Jim Simons—former professor who made contributions to the math behind string theory, turned arguably the most successful “quant” in finance ever, turned billionaire philanthropist—died on Friday, at the age of 86. I knew of Jim Simons because he funded a great deal of science behind the scenes, and tales of him by fellow scientists were usually accompanied by some funny story of his larger-than-life personality (like his penchant for smoking cigars inside). If you want to read a normal obituary, you can check out The New York Times. What follows is an abnormal obituary. For I personally met Jim only once, but it was in a manner, I believe, of the classic archetypal case.

I had applied to be a Simons Fellow: a program in New York that gives you three years to just research whatever you like, free of teaching or administrative duties. A bunch of us promising younglings had made it to the interview stage and therefore through the doors and greenery and water features of the Flatiron Institute in downtown Manhattan. We would give interviews and then listen to a talk. Rumor had it Jim himself would be there, for it was the location of the Simons Foundation.

The interviews were, at least for me, an utter disaster. I remember walking into the small room with an already-crowded whiteboard and three prominent professors of neuroscience, the names of whom I recognized. I presented my mathematical theory of emergence and its relevancy to understanding cortical function. They barely looked up from their keyboards, clacking away at emails as I spoke. Zero eye contact. Judging the applicants for the fellowship program was obviously just another day-to-day bureaucratic on-going for them. At the time (in my twenties) I remember day-dreaming (in the way only an idealistic young scientist would) that maybe Jim Simons would walk by, see something interesting on the whiteboard, and pop his head in, overriding people who seemed to me, once viewed in the flesh, as disappointingly little more than middle management gatekeepers. After the dismal show of interest, I left 100% sure I wouldn’t become a Simons Fellow.

Later, I think it was Simon DeDeo who presented a talk to all of us, including Jim, on the fall of complexity in poetry. It turns out that if you measure the entropy of published poems they’ve been declining as far back as back goes. It was the kind of thing that seemed right at home in the institute—perhaps everyone was getting increasingly stupid, and only the few brightest found ways to win out. Jim, of course, fell asleep in the front row. Human memory is a fallible thing, so susceptible to expectation, but in my memory after the talk, while everyone broke into sparse huddles like they usually do after something thought-provoking, I could have sworn Jim lit up his cigar inside the building, his building—this is in like 2018—and calmly kept talking while puffing in the face of his interlocutor.

I really appreciated that. It reminded me of a professor I once had, an old-school biologist, one who shared the same white hair and grumbling voice as Jim, along with the same penchant for cigars. He (the biologist) was the kind to laugh at our squeamishness in the wet lab over measly things like carcinogens, which he was known to mouth pipette. He brewed beer in the basement and gave it to us after challenging classes and didn’t ask questions about age. He too was intellectually active into his 80s, still robust, still contributing. The kind of man who didn’t treasure his body in the effete way elites do now, so afraid to smoke, so afraid to drink, so afraid of not taking the right supplements. The older class both men belonged to viewed the body as a thing to be used up, and used up well, by the end of it all.

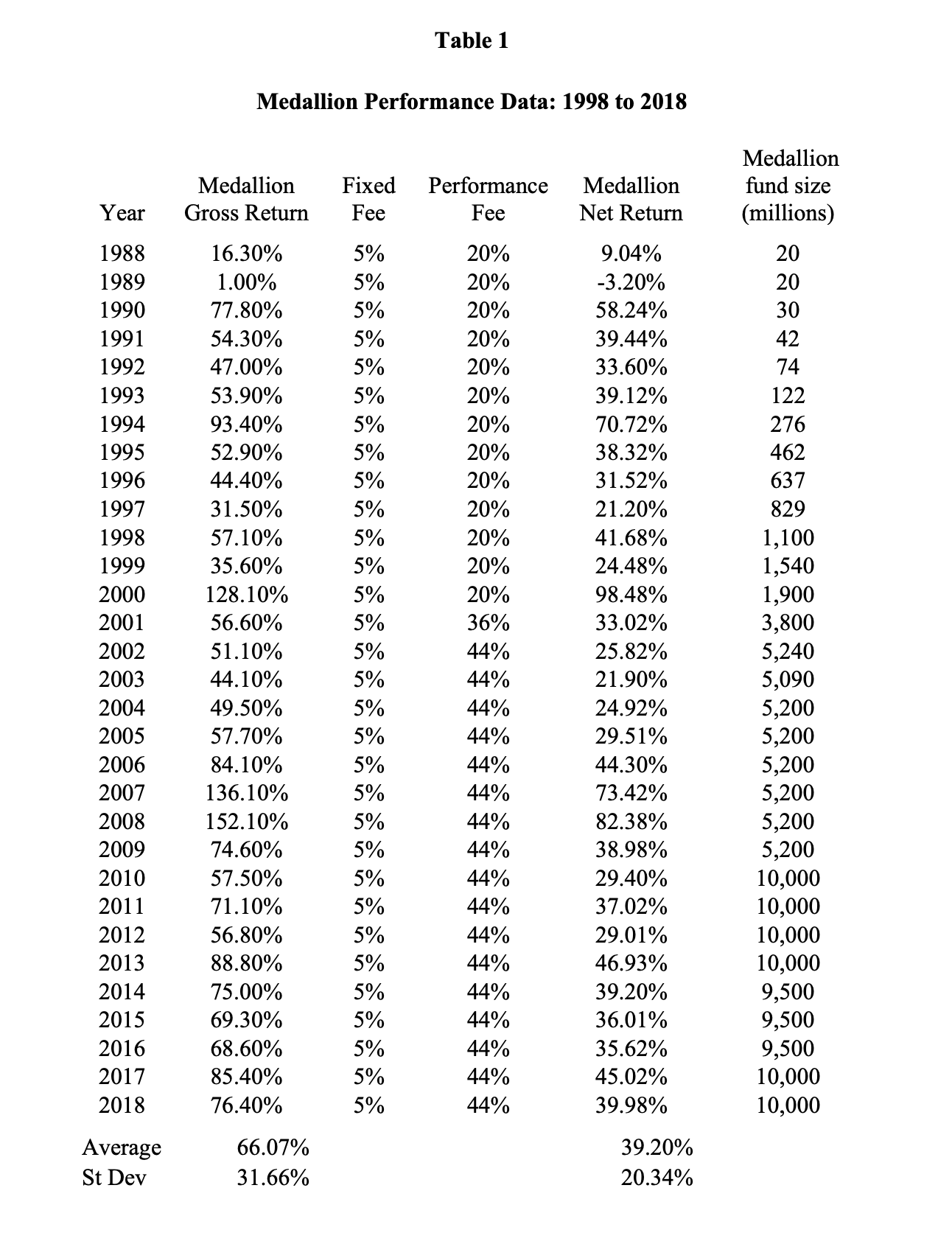

So I’ve always had an affection for such mannerisms, but intellectually I found Jim Simons interesting because I believe in human exceptionalism in the face of what might be called cosmic constraints. Oh Hayek, about your little argument on how markets incorporate all available information? That prices and crowd-sourcing are the best ways to accumulate knowledge? That led further economists to believe the market just can’t be beat, in the long run? Let me introduce you to the employees-only Medallion Fund at Jim Simons’ hedge fund, Renaissance Technologies, which has returned something like a 66% gross annual return over the last 30 years.

That shouldn’t be possible. To give some perspective, if $100 had been invested in the S&P 500 in 1988, the year I was born, it would be worth ~$2,100 now. If that same $100 had performed like the Medallion Fund did starting from that same year, it would be worth something like ~$400,000,000. Rumor had it that Jim Simons would fund economists to specifically teach the efficient market hypothesis, just to demoralize his future competitors.

Obviously, that sort of performance doesn’t mean we should throw out the efficient market hypothesis altogether. Still, Jim Simons, at least in legend, was a walking and talking contradiction to something normally considered inexorable. In this, I’m not writing about Jim Simons, the person. Talking about a life, a real life as experienced from the intrinsic perspective of a consciousness, requires dealing with how amazingly long humans actually live. Five days after Jim Simons turned seven, Hitler shot himself in the temple in his bunker. Then for Jim unfolded almost a century of experiences after that. I don’t know anything about those experiences. Was he a great father or a terrible one? Did he divorce his first wife on good terms, or was it a mess? Was he, like Warren Buffett, a connoisseur of the happy meal, or did he only drink the finest wine and eat at the most expensive restaurants? Did all his trading, all his intelligence, merely siphon away money from average Americans? I have no special insights on these questions.

I’m talking instead about what he represented culturally, at least among a certain set (he was never much for the public spotlight like some billionaires). Jim was always talked of as living proof that you could just brute-force your way through impossibilities with the right approach.

There’s actually a whole history of such things, where some armchair proof that something is impossible ends up being contradicted by actual practitioners. We humans often trap ourselves, intellectually, without much reason. Like a raccoon with its hand in a pickle jar, refusing to let go of its prize. We are comedic beings, in the end.

An example. Back when artificial neural networks came into vogue in the 80s, there was a very famous proof called the Universal Approximation Theorem. The theorem goes that for any given mathematical function, a neural network can approximate it (basically, can carry out the function). A very central result in this research was a paper in 1989 called “Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators.” What the authors showed was that a feedforward neural network with just a single hidden layer (basically input → one layer of neurons → output) could approximate any given function, and so was equivalent (in theory) to any more complicated structure, like a network with many feedforward layers, or a network with feedback (where neurons send signals back to the previous layers). The popular thinking post-proof was that there was no extra magic to be gained by playing around with exactly how the networks were organized since they would never be doing anything a single-layer neural network couldn’t. Why bother fiddling with activation functions if they’re all the same? Why bother fiddling with network architectures if they’re all the same? I’m not saying that’s right, I’m saying that’s how many thought about it.

Well, Geoffery Hinton had some other ideas about the Universal Approximation Theorem, which is why he and some graduate students showed up to one of the biggest conferences on AI in 2012 (back then, AI was still a small field) and showed massive improvement in a classic image recognition task by “just” stacking a bunch of hidden layers between input and output. Thus was born deep learning. “Deep” as in, deeper than a single-layer.

It’s not that Hinton proved the Universal Approximation Theorem wrong, exactly. It just turned out to not mean what many people assumed. The deep learning revolution was a Cambrian explosion as suddenly everyone was trying new architectures simply because they realized that such changes actually matter, leading from convolutional neural networks all the way to ChatGPT.

Such intellectual traps crop up all over human history, from Zeno’s paradox (solved by infinitesimals in calculus) to Poincaré’s three-body problem appearing problematic for physical predictions (in reality, it eventually led to a much better mathematical understanding of such systems via chaos theory) to the Michelson–Morley experiments disproving the idea of luminiferous aether (throwing much of physics into chaos and opening the door for general relativity).

In a minor cosmic irony, the research I was presenting while applying for the Simons Fellowship, the theory of causal emergence I’ve been working on for a decade, is a much lesser-known instance where everyone assumes there’s an impossible trap. Emergence, they think, cannot be reconciled with reductionism, the herald-bearer of science. In fact, there’s a famous line of reasoning called the Causal Exclusion Argument for why real emergence can’t work.

The impossibility proof for emergence goes like this: if some event occurs (like neuron A causing neuron B to fire) you can give an equivalent atomic-level description (big group of atoms we call “neuron A” causes big group of atoms we call “neuron B” to move into the microphysical state we call “firing”). If everything is accounted for in the microscale atomic-level descriptions, in that cause preceded effect, what can the macroscale (the descriptions of neurons firing) add? You can always say “magic,” but this violates the idea, one central to science, that everything is reducible to microphysics. So why not just exclude any such macroscale descriptions of the world from the causal account entirely? Such is the force of the argument that people settle on believing that everything is just void and atoms and their relations.

Except I think the macroscales of nature do add something! But rather than magic, they add something akin to error correction (a term from information theory). When a sender transmits a binary signal across a noisy wire, and the receiver gets a 0, they don’t know for sure it wasn’t supposed to be a 1. The bit might have gotten flipped. So what do you do? Well, one simple method is to send 1 a bunch of times and have the receiver average. Unless the wire is perfectly noisy (50% chance of a bit flip) then by looking at the macroscale information (the average signal received) you can tell what the sender was trying to communicate.

Similarly, at the microscale, like if a complicated state of atoms causes some other complicated state, there’s often uncertainty. Maybe it always causes it, but maybe sometimes it doesn’t, due to noise. However, up the macroscale, that uncertainty vanishes: events can reliably lead to other events. This is because macroscales can be in many different microscale configurations and still count as being the same (e.g., it doesn’t matter what exact microphysical state a neuron is in when firing, we just care that it’s firing—and the increase in reliability in the causal relationships stems from the same mathematics behind why sending 1 a bunch of times over a noisy channel works). Even though the macroscale is just a different description of the same goings on, something really does “emerge”—less errors in the causal relationships. Since philosophers usually don’t think about the math of error correction in communication channels (and the people who think about error correction usually don’t think about philosophy or causal modeling), the insight is easy to miss, and everyone instead just thinks the whole thing is impossible. But the causal exclusion argument fails, for to throw away macroscale descriptions of the world is to lose robustness in causal relationships.

Downstream effects of thinking emergence is an impossible intellectual trap include some of the more popular arguments against free will. Pick up books by Robert Sapolsky or Sam Harris to see some popularized version of the causal exclusion argument in action. What we consider impossible does, after all, matter culturally.

I’d like to think that if Jim Simons had for some reason popped his head into my presentation, he would have liked my theory for that reason. Maybe I would have gotten the three years to work on it. Or, perhaps more likely, he’d have fallen asleep. I would have appreciated it either way.

I worked at SF in an admin role a while back. Everyone liked Jim. He paid for employee vacations, spoke at employee meetings, greeted you in the elevator. You knew at some level you worked for him, not your boss. It was almost like playing. It was interesting and fun. I always described him to friends as the one good billionaire. Unfortunately new leadership seems determined to port over the worst most calcified features of the academy- like a trauma response. It's not fun anymore. It's risk management all the way down. RIP Jim.

Thank you, no stake or interest in these people or things whatsoever, but it just proves any good profile of any interesting person is itself interesting (and good for me, since I've been writing multiple entries about one such person and interview, myself).

"He too was intellectually active into his 80s, still robust, still contributing. The kind of man who didn’t treasure his body in the effete way elites do now, so afraid to smoke, so afraid to drink, so afraid of not taking the right supplements. The older class both men belonged to viewed the body as a thing to be used up, and used up well, by the end of it all."

I've been thinking about this sort of thing a lot. I'm about to turn 40, most younger people still seem to think I'm around 30. Shunryu Suzuki once said something like, "In your practice, you should consume yourself like a flame until it's all used up."

I think it's more about not becoming trapped in your (we'd say in Zen), "small-Mind," version of yourself--don't NOT take care of yourself and avoid unnecessary risks, but the idea of preserving every aspect of yourself totally deludes yourself into thinking of yourself as a separate being with no connection to the totality of a society and an ecosystem, not to mention the great numbers of people breathing in massive amounts of air pollution every day, or children in Asia and Africa scourging piles of garbage for heavy metals to sell on a daily basis. Another grotesque inequality.