The internet's "town square" is dead

The ability to control speech always leads to corruption

In hindsight it seems inevitable: a single overarching internet is impossible. The worldviews of people are too fundamentally incompatible at their roots. Or to simplify and put it more bluntly: at least in the United States, there is no way to fit both major political parties onto the same platform and allow them to wield equal power over a perfectly centered Overton window. Blame whichever side you want, red or blue. I’m sure it’s the other side that’s more extreme (and hey, maybe you’re right). But if Twitter was supposed to be the “global town square,” I think Zuckerberg’s so-far successful introduction of its competitor, Threads, which rapidly feels like the other global town square, presages one of the last gasps of the united internet, and the end of an important, if uncomfortable, era. Yes, it was an era of half a billion people crammed into a single echoing room, all our faces smooshed against one another, and all you could taste was the spittle and there was ringing in your ears as the crowd surged. But it was also the time when you could say something and, just occasionally, the entire world would hear it.

Ironically, last month I was begging people to “Stop trying to make a ‘good’ social media site” after the release of Twitter clones like Mastodon, Bluesky, and Notes, and so of course Zuckerberg has to go and release Threads. Within a few days it was closing in on a hundred million subscribers. Zuckerberg gave the standard opening spiel of any social media website, which is that they will focus on “kindness.”

That’s unlikely. As I wrote about the rapidity of the death threats after the honeymoon period on Bluesky:

For a new social media website, going from “omg it’s so great we’re inviting another 5,000 people!” to “we will beat you with hammers” takes about two weeks.

Threads will be no different in that regard, and be the same kind of cancelation-prone endless whirlpool of judgement and gossip that Twitter is. But the success of the new platform is undeniable. Twitter’s recent switch to emphasizing an algorithmic feed, rather than one generated by the people you specifically follow, has turned out to be easily replicated. Threads now looks a lot like Twitter when I log on.

Of course, Threads is still under construction, and importing Instagram users means it is a whole lot more normie, more pop-based, more image-based, and marginally less witty than the classic Twitter crowd. Still, I think it’s going to work in a way no other clone has. And thus, the Twitter obituaries have begun. Where is the global town square now? A triumphal Taylor Lorenz wrote in The Washington Post on Friday night “How Twitter lost its place as the global town square.”

A decade ago, Twitter rose to prominence by casting itself as a “global town square,” a space where anyone could reach millions of people overnight. The platform was pivotal in facilitating large social movements, such as the Arab Spring protests in the Middle East and the Black Lives Matter protests over police violence.

While Meta’s new Threads app is making an impressive debut, most social media experts say TikTok reigns as the new global town square and has held that role for quite a while.

Unfortunately, these social media experts go mostly unnamed and unsourced, which is a shame, since it’s utterly impossible for an algorithmic video-sharing website like TikTok to be a “town square” in the same sense that Twitter was supposed to be. There are all sorts of McLuhan-esque reasons for this: text as a medium is much faster to read, the reply and quote tweet function is what makes Twitter dialogic, its focus on text makes verbal wit the coin of the realm, as well as allowing it to rapidly evolve at near-conversation speed in a way people uploading themselves talking into their phones can’t ever approach. Not to mention how video is an enemy of abstraction to begin with, since so many ideas have no associated visuals. While Gen Z might get their news or information from TikTok, an algorithmic feed of unconnected talking heads taking the place of a “town square” is just. . . impossible. Whatever. Moving on.

I’m sure there will be some sort of narrative pushback about the health of Twitter based on user numbers increasing or hours logged reaching some all-time high, but ultimately there’s no way that the success of Threads isn’t a diminishment of Twitter; if not of its actual user base, then its cultural importance. That is, I think Lorenz is correct that Twitter as the town square of the internet is likely over. But I don’t think there’s going to be one anymore. Instead, we’ll have two, or many Twitters (depending on which you count). And their moderation policies will be different, which affects who is on there, and so affects the vibes of the platform, and, ultimately, this all feeds back into the likely-to-develop overarching political rift between the platforms. To put it very simply: there is a good chance (not an inevitable one, but a good chance) that Threads becomes the “blue” Twitter, while Twitter becomes the “red,” well, Twitter—following the same sort of politicization, red or blue, that has happened to the smaller Twitter clones, and that you can find almost everywhere in our culture.

After all, according to Axios, democratic members of Congress have jumped onto Threads much faster than their republican colleagues. This may be surprising, given that Zuckerberg is not traditionally “blue-coded” over concerns like election interference at Facebook and so on. But advertisers, which Twitter has struggled with under Musk, seem to already understand that Zuckerberg will avoid controversy and play by the Twitter-circa-2020 speech rules. Much like TikTok and Instagram, Threads appears quick to censor anything charged, like discussions about vaccines (so much so that attempts to argue that vaccines are safe have gotten banned on Threads, just for engaging with the subject). Threads may end up smaller, slightly more boring, and a bit more image-based, but with all the advertisers and celebrities and a lot of the journalists.

What makes this all interesting to me is that the story of Twitter the company is really a story about the inevitable overreach that comes with too much power. Controlling speech without a basis in a constitution nor with democratic oversight is an intoxicating ambrosia normally denied to all but Roman emperors and popes. And every time we’ve let someone do it with Twitter they’ve taken it too far and alienated a large portion of their user base. That’s the true story of Twitter: the inability of anyone to handle historical levels of control over speech itself.

The original tale of Twitter’s corrupting power is already well-told: The first group that controlled speech on Twitter was openly blue and did things like banning scientists who argued for the lab leak hypothesis, all the way to choosing what news stories got run in the last frantic days of national elections. That’s why there were more and more red Twitter clones, from Gab to Truth Social. I could go over the details of exactly what the initial group did—you can read through the Twitter Files to see everything—but I think it’s fair to say that, even if you judge claims of their censorship as being overblown, those in charge did not handle their power in a way necessary to preserve faith in the town square.

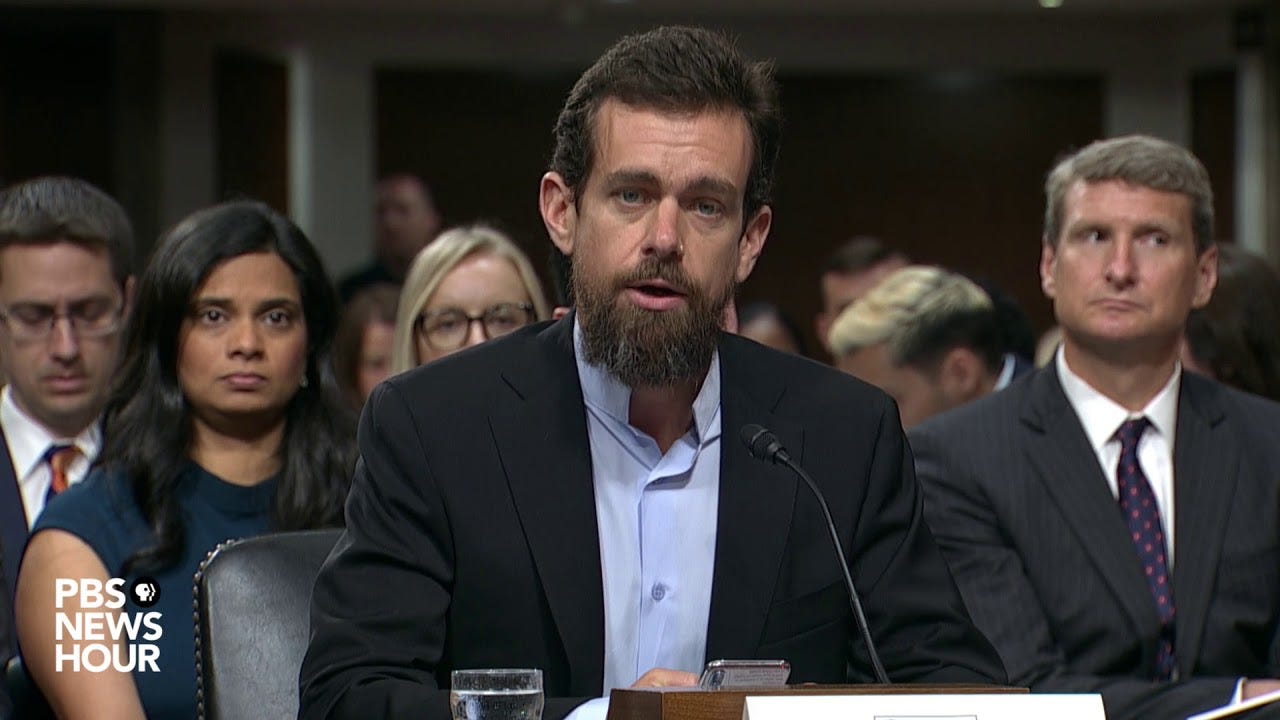

I’ll just give one example: Jack Dorsey went in front of Congress and said Twitter didn’t shadowban people. This is because it turned out Twitter had an internal definition of “shadowbanning” that meant people couldn’t interact with or view your posts at all, rather than you secretly being put on a list that actively downgraded your interaction—which Twitter unequivocally and admittedly did all the time; in fact, they wrote so on their own company blog posts. Within the company they had a “trends blacklist,” a “search blacklist,” and a “Do Not Amplify” tag they applied to whichever accounts they liked and they didn’t inform anyone of it. It’s pretty suspicious when you’re denying culpability by giving a definition of what you’re not doing that would make literally no sense to even implement. If Twitter had implemented its fake definition of “shadowbanning” the shadowbanned account would get zero interaction. Zero likes. Zero replies. Zero retweets. There’s nothing “shadow” about that. It’s just banning, since the user would obviously notice they were tweeting into the void. It’s such an obvious definitional shield to hold up to say we’re not “doing X” when “X” doesn’t even make sense, and it’s exactly the kind of thing that triggered distrust.

Eventually the original Twitter team, which became quite hardened as robust misinformation and censorship teams were formed during Covid, took it far enough to piss off one of the few people who could actually do something about it: the richest man in the world. Who then, in what amounted to a monetary revolution, bought the company and fired 80% of the staff.

And yet, a similar sort of corruption by power occurred under the new ownership. I don’t mean in the terms of the same specifics; e.g., Elon Musk has made a lot of the Twitter algorithm open source, which is commendable. But initial promises of a “content moderation council with widely diverse viewpoints” were canceled after Musk became angry that activists were trying to get companies to stop advertising with Twitter.

Perhaps, at a personal level, Musk himself feels he has kept strict separations between his personal account and opinions, and his role as CEO, but it never appeared that way from the outside. For instance, surely Musk could have reopened the Overton window of what’s acceptable speech on Twitter without making it so that when journalists query the Twitter Press office they get an automated reply of a poop emoji. If you send poop emojis to journalists, it’s totally unsurprising those same journalists are going to accuse you of bias when you apply “state-funded media” badges for the BBC and NPR accounts—even if those organizations really do get a percentage of their funding from the state.

It’s this kind of unforced error that cropped up again and again under his tenure. Rather than simply rehashing the blue check verification system, he totally upended it, making it pay-only, which fundamentally shifted the politics of Twitter since the badges themselves became support or refusal identifiers for Musk’s policies. A huge portion of users saw the blue check deconstruction as him having his thumb on the scale. Meanwhile, he got in constant Twitter battles with upset celebrities (who are now happily migrating to Threads). He handed Substack writers the “Twitter Files” and, just weeks later, banned all interaction with the links to those writers because he was mad at Substack for releasing a (tiny in comparison to Threads) Twitter competitor called Notes. In fact, Musk’s Substack nuke is ongoing—links to Substack posts like this one are still, many writers say, suspiciously low on engagement compared to before his tenure, and you can’t embed Tweets into Substacks, nor get image previews to show up for a lot of Substacks. I guess writers are marginally hamstrung forever now, simply because Musk was mad once. Another example: last month, Musk announced calling someone “cis” or “cisgender” is a punishable offense on Twitter, which, even if you have a very low opinion of those terms, squares at best uneasily with the fact you can say a lot of really crazy and extremely mean things on Twitter without much consequence. And Musk himself personally declared for the red team and did a bunch of signal-boosting, like the (somewhat disastrous) DeSantis announcement.

At this point, I should say I’m well aware that there’s no perfect way to run a social media company. There is no actually fair “town square”—it doesn’t exist. It’s a dream. Somewhere, someone makes decisions about what’s on and off the platform, and that will not please everyone, and it will always be controversial and favor one side more than the other to some degree. Obviously. Also, the people in charge will naturally have some political leanings. Obviously. But the appearance of fairness by the leadership, just a little bit of whataboutism, just a little bit of attempted neutrality, is necessary for trust. Imagine the reactions if Jack Dorsey had been constantly retweeting accounts named like @radfeministsforwealthredistribution or something—to what degree would you trust that person to then cleanly separate their role as a CEO from their role as a public person and manage a “town square” fairly? By his own standard of what he wanted to accomplish, Elon Musk was unwilling to give up his own freedom of speech to save that of others.

Witnessing all this, and seeing an opportunity, Meta started work on Threads only in January of this year. I know some people think Musk is stupid and doesn’t actually do anything at his numerous monumentally successful companies, and those same people will assuredly take the failings of Twitter under Musk as proof of that. But I think that’s the wrong view. It’s impossible to watch Musk give a tour of a SpaceX facility and answer complicated impromptu questions about aerospace engineering and not believe that he is the central overseer of the best rockets in the world. He’s a great engineer. Others will say he mishandled Twitter because he’s good with companies that do things with atoms but not bits—but PayPal sure seems like a successful “bit” company to me.

Ultimately, I think Musk has had trouble for the same reasons as his predecessors: because the ambrosia of controlling speech is so intoxicatingly strong. All you need do is put your finger on the scale just a littttttle bit, shift how the whole thing works just marginally, and you can literally steer the culture. The omnipresent reactivity (followed by backtracking) during Musk’s tenure attests to this. Mastodon links are banned, no wait, go back! Substack links are banned, no wait, go back! Censoring me and other Substack writers was not, I think, part of a grand strategy on Musk’s end. It was a reaction. The exact same way banning the Hunter Biden laptop story because it was “misinformation” was a panicked reaction. Because it’s so easy, you see? All it takes is a tiny bit of code, and therefore the temptation to punish the upstart little company, or make sure a damaging story you can’t confirm doesn’t shift a national election, was just too great for the owners of these platforms.

What I’m trying to say is that the dream of the internet’s bipartisan “town square” is ending, transforming into many town squares tucked in alleys and behind buildings, because the actors in charge couldn’t stop seesawing in terms of who held the power, and because they always took that power too far or didn’t consider how carefully they would have to move to avoid (at minimum) the appearance of bias. If the original Twitter crew had been about 30% less overtly willing to censor news, language, people, or ideas they didn’t like, Musk probably wouldn’t have bought the company, and the blues would still be in control of Twitter and Twitter would still look a lot like it did. And if Musk had not wanted to completely overthrow the blue check system that had dominated the information flows on Twitter and instead merely expanded what was an opaque aristocracy into an actually transparent system of verification for users past a certain threshold of engagement, and also not pissed off a lot of the blue user base personally with his own tweets, nor exercised power in ways that were obviously reactive and personal, then he could have allowed the reds to thrive on an unshackled Twitter without corporate rivals constantly rearing larger and larger heads.

How many stories can you find of a corrupt republic being replaced by a supposedly benevolent dictator, and what happens after? I think it’s rather fitting that Twitter, the greatest engine for controlling thought ever created, is a morality tale. Lord Acton’s ghost appears, all decked out in 19-century garb, digitally remastered, and speaks his famous phrase in poltergeist tones:

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

Or maybe he threads it. Stitches it? No, that’s not quite right.

Posts it. Yeah, he’d post it. Twice. Once on each platform.

This is so well worded. Love it. This line is the perfect summary of the Musk-Twitter debacle:

"Elon Musk was unwilling to give up his own freedom of speech to save that of others."

Whenever I read about the death of twitter, I wonder to what extent this is an American/elite and elite-adjacent death, but not an overall death. Are all the small sub-twitters (car/sports/hobbies/industries) also wholesale abandoning the platform? I don’t see evidence of this in these communities that I follow. This will sound trite, but I have an almost “who cares” attitude about red and blue twitter spaces being divided and separated by platforms. They were always echo chambers to begin with - pulling their most extreme content from other sources and then amplifying for their audiences there.