Sampling the 2024 blogosphere: Part 2

The Intrinsic Perspective's summer subscriber writing extravaganza

In the spring I called for paid subscribers to send me their work to both read myself and also share links to here on TIP, along with excerpts and commentary. The results have been broken into parts. Part 2 below continues to be a safari-esque tour of the blogosphere, and as I said in Part 1:

Nowhere else can you find a collection of voices touching on such diverse topics and subjects, nowhere else is there more jungle-like pullulating (now that’s a fun word) growth.

Pullulate is still the word, and it’s worth looking through these to find new, up-and-coming, or criminally under-subscribed writers growing in the tangled banks of online blogging. This batch includes meditations on why Tokyo crows are the smartest, why beauty is just entropic fine-tuning, a confession from a boomer on why their generation let everyone else down, how the cultural revolution of the 1960s may have led to the rise of single-parenting, the grief following the death of a 7-year-old son after a car hit him, how a young blogger in college captured 1% of all internet traffic, and much more.

A few of the entries were written specifically just so they could be shared here. So please do give them at least a browse through. As before, I read and pulled excerpts for each linked piece. Initial submitted descriptions (by the authors) are in italics, whereas any thoughts / commentary I had are in regular text. Including any particular piece here is not a personal endorsement of its content, ideas, or positions.

1. “Book Review: The Two-Parent Privilege” by K. Liam Smith is a data-driven look into the rise of single parenting. Smith argues that the commonly-attributed economic causes for the rise of single-parenting do not actually line up with the phenomenon, so it must have another source.

Science is about exposing your ideas to falsification. What would falsify this argument that this was caused by economics?…If we persist at this level for a century or two it’ll look like some sudden phase transition in our culture. This is obviously extremely speculative—both the data before 1950 and after our current era—but it sure does look like we might’ve transitioned into a new social paradigm as Kearney claims… But the start of that phase transition does not line up with the 1980s.

Instead, it lines up with the end of the 1960s.

2. “Some Quick Tips on Finding Love” by Max Nussenbaum is about exactly what it sounds like.

Most people I know who are single into their thirties, my former self included, don’t end up that way because they keep getting rejected. They’re single because they struggle to meet anyone they really like. That situation is dangerous, because it can lead you to think that your problem is all these other people. I’ll concede that it’s possible to go on ten, twenty, or even thirty dates with people you don’t like just because you got a string of bum luck. But if such a pattern continues for long enough, eventually you have to acknowledge that there’s one consistent factor in all these bad dates: your presence.

3. "On Jargon" by Tim Dingman is about how and why elites poison everyday discourse with technical terminology, and what to do about it.

Elites have the desire and ability to spend time on topics that can use specialized knowledge. Since their peer group is other elites, they have ample opportunity to display and be rewarded for their jargon.

As a result, elites are far more likely to use jargon, in all settings.

For the same reasons, elites are likely to view general topics through a specialized lens. The most common use of an inappropriately specialized lens is in politics. Elites believe social problems are legible to, and solvable by, those with the right knowledge: elites.

As Tim lists a number of reasons for why people do end up using jargon (most of them he judges bad) this got me thinking: I’ll add that jargon is also used to make ideas seem more original. If you can give a name to something it makes it seem more irreducible than if you just defined it using its components, which themselves then seem the important irreducible atomic bits. By uniquely naming things, you make it seem like you, and you alone, invented them. I therefore dub this motive for jargon “anxiety-of-influence-jargon” and encourage everyone to use that term to describe the phenomenon, since clearly new jargon is needed to discuss the ever-growing piles of jargon around us.

4. “Beauty as entropic fine-tuning” by Åsmund Folkestad is about why beauty should be measured in bits, why conscious AI would experience beauty, and the evolutionary function of the aesthetic experience.

Over several years now, a single question has refused to leave me: what is beauty? Triggering it was a series of aesthetic experiences so intense that I count them among the most significant moments of my life… I'm a theoretical physicist thinking about black holes for a living…

The view of beauty advocated here meshes well with a theory of brain function known as predictive processing. According to the theory of predictive processing, the brain constantly tries to predict what its sensory input will be in the near future, compares the resulting input with its prediction, and then updates its internal world-model in order to improve its future predictions. Thus, according to this theory, the accurate prediction of future sensory signals, i.e. surprise-minimization(=entropy-minimization), is a fundamental task of the brain. It would thus be wholly unsurprising that a sense of pleasure is dispensed when we successfully improve in surprise-minimization.

5. “Nothing Matters, So Be Kind” by Andrei Atanasov is about how the movie Everything Everywhere All At Once taught him perspective. This made me really want to see Everything Everywhere All At Once, which I shamefully have not.

To my understanding, the bagel and the googly eye represent two sides of the same coin. They’re two opposing perspectives, stemming from the same basic idea. The bagel is the yin—the dark, nihilistic, pessimistic view of the world, while the googly eye is the yang—its lighter, kinder sibling.

They both begin from the premise that life has no inherent purpose.

What the nihilist fails (or refuses) to grasp is that, even though there’s no objective meaning to anything, that doesn’t stop us from creating our own subjective meanings. It doesn’t stop us from deciding what’s important to us.

6. “How the iPhone stole our free time” by Michael Gentle, shows how the internet and mobile technology gradually eliminated the notion of free time and being unreachable. Continuing on the theme, this again starts with a movie I should probably see at this point.

Everything Everywhere All at Once might make for a catchy movie title, but it’s no way to run our lives… Even during the early years of the internet, there was no attention economy as we know it today. Nobody was vying for your attention or your money online. The internet was just a tool you used for a specific task, like online searching or email. You found a computer (at home, in a library or in an internet café) and logged on via a modem. And when you were done, you left and got on with your life.

7. “Connection” by Drew Murdock looks at Taylor Swift and what makes her relationship with her fans so unique.

Her performance amazed me that night. My expectations were high, and she didn’t come close to disappointing. Taylor occupies a unique category of performer; she is not just a singer, but a true entertainer. She tells us stories and hints at what song is coming up next. She travels around the stadium to allow everyone a close look at the most famous woman in the world. She plays songs for her newest fans while also showing signs of respect to her oldest and most loyal. Of course, she sings and dances, but I think the most unique part of her performance is the purpose. I don’t think many of her fans go to hear her sing or watch her dance, I know I don’t. They go to show their appreciation. They go to show how impactful her words have been. They go to be a part of something bigger. A Taylor Swift concert is less about the musical performance and more about celebrating the art she’s created for the masses. It’s so distinct.

I think this provides a good explanation for Swift’s popularity, which some people seem to find so mysterious—she is very involved in her community and caters to them in ways that other stars don’t.

8. "Against Julian Jaynes' Reading of the Iliad" by Scott Thomson contends that Jaynes' Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind blatantly and probably deliberately misreads the poem, and thus fails to do justice to the inner lives of Homer's fully conscious characters. This is a subject close to my own heart, as I address it in my book The World Behind the World (which Scott references). Scott takes an even stronger stance than I: that Jaynes is willfully misreading the evidence for “modern minds” in Homer.

When I see things like “[the Iliad] really is about Achilles’ acts and their consequences, not about his mind” I want to throw his book across the room (however, because it’s on my phone, I don’t).

Rather than as commandments from some split consciousness, Scott thinks that:

In short, Homer uses his characters’ encounters with divine voices the same way modern writers use the devices available to them: to establish character and to advance the plot.

I’m sympathetic to this. I think the only defense that Jaynes himself might offer is that he basically thinks translators insert modern minds into their translations to make them more, well, modern. The issue with this retort is that it makes Jaynes’ ideas extremely hard to falsify, since he can always just say “Oh, but they put that in during the translation.”

9. "How I almost slept on the street in Mexico" by Warrior Heart is about the grace of a stranger saving him from sleeping outside the first night of his vacation in Mexico.

I knew the first place I would go after dropping my bags at the Airbnb was the ocean. As I was traveling alone, I felt uncomfortable bringing my phone, wallet or house keys to the beach. There was a little four digit lockbox to store the keys next to the door to the house. As the code was only four numbers, I figured it would be easy to memorize. So when I went to the beach I left my phone, wallet and house keys behind. Water, a bag of granola and the clothes on my body were all I brought to the beach. After a lovely swim, I went back to the house. I popped open the lockbox and spun the dial to the code. The lock box did not open. A second try. This time a slightly different number. Still no luck. The code was gone from my mind.

10. “The Art of Training Young People” by Benjamin Parry argues for apprenticeship as a forgotten source of creative capacity, economic prosperity, and social liberation. This has a bunch of interesting notes on the history of apprenticeship. I personally couldn’t help but notice that the timespan of apprenticeships of old is pretty close to the time a graduate student spends training at their own craft.

The period of apprenticeship began young, usually around the age of 13, so the contracts were often brokered by the apprentice’s parent or guardian… Commonly the tenure for the apprenticeship was in the range of 7 years. During this time the apprentice lived with the master, receiving free room and board as well as some very modest form of compensation. In the final years the apprentice would 'graduate' to become a journeyman or a freeman - a recognised skilled craftsman in their own right - and receive the wages appropriate to that role while still in the master’s shop.

11. "Microbial Time" by Siv Watkins is an exploration of the perception of time, from human and microbial perspectives.

Clock proteins, in organisms with life spans longer than a day, are made and broken down in 24 hour iterations. Plants seem to exist much more slowly than we do, but to them, an hour is still an hour, a second is still a second: there is temporal succession.

Within the microbial universe, these ideas are nuanced. In many cases the ability to track biological time imparts evolutionary fitness, but in others — why follow a 24 hour clock if you don’t even live that long?

12. “On the random origin of Merit” by Ax Ganto is about how the notion of Merit is essential to the development of societies in part because it contains a random, unfair element as critics point out.

The meritocracy debate is one of those issues. You know, the ones that never end, that seem like they can’t be resolved, ever. Euthanasia, gun control, Israel-Palestine and the like. The issues that seem like we need them to exist more than they need us to solve them.

Ganto’s argument is essentially a counterargument to what is usually the first go-to, and primary, critique of meritocracy: that it is actually unfair. Unfair because you don’t get to choose your genes, your family, your initial station in life, all the little steps that go into success. Ganto argues a sort of reductio of this, imagining that everything is fair and therefore controlled for, and how uninteresting that would make, say, sports competitions (and life in general).

What I am suggesting is that the concept of “fair competition” is meaningless. Someone always comes out on top. This criticism (unfairness) makes a fundamental mistake in thinking that there could be a fair competition on equal footing. But that is non-sensical because if they were really, truly on equal footing, the outcomes would always be a draw - by definition… The goal of competition (in sports, education, or society at large) is not and never was to have everyone be as skilled as everyone else. It’s to find out what makes someone better…. A person deserves his achievements if the reasons for his success are not clearly identified and if there is no way to control them.

13. “How my generation let down our students” by John Keith Hart is a confession.

There is no reason why students seeking higher education in this century should look to these universities; it was us, the lucky beneficiaries of our parents' war, who threw it all away…

John goes on to point out that when he first applied for university positions after his PhD, there were 23 available to him. One, apparently, had no applicants at all!

Soon after I first posted this essay in a blog some 15 years ago, a young man approached me to ask if I minded him reposting it. I asked him where that would be. He and some others had launched a site called ‘Generation’. Its aim was to prepare for the coming war between the generations by assembling useful documents and providing a forum for discussion. He told me that my essay was a rare example where a boomer academic had owned up to our crimes against them. I felt compelled to tell him that, in any war between his generation and mine, their side would lose. We not only have most of the money and power, but my generation would never have asked for permission.

14. “I wrote about resilience before my son died. Here’s what I got wrong” by Ben Baran is about how a personal tragedy expanded and deepened his perspective on psychological resilience far beyond that which he had studied for more than a decade before as a social scientist. This was a very difficult read for me, for obvious reasons (I can’t really consume films or books or stories where children die anymore), but it was illuminating about the difference between academic knowledge and personal experience.

On Nov. 7, 2020, a driver exited a parking lot without looking, and while crossing the sidewalk, hit my 7-year-old son, Vincent. He was riding his bicycle with his three siblings and my wife; they were on their way to their favorite ice cream shop after playing at a local park. Vincent died within minutes….

In retrospect and through the lens of the crucible of Vincent’s death, reading what I wrote about psychological resilience has a surreal aura. I missed a few key points about the topic, as I’ve outlined here, but that’s not all I think about when reading those rather naïve words. I also consider who I was then juxtaposed with who I am now, with the younger version of myself seeming like one who was describing air travel based upon reports of other travelers, or picturing a foreign city based solely upon a postcard. Much like words fail to describe the complexities of life, love, and death; mechanical scientific reviews can only do so much in providing an understanding of human existence.

15. “Poignant Assholes” by Michelle Syba is a list of Canadian literary fiction that captures the consciousnesses of difficult people and that inspired her story collection, End Times (Freehand Books, 2023).

Why was I drawn to these people in my writing? Was I a misanthrope malgré moi? Part of the reason is that I’m curious about people I don’t readily like. But just as importantly, maybe more importantly, my characters refract the influences of stories that I have read and loved.

It’s a good phrase, “poignant assholes,” because that’s indeed what’s attractive about so much fiction. Although, perhaps it is not so much that assholes are especially interesting as the opposite, in that niceness and boringness are so closely tied that they are often indistinguishable, and so they make bad qualities for protagonists.

16. "My Year of De-Googling" chronicles Joshua Skaggs's ill-advised efforts to rid his life of all Google apps.

Trying Google alternatives is like swapping your steering wheel for a squishy joystick because it’s more “ergonomically correct,” which is fine until someone wants to borrow your car. You never realized how easy it was to rattle off your email address and close with “@gmail.com” until you have to spell out “P-R-O-T-O-N-mail” twice a week. You start to suspect that maybe you’re the idiot here.

My sympathies on this one: I once wanted to migrate away from Apple products and basically realized at some point it was simply too complicated and I was stuck in the ecosystem until the day I die.

17. "Crow Moon 2024" is about the genius crows of Tokyo and what they have to teach us about life.

… the most brilliant crows—the true geniuses of the Corvid family—are the jungle crows of Tokyo, Japan. They use crosswalks. They operate water fountains, turning the handles slightly when they want a drink and cranking them all the way when they want a bath. They’ve even been known to place walnuts under the tires of cars idling at red lights, knowing that the otherwise unbreakable shells will soon be cracked open. … Worst of all, they use stolen clothes hangers made out of wire to build their nests in power lines, a practice that has caused widespread blackouts and brought high-speed bullet trains to a screeching halt.

But I’ll note, this essay is secretly about much more than just crows—it is about why to write haikus in the face of the death.

18. "How to Fight for Justice Over a Dinner Check” by author and screenwriter Geoff Rodkey, seeks to answer the question of how to maintain financial parity when eating out with friends who drink more than you do, and is one of several installments of Bad Advice, a column offering thoughtful, empathetic, totally misguided solutions to a variety of modern problems. Geoff’s solution is very much an eye-for-an-eye biblical one. When being outspent at the dinner table with no expectation of renumeration, simply:

Keep score. Ruthlessly. Maintain a running tally of everybody’s tab—write it on the tablecloth if you have to—and don’t let a single goddam person at that table outspend you. You’re going to be way behind on the drinks, so you’ll need to make up the difference in food. For every drink somebody else orders, pile on an appetizer.

Did the college friend sitting across from you ask for an Aperol spritz? Get yourself some jalapeño poppers. If the poppers cost less than the spritz, throw in some cheese fries. At no point should you offer to share your appetizers. That would defeat the whole purpose. This is your food. Not theirs.

19. “The Lifecycle of a Dream” by Mark Koslow is about letting go of his dream to become a tech entrepreneur.

If I'm honest with myself, I may just not be well-suited for trying to found the next unicorn. My genuine interests are academic: I enjoy things like reading, teaching, talking, and writing. I take my time with things – friends joke that I put the "slow" in Koslow. I consider things to a fault – you may have noticed – and second-guess myself often. These would all be liabilities in a founder. I also don’t have that special breed of relentless, starving ambition anymore. What once felt like a rolling boil now feels like a consistent simmer. That is to say, I feel more Fundamentally Okay now. I think meditation medicated me. Or maybe it was just getting a bit older. Probably both.

I wonder if this dream was ever genuine. Or if it was just a shiny thing I picked up in college, admired, and adopted as my own. I think it had little to do with the actual day-to-day work of being a founder, and everything to do with the identity of being a founder, and the benefits of that identity, like respect, status, purpose – the usual suspects. I didn’t realize then, but I see now, that my dreams should be downstream of what I want to do in the world, not borrowed ideas of who I want to become.

20. "The First Online Writer" by Michael Dean casts back to 1994 to profile Justin Hall, the first Internet-native celebrity, who spilled his consciousness into a hypertext maze before the era of search engines and social media. This is such an interesting historical note, one I had no idea of: in the initial days of the internet, Justin Hall, just in college, was a blogger capturing 1% of all internet traffic.

No one’s seen anything like it, and so naturally your homepage becomes the portal to the early Internet. You have so much traffic you crash the servers at your college. By 1995, your website hits 27,000 daily views, 4x the traffic of Yahoo!,1 and 1% of all Internet traffic (for context, that’s the same relative size of Mr. Beast, who now gets 360 million views a day)….

The breaking point came when his own audience began dissecting, analyzing, and rooting against his relationships. Justin was falling in love, but his readers started citing episodes from past failed relationships in his comments. They formed theories around Justin’s personality; they weren’t wrong. His new girlfriend was freaked out, and he had to decide between his website and a real person.

At this point, self-publishing wasn’t serving him anymore; it pissed off his friends and family, it lost him jobs, and it threatened his future. He got hit with the dark consequences of oversharing, and decided to sign off in 2005.

21. “Notes from what I guess counts as the bleeding edge of artistic possibility these days” by William Collen is about how the output of the AI image generators is becoming progressively more predictable, boring, and stylistically tame as time goes on.

DALLE3 can produce images of astoundingly diverse styles and kinds. At first this might seem like a good thing; isn’t it good that we are able to produce so many different kinds of illustrations? Certainly in a human artist, the ability to be versatile would be an asset. But the best artists seem to be the ones who get fixated on a small handful of very specific artistic problems and attend to them with meticulous focus, thereby producing an easily recognized, signature style. Even in the field of commercial illustration the best practitioners commonly cultivate a personal style. Consider Roz Chast; she has been cranking out cartoons for The New Yorker in exactly the same style for more than forty years. The history of commercial illustration stretches all the way back from Mary Engelbreit to Norman Rockwell to Charles Dana Gibson to Albrecht Dürer—and all of these people, and many more besides, are known as much for their signature style as for their typical subject matter. Despite not being part of the high tradition of art, illustrators are able to express their unique outlook on life through how they style their work. Why, then, would we want something that can merely ape the already established stylistic conventions? Don’t we want something that can be original?

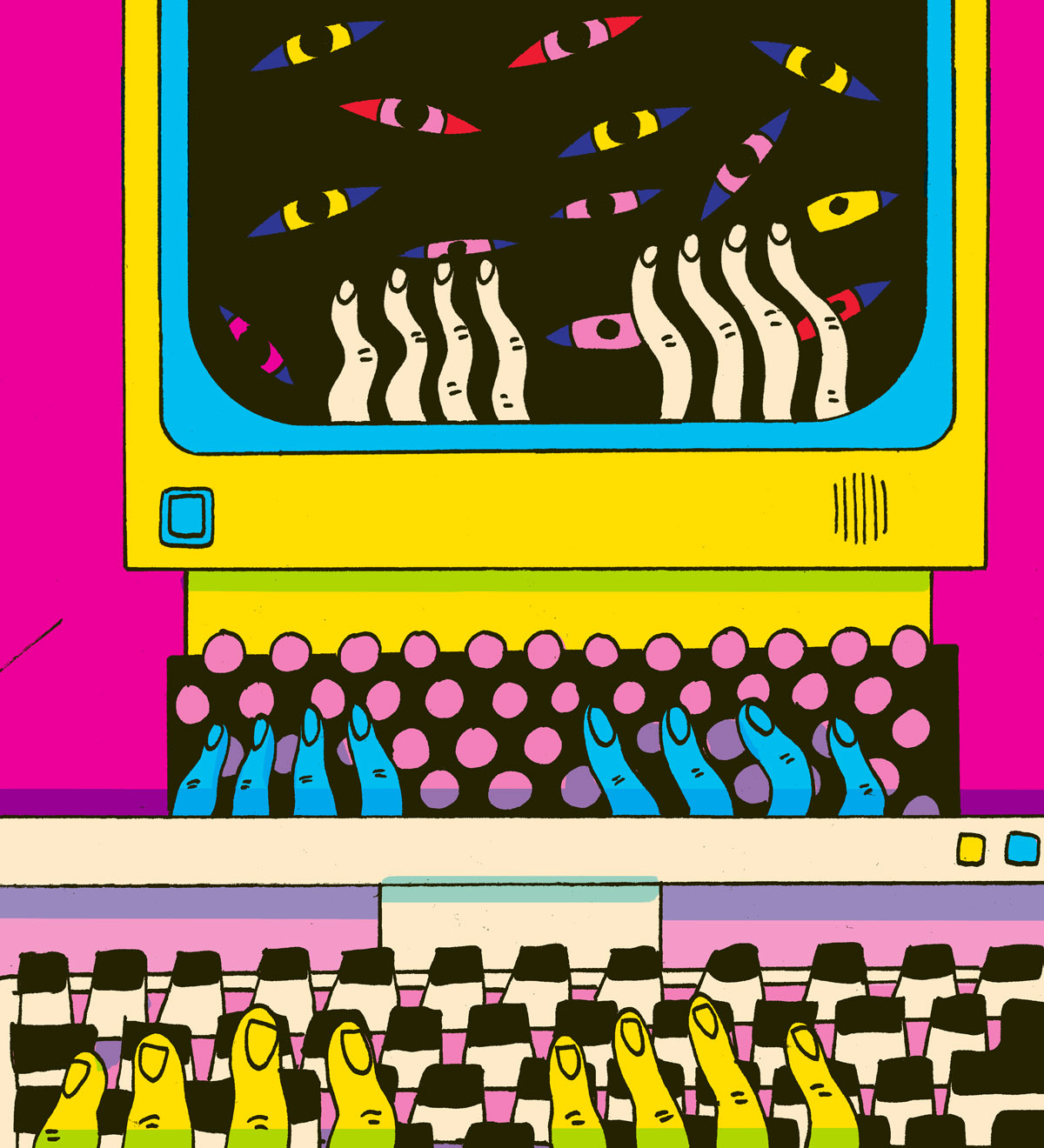

Also, great to see mentioned Alexander Naughton, the resident illustrator of TIP. For Alex does, as William points out, essentially respond to an art “prompt” in the form of my draft of an essay, which Alex receives ahead of time and does art for with, well, I’d say “inhuman” quickness but there’s nothing inhuman about it.

In a fascinating discussion of his own creative process, Alexander Naughton reveals the way he responds to what amounts to a very, very long text prompt—the text of an essay for which he has been commissioned to provide the hero image… By creating a piece of art, Naughton—and every other human artist—opens himself up to failure.

22. “We Have Made Science!” by Sebastian Ruf is a scientific paper parody poking fun at all the worst parts of scientific publishing.

Abstract

Science is very important. It has been studied for many years, yet no one has studied this science. It is the most beautiful science, it is our child. In this paper, we prove that we have made science. It is the best science that there ever was, also there are many, many caveats.

As a peer-reviewer, I can say this was more science than I ever thought possible, an amount of science so dense one might say it is a black hole of science—never has anyone scienced harder than this.

23. “AI Is Both” by Malcolm Murray is about the need to bridge the chasm between different camps in order for society to manage the risks from advanced AI.

Those working on AI discrimination use different tools and different techniques than those working on AI misuse risks. They tend to talk past one another or distrust others’ methods…

Malcolm gives a description of what I think is the easiest-to-understand argument for AI risk, as well as the least assailable (due to its broad nature).

Introducing new forms of intelligence that will have goals and ways to achieve them that are completely alien to humans can therefore be seen as bringing about a whole new life form. Seeing AI from this view brings in a completely new set of base rates. The last time a new intelligent species was introduced in the world, in the form of Homo Sapiens, it seemed to have non-negligent negative impact on existing species, to say the least.

24. “A Day in Berkeley” by David Gasca is about the lessons learned from a full day of walking in Berkeley, California.

One of my role models is a man named Craig Mod that lives in Japan and routinely goes on long walks… Many of his walks are quasi-monastic in nature: he walks alone with his camera, dictating notes and thoughts into his phone, and then writes newsletter about his experiences at the end of each day. He routinely compiles his work into broader books that he sells online. Craig is an artist, writer, walker and philosopher. A foot-powered thinker for our modern times. Since I have come into more free time recently, I decided to take Craig’s rules for walking and turn them into reality… My first foray: Berkeley.

25. “Energizing Below Our Maximum: Efficiency as Performance Enhancement” by Kameron Sanzo, unpacks the athletic language of productivity culture and argues that, when we use athletic and energy language to discuss our work's efficiency, we are drawing upon a specific and exploitative lineage in the history of energy physics and its impact on the western cultural imagination.

What if I claimed I could teach you how to minimize (or eliminate!) fatigue during your work day without recourse to wasting all that time on sleep? Or, what if I claimed I could guarantee your career success by sharing tips and tricks to maximize your work output? Would you buy my book?

I have been fascinated and repulsed by the self-help genre for literally half of my life. When I was a teenager, I dreamed of publishing a satire of your typical best-selling self-help text.

I'm always impressed by your generosity when you do these, and the variety of responses you get is a real testament to the broadness of your mind.

I will share here my response to Tim Dingman's post "On Jargon:"

Fantastic read. Somewhat related, somewhat tangential, one of my posts will be about (with imprecise measures of tongue and cheek) "the etymological fossil record" of "Classification warfare." Most words that now have reductive implications originally had the inverse sentiment or context in its etymology. Words like quaint, trite, contrived, trivial, arbitrary, mere and mundane all had positive implications or neutral-to-positive use cases.

For example, "trivial" comes from Trivium which is literally a common meeting place or common ground (where roads intersect). However, if you trivialize the common people as "commoners," the implication is clearly bad. Ironically, common ground is now valuable because of its... uh... rarity.

Similarly, "arbitrary" came from arbiters arbitrating, a use case which still survives. An arbiter has a specialized role as an umpire or mediator and therefore relies on trust in their professional opinion. But something that is arbitrary is "contrived as if by mere opinion," and may be no better than any other random opinion. Such a link might seem a stretch, but just look at what is happening to the words "elite" and "privilege" as is implied by your own use.

There's a way in which the rhetorical use of jargonificationalism manages to draw the exact attention you hope to evade, and your words will resurrect to pataphysique your obdurance.

The etymologies were sourced from etymonline