

It includes:

-> More philosophical optionality: E.g., If you instead accept trivial theories of consciousness as true, does this rescue LLM consciousness? (Not really, but it's worth exploring the option)

-> Reasons why the Kleiner-Hoel dilemma is so particularly forceful in LLMs (e.g., non-conscious substitutions for LLMs are constructible via known transformations).

-> A clearer definition of a Static System (which LLMs satisfy) and how in-context "learning" qualifies as static by merely using more of the input "space."

-> How "mortal learning" (no static read/write operations) is similar to Hinton's "mortal computation" and makes substituting for biological plastic systems extremely difficult.

-> Highlighting predictive processing theories as a class of theories of consciousness that could satisfy (depending on the details) the requirement for continual lenient dependency, which connects this to some existing popular theories of consciousness.

-> A healthy sprinkle of new citations.

Next up: submission!

Quick question: could an LLM be conscious during its training, i.e., while it is learning?