Sorry Ted Chiang, humans aren't very original either

But our margins are still slightly better than AI

At the end of August acclaimed sci-fi author Ted Chiang published an essay “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art” in The New Yorker. Chiang’s argument, that AI mimics what’s already online and therefore must necessarily be unoriginal, led to a huge amount of discussion, receiving millions of views, getting to the top of Hacker News, triggering rebuttals in The Atlantic, etc.

Yet, was Chiang’s essay itself really that different from what had already been written online? I question this because (a) I’ve read similar points before, and (b) I’ve even written similar things.

First, let me give a précis of his argument in full, which goes like this:

(i) AI artistic decisions lack “intentionality” (a hallmark of consciousness, or subjective experience). Since art is fundamentally about communicating experiences and intentions, AI art is an illusion, because AI (presumably) lacks consciousness and intentionality.

(ii) This also has an effect on the technical quality of AI art itself, since AI is forced to either output bland boring averages or simply mimic what's already online or in culture.

Chiang executes his argument about AI’s inability to create art very well, since he’s a great writer. But if you squint at the many previous publications which also made versions of this argument about AI art, sometimes even using similar phraseology, examples, or lines of reasoning, Ted Chiang’s New Yorker piece could be considered a “blurry JPEG” of what was previously online. And so, mostly not too dissimilar from what an AI can do (which continues to improve; just the other day OpenAI released their latest model that makes a bunch of decisions before responding).

This is because human creativity also works by picking ideas already in the cultural ether. And it’s easy to compile a list of articles which make at least some of the same points Chiang does about AI art, like “It’s the Opposite of Art” in The Guardian or “The Problem With AI-Generated Art, Explained” in Forbes or “Is AI Art Really Art?” in Nautilus or “There Is No Such Thing as A.I. Art” in The Free Press.

Funnily enough, one of the closest to Chiang’s essay is my own “AI Art Isn’t Art” from 2022, published shortly after DALL-E 2 arrived and convincing AI-generated images became a reality. It didn’t go as viral as Chiang’s did, but it still got hundreds of thousands of views on Twitter, and it too made it to the top of Hacker News. Of course, our essays are different in structure and phrasing, but they share the same core argument about the lack of communication and intentionality inherent to AI art and its tendency to mimicry.

The most substantial difference is Chiang puts a great deal of weight on how artists must make lots of choices during creation or it doesn’t count as “art.” His argument is that originality involves both the large-scale choices of a piece, but also all the small-scale ones as well, and AI can’t make those choices for you.

I’m less confident that matters. Do all the choices really require so much originality AI can’t ever do it well? Certain choices are obvious extrapolations, almost like an autocomplete. E.g., Chiang opens his essay by describing Roald Dahl’s “The Great Automatic Grammatizator” about the consequences of an invented machine-writer. Yet this reference being used as a lead-in to discuss generative AI already exists in plenty of places: big outlets like Forbes, bloggers, on social media—even AI itself can use it. Chiang’s intro is phrased differently than anyone else’s, but so what?

Again—cultural ether—for you can find the “human artists making choices is the difference” language online as well, e.g., like blogger Steven Sangapore in 2023:

Consciousness must necessarily play a role in both the creation and the consumption of art. Otherwise, there is nothing to communicate. Technological machines running on algorithmic processes do not think, feel or experience. Therefore, they have nothing to communicate about what it is like to be. When making a piece of art, an artist makes aesthetic choices that are, in-part, based on individual psychology and structured value hierarchies.

Or you can find such arguments on social media like Reddit posts. Underneath big viral tweets about AI art you will stumble across replies accusing AI prompting of removing artistic choice and therefore not counting as “art.”

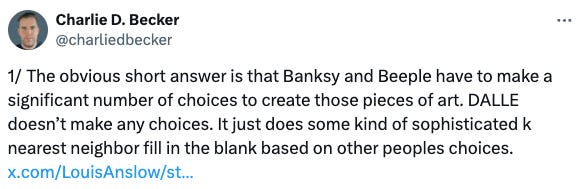

Here’s one I was tagged in (and therefore remembered) saying pretty much exactly what Chiang did regarding this:

My point is not about Ted Chiang at all: it’s that, if we were to judge humans by asking for originality in choices that can’t be described as mostly a remix or mimicry of others, cultural production would collapse, since nothing would pass the bar.

In one of Borges' stories, Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote, the titular Menard attempts to go beyond translation of the famous work by embodying it so greatly that he's able to recreate it accidentally, as if via original thought. In the world of writing, we are all Menards. This is the nature of essays and ideas—to enter the cultural ether, to be duplicated, abstracted, re-written with different verbiage, often made better, until they break-through widely enough to become canon. They are not scientific papers to be cited. Or as Mark Twain already said: “There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope.”

And I’m here to say that’s a good thing.

For years I’ve been worrying about a “semantic apocalypse” where AI produces most of our civilization’s content without any real consciousness, intentionality, or communication.

There’s still a risk of that, and I think there will be many negative effects culturally from this technology as well, but Chiang’s essay, strangely enough, meta enough, is one of the few bright rays of hope I’ve had that human artists will remain. Not because of its content, but by dint of its sheer existence.

Huh? Why? How? What do I mean?

I’m saying that stopping worrying about AI art merely requires the realization that this is how everything already was. 99.9% of our human work was never really original to the degree it couldn’t be described as a kaleidoscopic remix. Not Chiang’s new essay, not my old one then, and not me now either.

And look, the sun still rose today. Cars still passed on the highway. Here in New England, the leaves will change into orange and yellow and then die and come again. An ant makes its way across a playground structure and will trace the same path tomorrow. The magnetic poles of Earth remain unflipped for the last 780,000 years. People still read my writing, even though you could get some of the same ideas from The New Yorker. The revelation that Near Total Unoriginality has been the regime we’ve been living in for a while now is the true take-away here.

Eyes firmly open, we can finally lock gazes with the Grinning Skull of Art: If you squint enough, almost everything mimics or remixes what already existed in culture (or what already exists on the internet). All those famous names of artists and writers you know were not constantly making original choices filled with divine inspiration denied to AI. Much like how Roger Federer won only 54% of points across all the professional matches he played in his life, and is still widely considered the greatest tennis player of all time, if a writer or a thinker can just be slightly more original than their competitors some of the time, then they become one of the artistic greats.

This nihilistic truth of low effective values for human originality leads to an oddly comforting view.

First, to put human artists and writers and thinkers out of a job, AI must win consistently more points than the best humans, who already operate on razor-slim margins of originality, insight, or creativity to begin with (much like Federer’s mere 4% advantage). The average essay is 99.9% unoriginal. A good writer like Ted Chiang might get that down to 90% unoriginal. I don’t think the models can get near that yet, despite producing impressive-by-themselves outputs, because those slim margins are the hard part.

Second, due to various factors like species-bias, distrust of AI, the unsolved unstable nature of longterm AI agenthood, as well as the necessities of audience building, it’s likely that human artists and writers and thinkers will, for the foreseeable future, maintain control of the means of distribution of ideas and creative output. Humans will have sticky control over audiences and the cultural narrative in exactly the way that large publications have a sticky control compared to smaller outlets or individuals.

Those two reasons—slim real creativity margins, and sticky control over distribution—explain why artists and writers (in fact, jobs of many types) have been surprisingly unaffected by AI’s new generative abilities. And I expect this will continue for a while, whether or not those outputs do become close to indistinguishable in quality, whether they’re ever truly original (they probably will be sometimes), and irrespective of whether they are philosophically “art” (due to that pesky lack of subjective experience).

We simply already exist in a world where fantasy books are blurry versions of Tolkien, or a world in which New Yorker essays are blurry versions of Substack essays. So the entire debate doesn’t really matter. Until they become better in a slim-margin business, then lacking the means of distribution and the stickiness of human creators, AI will be forced into the role of tool, not artist replacement.

Saying anything original once in a blue moon was, it turns out, the hardest part all along.

I really like this essay, and I think your point about originality is good. But I’d have two things to add in support of AI art not really being art: first, as you say, getting that last percentage is the hard part. But it’s important to say _why_ it’s so hard: the real innovation in many works of art (broadly defined, including writing and music and so on) is in the subtle ways they break accepted rules and subvert expectations. Definitionally, that’s pretty hard to engineer into something that is essentially a giant interpolation engine that deviates from maximum likelihood based on local statistical fluctuations, particularly since most such violations just read as weird and dumb to the viewer. Second, intentionality matters at least to my mind because it’s a source of human connection across time and distance, e.g. David Foster Wallace died years ago but I can feel his pain and wonder and neuroses when I read infinite jest. Or even in this piece, I read it and wonder about the thought process behind each paragraph and clever turn of phrase. LLMs are lousy for writing long documents as they start to lose the thread after a while, but even once that’s eventually solved, I’d have no interest in reading an LLMs novel no matter how technically skillful. There’s an emptiness there that nothing short of machine consciousness can remedy, and we are nowhere near that (if it’s even possible).

Ironically enough, your same points have been made before by Margaret Boden with the concept of the “superhuman human fallacy”—which posits that the inclination to dismiss AI's creativity because its outputs don't always reach the peak of human creativity overlooks the fact that most humans rarely reach those heights themselves. But to echo your sentiments, I don't think it'll be impossible to find a direct or indirect precursor to Boden's fallacy either.

I personally really resonate with Ben Davis's analysis of AI art in his book "Art in the After-Culture". He touches on a lot of historical currents and the political economy of artistic creation but the one undercurrent that continues to frame my view is that at the end of the day, it's not really about "what art is" but it's about "what we want artists to be".

The "artist" identify is itself constructed and retroactively applied to individuals from our past and through this process of social construction, we have and continue to redefine the identity. AI art threatens that definition more than anything else.

Ben Davis argues that "AI aesthetics" are inherently "prosumer". If I as a consumer want to hear a song that sounds like if Bob Dylan sang for the Beatles, the logic of AI art makes that possible and desirable for me. If I want a novel written based on my own life's events and written in the style of my favourite author, then so be it!

In those examples, the quality and originality of the art object is irrelevant. What is relevant is the power shift they represent. In that future, the "artist" identity could become "producer of art objects that cater to consumer preference" instead of what we currently valorize, which is something along the lines of "someone who reframes our world through their perspective".

Like Hito Steyerl alludes to in her essay "Mean Images", the verb "training" is occurring before and after the creation of the AI output: the training first applies to the AI and then it is applied by the AI after the object is produced. What is important to me is to what extent we allow the logic of AI aesthetics to "train" us into redefining what we want artists to do for us socially.