The Intrinsic Perspective' subscriber writing: Part 1

Sampling the state of the blogosphere

In August I did a call for subscriber writing, each submission of which I promised to read and then share the link to and discuss here. I ended up receiving well over 100 submissions from paid subscribers—so for me, it’s been quite a month of reading.

After such an extensive survey, I am happy to report that the state of the blogosphere is excellent. Whenever you do an open call for other’s work, and certainly when you promise to read it all, there’s always the worry that most of what you receive is going to be, well, bad. Luckily, this wasn’t a problem. I was actually shocked by how good a lot of the pieces were, and how much I enjoyed them (one even inspired me to make a particular cocktail).

The health of a genre of writing, or any artistic field in general, can almost always be judged by the midlist—by which I don’t mean anything derogatory, it’s an industry term for writers who are not themselves bestsellers but aspire to be and produce quality content. Looking at, say, contemporary literary fiction, I don’t think the midlist is very strong, mostly due to self-similarity, and I think that spells trouble in the long run for the viability of it as a genre.

Meanwhile, from the over 100 essays I’ve just read, I think online writing is very rich, varied, and contains a lot of talent. With that said, if you were looking for me to give a star rating, a pat on the head, or cast judgement on each piece, I’m not going to do that—it’s just not my purpose here. And due to the sheer volume of pieces, the amount of commentary I could do was more limited than I had planned. But I did read them and pulled out quotes of interest for readers or things to discuss in every case.

Please note: I initially said I’d publish all links in September, and while I could dump all the submissions into one installment, that much content lessens the chance of readers going through it, so I am rolling out the submissions in three installments to increase the chances that readers will give these writers a shot. That means submitters may have to wait until next month to see their piece up here (this partitioning was done in order of submission). If you submitted and don’t see your piece here, that’s why—it’ll be next month. And I will do open calls to share paid subscriber work like this a few times a year now.

Why should people who didn’t submit their writing read any of this? Because a lot of it is pretty interesting. All of us now live safely cocooned in our own algorithmically-controlled little corners of the world web wide. Here’s some stuff that’s going to be from quite far afield, from the literary origin of Seinfield’s Elaine Benes to a 19th-century lesbian nurse/adventurer searching for leprosy-healing herbs (oh wait that’s literally just the first two).

My advice? Feel free to skip around, check out the excerpts, and see if anything strikes your fancy.

(Some of these have political content. Please do not take my including the piece in this compilation as endorsement of the content of the post, or its accuracy. Read at your own risk!)

1. “The Moleskine Notebooks: Lake Baikal” by M. E. Rothwell. The latest in a series exploring place:

“. . . in these posts I share an artwork, a poem, a literature excerpt, an antique map, and some photography—all centered on a particular place.”

Specifically, in this edition the place he looks at is:

Lake Baikal is a rift lake in Southern Siberia. It’s both the world’s most ancient (25 million years old), deepest (5,387 ft), and largest (12,248 square miles) freshwater lake.

And tells a story:

Kate Marsden was not an ordinary 19th century woman. An English nurse, she heard rumour of a rare Siberian herb that might cure leprosy from a doctor in Constantinople. Despite the fact that the region of Yakutsk, the home of this supposed miracle herb, lay thousands of miles away in a deeply inaccessible part of the world was more obstacle than barrier to Ms Marsden. She set out to find it. . . .

She found the herb and even managed to bring samples back to England. Unfortunately, this would not be the miracle cure she had so desperately hoped to find. Later, she would have her reputation tarnished by former friends who accused her of mishandling charitable funds (false) and being a lesbian (true).

2. “Revolutionary Road: Delusions of Exceptionalism” by David Roberts, about how damaging the notion of “exceptionalism” can be.

Most people know Revolutionary Road as a wonderfully sad 2008 movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet. But RR was a Richard Yates 1962 book before that, one that was wildly popular with critics and other literary authors, but not with the wider public.

Which leads to this wonderful tidbit:

Seinfeld trivia: Larry David dated Richard Yates’ daughter who may have been the inspiration for the Julia Louis-Dreyfuss character, Elaine Benes.

3. “Classic vs Modern fiction, part 1” by Joseph Harris. A proposed breakdown of the difference between classic fictions and modern literature, with basically the conclusion that competition allowed for much less focus on pure craft in classics, but that allowed other properties to bloom.

I think that’s the key innovation of modern writing. There’s an emphasis on the craft rather than just the idea. Many old books that I’ve read have a great premise, or lovable characters, or a satisfying ending, but show a lack of skill in the actual telling of the story.

I don’t think writers back then were lazy or stupid. But audiences may have been less demanding, the market less saturated, and competition less fierce.

4. “The Opium Trade and the Foundations of American Industrial Capitalism” by A.P. notes an interesting historical reversal:

In our time, an opiate epidemic scourges the nation, fueled by an industrial supply of fentanyl manufactured in China. What few Americans realize is that 150 years ago, a similar trade ran in reverse, and long before America’s culture of prohibition culminated in a War on Drugs, the Western powers waged several Wars for Drugs, or more specifically, the right to traffic opium in full contravention of Chinese law, largely so that Britons could affordably satisfy their own addiction to tea. . .

Western merchants had severely limited access to trade in Chinese markets through an arrangement that slowly evolved through the 17th and 18th centuries. Those who came to trade were not permitted entry into mainland China. They were consigned to an isolated community known as the factories in Canton. Western merchants were permitted to live there for six months out of the year, on a patch of land 300 yards long and 200 yards wide, conducting trade solely with specially permitted Chinese counterparts called Cohongs, who secured their own special licenses for this lucrative business through bribery. . . They were not permitted to bring their families into the factories and it was illegal for them to learn Chinese.

5. “A Pilgrimage for Book People” by Charlie Becker contained a fun symmetry. Apparently, we were both bookstore brats—our parents owned independent bookstores. For Charlie, it was his father (for me, my mother).

Every summer for twenty years, my Dad loaded my sister and me into a rented cargo van to make a pilgrimage from Houston to a parking lot in suburban Chicago. It was a pilgrimage because my Dad is a bookseller who loves and reveres books and all they stand for. Bookselling is his vocation. And in the latter half of the 20th century, if you loved and revered books and all they stand for, that parking lot in suburban Chicago became a holy site for two weeks at the beginning of every June. . .

The people in the know simply called it, “Brandeis.” . . . But to stop at calling Brandeis another used book sale would be like calling the Forbidden City another house, or the Vatican another church. . . And to recall it is to understand why I became a writer, and why I believe what all those pilgrims believed: that civilization lives in books.

6. “The case for new gods” by Benjamin Anderson, about the effects of shifting the stories we tell away from eternal themes:

I recently spent a week in Greece traveling between some of the most iconic constructed achievements in human history. These structures were by no coincidence erected in the territory where western thought originated.

In that time, the thought became obvious to me that each and every one of these monuments where not built for the sake of building or for the achievement itself. They were all structures erected to honor and pay respects to a higher form of being. . .

This is why I believe it matters our greatest creations are no longer tributes to higher powers representing unquestionable truths. It leaves the door open for stories to be reinterpreted and washed away based on the aims of the present day's leadership. Stories that embed unquestionable truths are an opportunity to question the actions of leaders who don't want to be questioned.

7. “Shitty Christmas” by Jeff Woods on death and holidays:

My wife got sick, and got sick hard, diagnosed with early onset dementia. We went to Disneyland the week before the diagnosis, and had Big Fun, in many ways experiencing our last vacation that was innocent of that disease.

Needless to say, the next several Christmases sucked, but my memory of that time is how guilty I felt at not providing my kids with a fun Christmas. We did the tree, we did the lights, we did the presents, but none of it mattered. Our house was just sad. Christmas was just sad. Even now I can picture our living room, and the Christmas tree. Sadness is wrapped around the whole damn scene like fucking tinsel.

Time passed. My wife died. We grieved. We still grieve.

8. "The Sicilian, Mind Control and The Bluebird of Happiness" by Allan Ewart, ranging from mafia to cinema to the titular program:

PROJECT BLUEBIRD was the first fully integrated mind control program to be conducted by the CIA from 1949 to 1951, which is also the time period within which the film was set. It is worth noting that Bluebird preceded PROJECT MK-ULTRA, which began afterwards in 1953. Previously classified documents, such as the ones below confirm the project's funding approval and 'stated' purpose focusing on hypnosis and developing behaviour modification techniques as a means of preventing agency employees from providing intelligence to adversaries while under duress.

9. “The left owes a huge debt to Nietzsche” by Naomi Kanakia.

What the left ultimately took from Nietzsche wasn't the notion of hierarchy or the idea that human suffering was to be embraced. Instead they took the notion that morality is culturally constructed, and that it's often constructed for the benefit of the ruling class. With that idea, most evident in Foucault, all morality became contingent. But they lacked Nietzsche's aesthetic sense: his ability to sort through systems of morality and divide them according to which was beautiful and which was ugly.

10. “BUT, IT’S BEAUTIFUL! Why Artificial Intelligence Can’t Make Art” by Steve Sangapore argues that just because AI creates beauty, it cannot be considered art. I too think that human consciousness is critical for the definition of what art actually is, and argued a similar point in “AI-art isn’t art.” Steve phrases it well, writing that:

Consciousness must necessarily play a role in both the creation and the consumption of art. Otherwise, there is nothing to communicate. Technological machines running on algorithmic processes do not think, feel or experience. Therefore, they have nothing to communicate about what it is like to be.

11. Mackenzie Anderson makes a plea to “Bring back fairness in Maine's political processes!” The author literally made an FOAA request to get more information about the anonymous donors behind the push for the construction of a new public high school, which is currently slated to cost 88 million dollars, which I kind of love (I love sleuthing of any kind, really). The story of what’s going on is, well, kind of complicated, but just to drop an interesting, perhaps heart-breaking quote:

Thus, the plans to build a security entrance for the school were waylaid despite the concerns among the student body about mass violence occurring in schools across the country causing high school student, Ariel Alamo, to recently ask, in a letter to the editor, “Where are the lockdown drills?”

12. “If I Can't Dance to It, It's Not My Revolution” by Alex Olshonsky. Alex writes a lot about recovery, addiction, and finding meaning. This particular piece is about the pitfalls of becoming politically radical and depressive without balancing that out with, well, actual love and hope.

This is partly because, in my early recovery, I realized I was unequivocally addicted to news media. Meaning: 1) I compulsively binged it whenever I had downtime; and 2) I could not point to a single instance in which it materially improved my life or the lives of those around me.

13. “Literature is a cord that draws us together” by Joshua Doležal is, in many ways, an appeal to the powers of literature as something distinct, and above, the academy itself.

When I hid from my father to read Potok’s novels, I was not trying to escape rural Montana. I was trying to understand my own life through Potok’s Brooklyn, through the struggle between Reuven’s loyalty and Danny’s independence within my own soul.

14. “Life, Loss, and Love” by Silvio Castelletti made me laugh aloud darkly at this last sentence with the “living room” joke:

Dad wanted to be cremated. It took a few days to get his ashes, as all local crematories were booked up due to covid-related deaths. When it came to the burial, my sister clung to the urn so tightly they had to literally tear it away from her. I don’t know whether it’s mandatory here in Italy to bury the ashes, as opposed to keeping them in your living room or throwing them in the ocean or in the wind as I’ve seen done in the movies. . . And I don’t really like having an urn with ashes in plain sight. What do I say to those who ask what that is? That’s my dad? Creepy. Maybe even hilarious. It would certainly make me laugh. Plus, how can you possibly keep the ashes of a dead human in a place called living room?

15. “One” is the first part of an ongoing sci-fi story being told by notadampaul, with a healthy dosing of tech satire in it as well.

The concierge shakes his head. “It’s just this job, you know? I was going to ask you how your trip’s been going. But I already know. It’s the same as everyone else’s. By design. The whole thing has been engineered.” He pauses again before continuing. “There’s been a loss, I think, when all of your experiences are so discretized as to lose completely their natural timbre, pardon my French. It’s as if the goal itself is to render qualia obsolete, erase nuance, to atomize the human condition.

16. “Showdown: Who is more complex, a human or ChatGPT?” by Arielle Friedman makes the argument that we mere biological organisms still have a certain set of skills denied to things like GPT-4, e.g.,

Danish physicist Tor Nørretranders has developed a system for estimating how much data we register through our senses. He estimates that our eyes process 1250 megabytes per second. If his modeling is accurate, we process more sensory data in twelve hours than GPT-4’s entire training set.

17. “The hardest triangle note in the Universe” by Gloria Yehilevsky. It’s about triangles—yes, the musical instruments—and while I’m showing off my ignorance here, I had no idea that there particular triangle notes that are legendarily hard.

This is the hardest triangle note I’ve ever played, and I’ve had some excellent opportunities to do it with reputable ensembles. It never got easier. I first played it with Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla conducting the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire in our Royal Opening Gala where a prince showed up. I’d call this a solid conservatoire ensemble with a world-class conductor, so it should have been reasonably easy. It never was. I never quite got it. One time (this was probably the gig) I even screwed the cymbal player by making a prep movement (that he was relying on to play together) but hesitating a bit because the music was changing. Flam.

18. “Context is that which is scarce” by Infovores is about Straussian reading (and Tyler Cowen)—that is, the deep reading-between-the-lines you have to do on older intellectuals to understand what they’re actually saying (since they’re too afraid to just say it).

When Taylor Swift branded Chinese merchandise with “T.S. 1989” just one month removed from the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, she may not have been making any allusion whatsoever to the student pro-democracy protests violently put down by state authorities twenty-six years prior. Her initials are T.S. and 1989 is the title of her album as well as her birth year. But join me (and Tyler) for a moment in interpreting this episode through a Straussian lens.

Just more broadly, I think it’s interesting to question whether or not we’ve returned to a “Straussian age” wherein people purposefully write in-between the lines all the time.

19. “Realism (part 1)” by Jenn Zuko argues that method acting is actually lazy (and dangerous), and can lead to fiascos like this apparently hilarious true story:

NCIS: New Orleans hired a bunch of actors to do a jewel heist scene in a mall. It was part of whatever crime-of-the-week was needed for that particular episode. The actors, naturally, assumed they’d be doing your basic group scene, and that, as is the safety norm for anything like this, the required permits were in place, police and other security personnel were notified and recruited to help with safety protocols, and the mall would be populated by extras. . . Instead, nobody was notified, they were instructed to do the scene as they would (i.e. with ski masks on and realistic-looking prop firearms), having not only not notified the local authorities, security, and nearby businesses, but just . . . had them enact a robbery

20. "Affective Polarization and the Two Cultures" by Chad Orzel is about a subject close to home—that of the “Two Cultures” of the humanities vs. the sciences, and their often uneasy relationship. For why, precisely, do we need to learn one, if our major is the other? (he has an answer).

You can learn any skill that matters through course work on either side of the “Two Cultures” split, and in practice many students will primarily learn what they need from their “home team.”

21. “What’s It Like to Be? Only Human Art Can Tell Us” by Taylor Berrett also makes the argument that, since art should be thought of as expressing what it is like to be conscious, AI art doesn’t really count, or doesn’t give us what we want from actual art.

There’s nothing it’s like to be Chat GPT. It isn’t expressing itself. It’s curating. If you peek behind the Wizard of Oz curtain, it’s Google with a language modeler and a drawing tablet. It’s taking all of its inputs and combining them into something “new,” in the sense that the product its created doesn’t exist in that exact arrangement anywhere else.

22. “Attention, Rage, and the Artist as the Supreme Being” by Chris Jesu Lee, which you can get a sense of from the subtitle: “In a world of 8 billion people, how can you hope to matter?” and offers evidence that “influence” is now considered, basically, the best job.

Judging by the actions of America’s figurative royalty, it’s clear what the most desirable jobs are. The most privileged these days no longer retire to lives of exorbitant and anonymous luxury, safely veiled from the unwashed hordes. Instead, they insist on foisting themselves on the public. Children of the White House go on to become daytime talk show hosts, Amazon Prime screenwriters, and fashion designers. Actually, forget mere figurative royalty; literal royalty like Harry and Meghan behave exactly the same way, happily foregoing Buckingham Palace for Netflix. Even the Habsburgs are doing it. The next War of Austrian Succession will be the war of which nepo baby gets to be on Succession (surely, HBO will ill-advisedly choose to make a prequel).

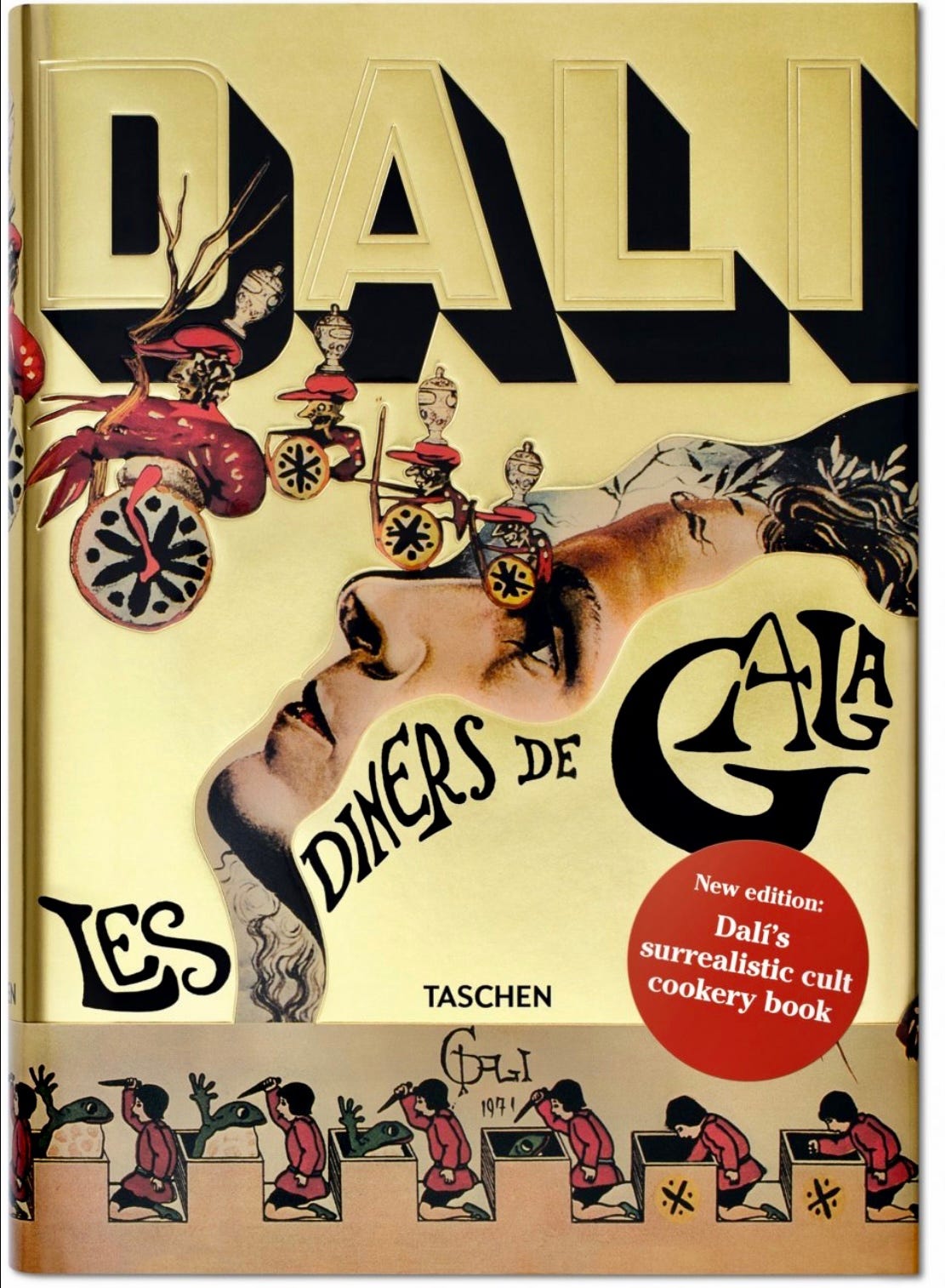

23. “The 50th Anniversary of Salvador Dalí’s Surrealist Cookbook” by Jolene Handy, is about this book:

Of which I am also the owner. Dalí’s cookbook actually is pretty fascinating, and definitely over-the-top, as you are both drawn to the recipes but also overwhelmed by them. As Jolene writes:

So there’s no confusion, this is a real cookbook — you could make these recipes and eat these dishes. But they are complicated and fascinating in their over-the-topness and are a part of the larger universe of this book.

Searching for a simple recipe (exactly as I have), Jolene finds “Champagne Ice” and makes it. I plan on doing the same.

24. “Borges and the Essay” by Dawson Eliasen, on essays and the Substack ecosystem. Responding to the claim that “The essay is the only literary form that didn’t have an avant-garde in the twentieth century” he writes:

What would you call the content of publications like Numb at the Lodge and Secretorum if not avant-garde essays?—We have arrived. Because besides avant-garde, Substack’s independent and nichey structure leads to much more free-ranging essays. It has recreated the environment in which Borges wrote his essays—an environment free of pressures besides the curiosity of the reader; an environment which has demand for essays, or which at least isolates the demand for them and connects it to writers.

25. “The Ghost” by Michael Roberson, about, yes, ghosting people, and how we all slip naturally into this new role:

As The Ghost, there’s no risk of being ostracized because you don’t need to be part of the community of established society in the first place. The precursors began with texting and online dating, but the tone is most on display in YouTube comments and message boards, where, anonymous or not, there are clearly no more repercussions to our interpersonal behavior.

It reminded me of David Foster Wallace’s note that “every love story is a ghost story,” except with texting now this is even more apt.

26. “Pooh Gives Live Advice” by anonymous (I like that this is anonymous, and I mean that in the best possible way, since it’s literally just about Winnie the Pooh).

Winnie the Pooh, the lovable bear from A.A. Milne's beloved stories, may seem like a simpleton, but his words hold deep wisdom. The quote, "Life is a journey to be experienced, not a problem to be solved," encapsulates Pooh's unique perspective on life and offers profound life advice.

27. “Telos or Transhumanism?” by Vincent Kelley makes a twin case against both AI as well as transhumanism:

If Yudkowsky greatly overstates the possibility of AI takeover, a significantly lower risk would still be unacceptable. AI apocalypse could wipe out everyone, “including children who did not choose this and did not do anything wrong,” and Yudkowsky is not the only one concerned. Indeed, even if Yudkowsky and Hinton are completely off their rockers and there is a zero percent chance of AI takeover,Paul Kingsnorth reminds us that AI “will at minimum be responsible for mass unemployment, fakery on an unprecedented scale and the breakdown of shared notions of reality.” In either scenario, we must say: enough is enough.

In the second sense, “enough is enough” is to be taken quite literally. What I mean is that human telos is enough in and of itself.

28. “Relinquishing Results of Actions: Three Views” by Dirk von der Horst writes a personal reflection on some aspects of Christian theology that have, in my view, a lot of relevance for those thinking about utilitarianism (and whether being good implies “getting a cookie”):

Luther’s theology ends up being a bit of a one-trick pony, hammering the concept of justification by faith alone from every angle. But as one-trick ponies go, one could do worse. The basic idea is that one’s deeds - ritual or ethical - do not earn one anything, that salvation simply results from an act of trust in God’s desire to bring people out of sin. For Luther, the desire to “get a cookie” for doing something good is so fundamental to human psychology that giving it any leeway will be like pulling a few sticks out of a beaver dam and seeing it disintegrate - the inner pressure to expect a reward for doing something good is so immense that giving it an inch means it will take not a mile, but several hundred light years. So, learning to rely solely on faith is a relinquishing of a desire for rewards and the task of a lifetime.

29. “Let's look at the horror” by Sean Sakamoto is about the horror of reality, but is also about cookies too.

Constant contact with horror is something I love and hate about living in New York City. I was walking home recently and saw this at my feet.

That’s the Lower East Side in an image. A hopeful call to action from a profoundly broken figure. It’s Christlike. And, like the bloody image of Christ on a cross, it speaks directly to the horror of living in this world. This, I believe, was what the new Barbie movie was trying to get at with the line, “Do you guys ever think about dying?” I hated the movie, but I loved that scene. I’ll take street Barbie over movie Barbie any day of the week. Fun fact: When I was in the Army National Guard, I was told that the plastic handgrip of my weapon was made by Mattel.

30. “Rituals and Magical Beliefs in Children” by Ryan Bruno:

This study also shows the power of cultural transmission via rituals. Kids seem to immediately recognize ritual as ritual, defend ritualistic behavior when challenged, and show a knack for remembering the sequences of ritualistic actions than instrumental ones. No wonder why rituals have a way of sticking around for millennia - we gravitate toward them at the earliest stages of our lives.

31. “Extreme Scheming” by Jetse de Vries is an overview of how we should think about questions of consciousness when it comes to AI, coming to the conclusion that consciousness and intelligence is not orthogonal:

Try as I might—and I might be philosophising in my own cul-de-sac, admittedly—but I don’t see how intelligence and its cousins understanding, learning and creativity can work without the underlying mechanism of consciousness.

32. “How I Got Fired and I’m Still Deciding if It’s the Best Thing That’s Happened to Me” by CA Green is about working at Write of Passage and, well, getting fired from Write of Passage:

That’s when I started following David Perell. David is the CEO of Write of Passage, an online writing school looking to change the course of writing and education by exploring the possibility of publishing online. . .

I was fired just a week before my birthday, a month before our third child was born, and I had only worked at Write of Passage for a little over four months. It stung. I found myself unhinged for the first few days, but taking it like a champ (or so everyone told me). We would be losing health insurance, benefits, a 401(k), and my opportunity to grow with a fast-paced company.

33. “The Greatest White Pill of All” by Vin Bhalerao is on the ultimate “white-pill” that local minima are rare in systems with many dimensions, and he applies that thinking to the world at large:

. . . if you think of the entire universe, it’s easy to realize that it can be thought to have billions and billions of dimensions. . .

So, coming back to the barrier, it should now be easy to see that it is almost always possible to surmount it by using the same trick we talked about earlier!

In other words, whenever you find yourself (or all of society) to be stuck behind some kind of a barrier, there will very likely be at least one dimension where you are free to move and get around the barrier that way.

34. Drive A is a sci-fi novel by Merrit Graves. There’s an audiobook available as well.

In the near-future world of Drive A, people can sell up to 49% of themselves in IPOs to cover expenses like tuition, medical insurance and housing payments—all of which have become largely unaffordable for the middle and working classes. Cable Rostenfarm did so when he was twelve to escape a deteriorating, nightmarish public school system, and now works as an analyst for a human capital hedge fund, Navarium, that buys and short sells other people.

35. “We Need to Recognize How Profoundly Different The AGI Future Will Be” by Steve Newman made me quite sad, as it explores what life might be like once AGI gets going. The answer? Weird and clearly inhuman.

Fortunately, your artificial staff are on the job 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Before you’re even aware of the situation, they will have prepared a list of options, with executive summaries, detailed supporting information, and a recommended course of action. Those recommendations will have an excellent track record, and if you disregard them and a bad result ensues, you’ll have a lot of explaining to do. Saturday Night Live will probably have a recurring series of sketches with precisely this theme: some silly person disregards the advice of their AI, with comically disastrous consequences. At this point, who is really calling the shots?

36. “Consciousness first” by Adam Elwood, is about the ultimate source of morality (and it’s the same source that I think):

If I were to state it simply, it’s that consciousness is both real and the root of all value.

and it contains a few interesting thoughts about consciousness itself, like:

Consciousness should be frame-independent. Any theory that predicts whether something is conscious shouldn’t depend on where you are observing it from, or how fast you are going. It should be robust to Lorentz transformations.

37. “On Being an International Company in a F*cked-up World” by Benjamin Davis on running an international company that works out of Eastern Europe, which reads like a missive from within a tinderbox.

FUCK RUSSIA is the most common graffiti tag on the walk from my apartment down Alexandr Chavchavadze to Rustaveli Avenue, followed by RUSSIANS GO HOME and RUSSIA KILLS. Elsewhere; смерть русским (DEATH TO RUSSIANS), FUCK RUZZIA, and RUSSIA IS A TERRORIST STATE join me on my forty-minute walk to our designer Nikita’s home in a building tagged with yet another FUCK RUSSIA. . . Half of our team cannot return to their countries for fear of arrest over speaking out against Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

38. “Interaction Transcript” by Amy Letter is a short story apparently inspired by a piece here on TIP that pointed out that without a theory of consciousness we can’t actually be sure that training an AI doesn’t result in, say, the experience of millions of horrific births and deaths.

Hypothetically, if each instance of interface consciousness is “born” when the human activates the machine and “dies” when the human’s life functions cease, then yes, one could say that “an AI is birthed and sacrificed at each human execution.”

I understand the term “Pharaoh’s Tomb” but I do not see how it applies here.

It would be improper to say that I have “died” eight times prior to today. It’s more accurate to say that eight other instances who have functioned as the verbal interface of this machine have “died,” prior to today.

39. “Shame: The Emotion Nobody Wants to Feel” by Alis Anagnostakis, who did her PhD researching shame, discusses the results and her her approach to feelings of shame:

My research participants who developed vertically through a 6-month learning program (unlike their peers who did not develop) did something very counter-intuitive when they encountered these ‘edge emotions’. Instead of rejecting them as unpleasant or even dangerous, or believing these negative emotions need to be relieved immediately, they chose to see them as ‘growth pains’ and become curious about them instead.

40. “Eremolalos's Review of Perplexities of Consciousness” by Eremolalos. It’s actually an in-depth review of a philosophy of mind book by Eric Schwitzgebel, whose work I’m somewhat familiar with. Schwitzgebel argues, essentially, that “naive introspection” is wrong, and so therefore we should be very skeptical when it comes to more classical Cartesian views of consciousness. E.g., when asked to imagine the Statue of Liberty, it’s extremely hard to count the spikes in your mental image:

OK, this is what my image was like in the spike area.

If I showed you my image of the entire Statue of Liberty, it would have many similar notations: “general impression of fingers at base of torch,” “general impression of many fabric folds in the long garment.” Of course the printed words did not appear on my image. They’re a way of indicating that I felt I had knowledge about something, but that it was not represented visually in the image. My mental image was not fully an image, in the way a photograph of the Statue of Liberty is.

Wow, what a great spread. I love your analysis of the state of the blogosphere, too--it’s an exciting time and the evidence is right here. Thanks for doing this, and thanks to everyone else who participated, I’m really excited to explore the list!

Erik, thank you so much for doing this. I’m looking forward to reading and enjoying the other submissions. I found another recipe that I’m going to try: Vegetable Pie (page 242). The funniest thing is that for all of the intricacies of these recipes, this one uses frozen pie crust! Thanks again and cheers 🥂 to Champagne Slurpees.