Secrets of the publishing industry

How to publish your book and get it attention, an anti-lesson

At the age of 24, and worried about being driven out of graduate school due to a contentious relationship with my PhD advisor over our research, I did what any sensible young neuroscientist would do: I started writing a novel. My ambition was to popularize the ongoing search for a theory of consciousness—for that is where science is at its most literary, where it confronts, as every fiction author must, the inner workings of the human mind. Their duel with subjectivity highlights the subjectivity of scientists themselves, and I wanted to present them as people, not eggheads, who sometimes smoke cigarettes and make mistakes and develop factious relationships and have sex and aren’t just bland-faced Jeopardy contestants without drives or human interests. The draft was mostly finished by the time I was 27, although it would go through rounds of editing later on, and The Revelations was finally published last Spring.

The publishing industry is strange, and full of obtuse complexities that can lead to tragedy (I’ve previously written about a little-known blogger I followed whose search for a book deal led to him being killed in 2016). It’s an industry with a relativistic quality. Time distends or speeds up, never to your advantage. Interminably waiting for publication takes years, and then, once it happens, it passes all too quickly.

So quickly that this month Abrams Books shipped me some advanced copies of the paperback version of The Revelations:

So on this, the day after its official paperback release, I’d like to share an “insider’s perspective” on the publishing industry, including little-known secrets about how to publish a book—as well as pinpoint the exact moment where I failed. For, even if you follow the The Intrinsic Perspective, you probably haven’t read The Revelations, nor perhaps even heard of it, and I’m going to tell you why.

Alternatively, if you want the inside scoop you could bid $200 (N.b., proceeds went to charity) for a 30-minute meeting with David Varno, the Fiction Reviews editor for Publishers Weekly, which might be especially attractive since:

In addition to receiving this Zoom consultation with David, Walsh Whiskey will also ship you a bottle of Writer's Tears. . .

The reason you might want the Writer’s Tears is that getting published is, no lie, incredibly difficult. Think of it like a chain of successive events, a chain that goes manuscript → pitch → getting an agent → getting a publisher → getting good reviews → getting sales. A successful book is so rare precisely because it needs to pass through a sequence of these “Hard Steps” wherein each conditional step has a low probability. And chains of low probabilities lead to vanishing infinitesimals, e.g., even if the conditional probabilities between steps were all the fair coin flip of a 50% chance, then P(manuscript|pitch) * P(agent|pitch) * P(publisher|agent) * P(reviews|publisher) * P(sales|reviews) would equal only a 3% chance! And in reality 50% is far too high. Interestingly, this sort of Hard Step model also explains why life in the galaxy is rare—so many things need to go right in succession that, once you chain it all together, it’s almost impossible. Just as how planets with life must be vanishingly rare, most written manuscripts fail to get published, let alone accrue readers.

Yet these industry Hard Steps can, in certain ways, be gamed. Starting with

creating a publishable manuscript.

The most common mistake in publishing, one perhaps almost universal, is to think that what matters is the potential of a manuscript. Surely the genius of the project will glint through! But what actually matters is whether, at any point in the long chain of the Hard Steps, anyone has a single reason to put the manuscript down. This is especially relevant for the first one hundred pages, or roughly the first three chapters. Almost nothing else will matter—most agents or editors or reviewers will have come close to their final decisions by then. So for the beginning, polish, polish, polish, as if the rest of the book doesn’t even matter. For it’s only a slight exaggeration to say a manuscript could make it through the Hard Steps with a perfect hundred first pages but with the remainder as jabberwocky.

Of course, once past the “good enough” level, writing is unavoidably subjective. How “good” a manuscript is can shift depending on the perceptions the reader has going in, which is why you need

blurbs.

Wait, blurbs? But Erik, I don’t even have a literary agent yet. Shouldn’t my book be published, or at least in the pipeline, and then I am blurbed?

Almost everything in the process is going to seem unfair like this. Causality is reversed—publication is often reserved for those who already have good blurbs from famous writers (both fiction and nonfiction).

But how is that even possible? Normally, it wouldn’t be. But a lot of writers come out of MFA programs now, and most professional writers earn their living as professors, who will then provide blurbs for their students’ manuscripts (just like letters of recommendation). If you’re not coming out of an MFA program (I did not) then you’re in for a rough time, because you’ll have to beg famous strangers to read your manuscript and offer an advanced blurb—equivalent to saying “Hey, can I take 20 hours of your time?”

Luckily, people are fundamentally good, and you only need one or two to get started. E.g., I had previously corresponded with Peter Watts, Hugo-award winner and author of some of my favorite sci-fi novels like Blindsight and Starfish. My manuscript wasn’t sci-fi, but it was about consciousness and the practice of science itself, which are themes he’s concerned with. Peter gave me this incredibly punchy blurb:

Sex. Death. Rioting in the streets and aggressive self-lobotomy; brains in vats and the nature of consciousness itself. Dense, literary, and hallucinogenic, The Revelations is an impassioned argument over beers and amphetamines. It will be stuck in my brain for some time to come.

which ended up on the back cover of the actual hardcover book when it finally came out. I cannot stress how kind it was for Peter Watts to read the manuscript (very much a rough draft at the time). Another instrumental writer was Andre Dubus III, author of beautiful psychological portraits like the Oprah's Book Club selection House of Sand and Fog and his memoir Townie. With Andre I was simply lucky—the independent bookstore my mother owns is one he frequents and has done events at. Andre, however, went above and beyond, not only giving me a blurb but talking up my book everywhere and also hosting my digital book launch party (my physical launch party was at the store itself).

While you don’t technically need blurbs when pitching agents, literary agents get roughly 25-100 new manuscript pitches per day. So of course they have to use things like MFA program prestige, previous publications, and, especially, blurbs from other authors, to filter their email down. Which brings us to

submitting to agents.

Literary agents are an exhaustible and finite resource—you can only submit to agents once. Every time they say no (and most will), that’s one more you don’t get to query again. There are probably only a couple hundred really good literary agents (the industry is mostly limited to NYC) and this supply goes fast (I recommend this list of agents over at The Novelleist).

Therefore, you must personalize every email to an agent, which is worth it because in the Hard Step model of publishing the most important stages are the first steps. E.g., my fiction agent Adam Schear was an incredible agent—he not only fought tooth and nail for the book, he also legitimately improved it. But he himself is not super-famous (though he should be), so selling the book required a lot of legwork by him. The second book I sold was nonfiction, which is generally easier than fiction. But I also had Susan Golomb selling it, and she’s a very famous agent (she’s Jonathan Franzen’s agent, along with a host of other talented writers). Such things help inordinately when

your agent submits to publishers.

And gets rejections. Well, at least some, as your agent wines and dines editors (or you know, emails them). Sometimes the rejections are frustratingly close. Here are some rejections I received back in 2019 from big publishers (kept anonymous). They were things like:

I was really impressed by the book, which is clearly deeply researched and shows real erudition. I found the Crick fellows charming and believable, and I was fascinated by the novel and challenging insights into neuroscience and consciousness. The book conveys a real passion for these topics, and for NYC, which is wonderfully brought to life. But that said, I’m afraid I won’t be coming through with an offer toward publication. This wasn’t an easy call, as I admire so many elements of the novel. But ultimately I found it slightly too discursive for my taste, and I didn’t find myself pulled in by the narrative momentum as much as I hoped.

whereas others rejected based on perceived market fit:

Erik’s capacious intellect is really nothing short of stunning, and it’s amazing how wide reaching his intellectual pursuits go in this book. I love the tight cast of characters he’s put into this pressure cooker environment, and some of his prose is really breathtaking, especially his descriptions of NYC. My principal worry is that this kind of serious (dare I even say Franzen-esque novel) about a tortured male genius is a tough sell in this moment, and so I feel like I’d have to be so confident it could surpass those challenges.

and

I really enjoyed diving into this and found the writing electrifying and deeply insightful at times. The main issue for me right now is Kierk. He isn’t necessarily unlikeable (and besides, unlikeable characters are often the most fun to read) but I do worry that a perspective like his—very male, very intellectual, and usually the smartest in the room—would be tough to position to our audiences without there being a lighter, more overtly speculative angle to the story soften it. I was personally intrigued by his story and the questions of consciousness that plague him—the author’s expertise seems to be drawn on often, and usefully, throughout—but I still worry we’d have trouble breaking this out to a wider audience, despite the author’s credentials and the clear strength of the writing.

(By the way, I didn’t find these rejections unfair—they are simply saying, either (a) we think the book itself has a minor flaw and that’s enough to reject, or (b) we don’t think there’s an easy market for it.)

If a big publisher comes in with an offer, the amount of money will likely between $10,000 and $100,000. That may seem like a lot, but given the hours spent writing and working it through the publication process the real numbers are minimum wage, at best. Your agent takes 15% (they deserve it). Most of the serious money is made on re-sales of the rights, once there’s some buzz. A popular book might get “only” a $100,000 advance for US rights, but then another $30,000 for UK rights, another $30,000 for German rights, etc. In my case, Abrams Books, one of the big publishers, came in with a $20,000 offer. While it was for the lower end of the range in terms of price, they offered a generous total print run for a first-time author, which implied good distribution, and Abrams did a really great job on editing and design.

After working with your editor to sharpen the manuscript, it’s time for

blurbs (again).

That’s right. But it’s slightly easier now, as the assurance of future publication precludes you handing blurbers a steaming mess. In total I hustled my way to a dozen blurbs from kind and amazing fellow writers—my publisher got only one blurb for the book (getting blurbs is tough!). Another place where you can put your thumb on the scale is on

cover design.

Well, honestly, you mostly get no say for the big design decisions. But you can burn social capital with your publisher to veto the absolute worst designs, as well as to make small improvements to what they do give you. Natasha Joukovsky over at Quite Useless spotted a spelling error on her book cover (actually, her mom spotted it) and got the publisher to reprint it, but not before half the initial print run had been sold. Let’s move on to

early ratings online.

Whether a book succeeds in terms of sales is extremely dependent on whether it keeps selling long enough to penetrate its target demographics. Take The Revelations—its target audience is people who love hyper-intellectual books like The Name of the Rose or House of Leaves or, if nonfiction, Gödel, Escher, Bach, or, (if using TV shows as a comparison title, as is sometimes done), those who enjoyed Alex Garland’s Devs. Publishers are generally averse to books with target demographics like this. Perhaps because they realize what the real difficulty of publishing is that any new book from an unknown author must first do well within the demographic of people who read mostly new books by unknown authors.

I.e., most readers (including often myself) are bottom-feeders, happy to let the good stuff filter down to them and ignore the noise. Meaning they spend most of their time with books more than ten years old; only a slim minority of readers spend an inordinate amount of time on books less than one year old. But that’s the very demographic that determines if a book is successful, since they are statistically over-represented there! E.g., your book starts out being reviewed on Goodreads before it’s even published via a program wherein people sign up to receive free new ebooks in exchange for a promise to write a review—but again, the type of person who would sign up for such a free ebook service is an incredibly specific demographic, so you first have to penetrate that demographic, score well with them, and only then move on to yours. This can be nearly impossible, although there are shortcuts between demographics in the form of

professional reviewers: the final boss (and where I failed).

I didn’t fail by getting bad reviews. I failed by getting no reviews. I foolishly assumed that, unlike literally every other step in this process, reviews were something that happened naturally. They would just spring out of the ground like mushrooms. Sure, perhaps not at The New York Times or Entertainment Weekly, but there are hundreds of outlets with book editors (including most online magazines); certainly I was expecting reviews in the places geared around book reviews: Bookforum, Book Riot, Book Page, City Book Review, Electric Literature, Lit Hub, The Millions, or the many other dedicated institutions like New York Review of Books, London Review of Books, Chicago Review of Books, LA Review of Books, etc. Keep in mind—due to the generous initial print run and good within-industry marketing Barnes & Noble bought, in advance, three copies for every store in America.

Somebody had to cover it, right?

Nope. Oh, there was a smattering of mentions online around publication (like a glowing review in Berfois magazine, and a mention at Crimereads), but no reviews in the standard review outlets, nor in any big outlets at all. It was as if it had never been published.

Although there was one traditional outlet which did actually review it. None other than the fiction section of Publisher’s Weekly. But they got plot wrong. The (unintentionally hilarious) positive but short review claimed, among other things, that the central plot was that the main character had been “tapped by the Department of Defense to help with a mind control program.” Except this isn’t what happens in the book—there is a New York University fellowship that brings together researchers searching for a scientific theory of consciousness (one of whom gets murdered). But there’s no government mind control program.

I’m harping on this for a reason, which is to express what no one else will tell you: the likelihood that you get reviews just for publishing a book is extremely low. My total rube-like lack of knowledge about this is why hardcover copies of The Revelations are currently on sale for $3 on Amazon—Amazon bought a bunch in anticipation for sales, probably just based on the print run and marketing materials and, without any corresponding reviews, sales (relative the print run, it’s not like no one read it) were not what they calculated. All to say, if you plotted 2021 book releases with “distribution” on the x-axis and “# of reviews” on the y-axis, The Revelations would almost assuredly be one of the lowest dots in the bottom right quadrant.

I’ll take some of that Writer’s Tears now, thank you.

And let me present the other side as well: sometimes reviews don’t seem to drive sales at all, even really good reviews in prestigious outlets. For instance, another author who was also in my cohort as a NYC emerging writers fellow (a prestigious fellowship, often a pipeline to future publication) got a bunch of reviews, including a dazzling one in the New York Times. But the sales for her just didn’t materialize.

Which brings me to

publicists.

When a book comes out and suddenly the author is everywhere, on every podcast—do you think they arranged all that themselves? No, they either have a good in-house publicist or they hired a private one. The advertising of books is like the advertising of anything else: money in, money out. And this is one of the greatest illusions of the industry: there is no frictionless free market for books. If you think about it, how could there be, given the subjectivity of books plus the time-commitments to reading them? It’s a recipe for a steep playing field. Book sales are instead mostly driven by advertising via the in-house connections of the publishing companies themselves.

But I don’t have a publicist! You might be thinking to yourself. Well, then you have a problem, because everyone you’re competing with does. They either (a) have a book deal big enough that the publishing house devotes a good in-house publicist who is friendly with the top book reviewers, sales people friendly with the best bookstores, etc, or (b) you hire an outside publicist yourself, which plenty of people do, for somewhere between a couple thousand to $200,000 for a full campaign. Private publicists are deep industry secrets hidden from the world, which no one wants to talk about. What, you think Thomas Piketty, famed author and professor at the International Inequalities Institute, doesn’t hire a private publicist for his book Capital and Ideology?

Not that I can blame him—I tried hiring a publicist last minute as I realized how the system actually works, but they weren’t able to overcome the fact that professional book reviewers won’t touch a book unless they’re given at minimum a year’s notice (read that again if you need to). If you’d like to give it a shot, here’s a list of the book publicists you can hire.

I did what I could on my end, e.g., I got Nautilus to publish an excerpt of The Revelations, just like they did for the publication of Richard Powers’ Pulitzer-winning The Overstory, and my in-house publicist eventually convinced the Boston Globe to cover my actual book launch party several months later. So I was far more privileged than most in the grand scheme of things—the reason I emphasize the absence of reviews on release is to showcase how difficult the process is, how many things need to go right, and how publishing’s arcane rules are often impenetrable to outsiders.

So around now is the point where you might be legitimately asking yourself

why write books at all?

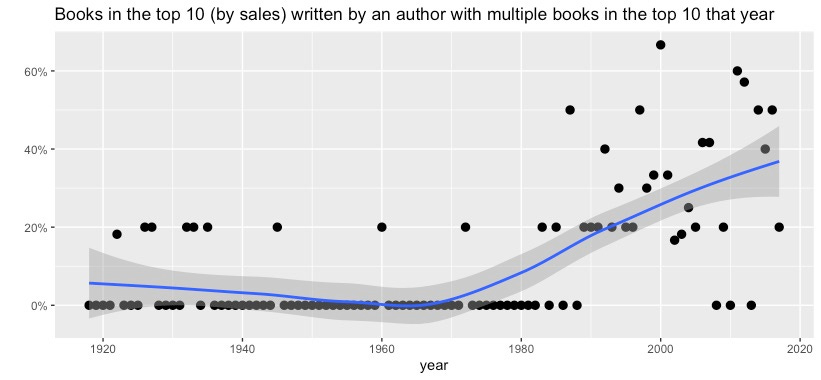

The difficulties of the Hard Steps has a consequence: like everything else in a culture slowly thickening itself with bureaucracy, gatekeepers, and credentialism, books have become the domain of the already-successful. Just as 9/10 of the bestselling movies are now remakes of franchises, bestselling books are now generally by authors who are already successful. This tendency has increased significantly over time:

According to Adam Mastroianni:

In the 1950s, a little over half of the authors in the top 10 had been there before. These days, it’s closer to 75%.

And while there used to be a division in the publishing world between MFA vs. NYC authors, the MFA’s triumph is complete. The new division is MFA writers vs. online writers. And every day I think it slips a little more toward the online camp. Who is most-read essayist writing today? It’s probably someone on Substack. Pick whatever category you like and go run the numbers. When I asked Scott Alexander over at Astral Codex Ten why he’d never published a book, he said (and I’m paraphrasing) there was just no reason to, and from his understanding of the process it looked convoluted and difficult. Correct on both counts.

Online writing is a superstructure growing up over traditional publishing, and will likely one day replace it as the center of gravity. And by the way it’s crazy to even watch myself type that. Because I grew up in a bookstore. I worked in a bookstore for years. I love recommending books, I’m writing a nonfiction book right now I’m super excited about, I’m continuously amazed at how incredible booksellers are. And also, I want to make clear, how incredible members of the publishing industry are, for as individuals they do everything they can to help writers, despite the structural difficulties and opaqueness of the Hard Step model. So let me end with a coda on

the positives of publishing.

Which are significant. Really, despite it all. I was able to make connections with lovely people who fought and died on the hill of this book. I still get emails from readers about how much they loved the book, how they’ve never read anything like it, ever, and asking for another. I have received heart-wrenching handwritten letters. I have done book signings and been treated like a celebrity by bookstore owners. The book might get translated into Chinese. So it’s been incredible, a waking dream. In the end, I’m happy I bullheadedly pursued publication, happy I was lucky enough to squeeze through the multiple Hard Steps (even if I tripped on the last one), and happy that the world has The Revelations in it. I can safely say there’s not another novel like it. It’s the book I wish I had read as I was going into graduate school, as I’ve never seen the experience of science portrayed accurately in literature. My future teenagers will read it (they’ll have to wait, as there are sex scenes), and that means more to me than a million sales.

Occasionally, when remembering something, or needing to make a note, I’ll dip back into the book, and the feeling is of an Eldritch blast from another dimension. Even I don’t understand it completely. It’s like an alien artifact that landed on my lawn and I pawned off the pieces as my own inventions. Some outside force wrote that book, and I suppose that’s all we, as writers, can hope for—to be mere mediums channeling for something else. And, like all mediums, we’re destined to be discarded after use. In the aftermath we must resume the quotidian activities of normal life as if it never happened. We feel as if we once touched the hand of God, but must now go wash the dishes.

Well at least now I have an underpriced hardcover coming to me via Amazon Prime.

Ted Gioia, on his wonderful music blog, has written consistently and convincingly about how record companies have been perversely anti-innovation for thirty years, sticking to slow and outmoded business models while Silicon Valley eats their lunch.

Reading this, I get the same feeling about publishing. From the outside, it looks there are all the pieces needed to make a robust, sustainable book business for the future. But is it being built?