The riot in Toronto

An excerpt from The Revelations

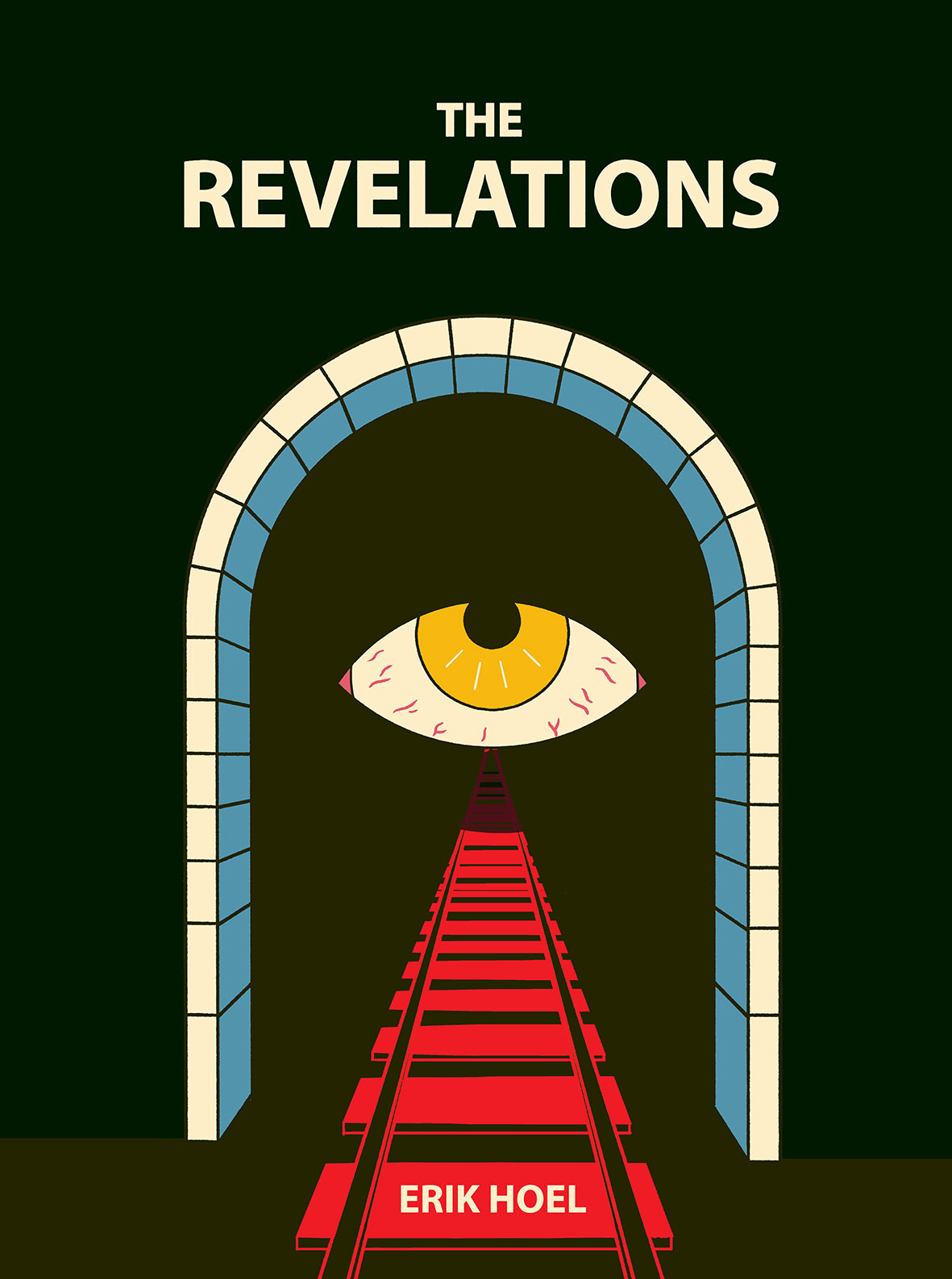

Alexander Naughton, the artist for this Substack, took it upon himself to create a mock-up of the cover he would have done for my novel, The Revelations. I loved it and wanted to show it off, so what follows is a self-contained excerpt from the book.

IN THE SUMMER after they graduated from college, Kierk and Mike—friends, classmates, and intellectual competitors in many late-night dorm-room debates—had gotten into Mike’s messy jeep with their science poster, “Neural correlates of bistable perception,” secure in a plastic tube rolling around in the back. Together they had road-tripped up from Amherst, Massachusetts, to Toronto, Canada, so that they could present their poster at the 14th annual meeting of the Association for the Scientific Study of Consciousness, held by some clerical error on the exact same weekend and only blocks away from the main site of the G20 economic summit. As they drove, around them a legion of other cars bore protesters heading to the economic summit, protesters who were equipping themselves with an armament of balloons filled with paint, who had signs clanking around in their trunks instead of science posters, who were listening to radical podcasts and communicating to one another via encrypted text messages. The occupants in the thousand cars around them were preparing for war.

The morning of the conference had come with the smell of cigarettes. Mike was already out on the balcony, smoking. Mike, thin, tall, Jewish, with curls grown long, unkempt, talked and thought fast in a way Kierk appreciated. In college they played chess with each other while running subjects in neuroimaging studies, and as the research subjects a room over watched the Necker cubes flip in bistability Mike and Kierk would exchange black and white pieces in rapid movements. At the time, the two college friends were also roommates for the summer, living in an apartment absent all furniture except for yoga mats in each of their rooms for sleeping and piles and piles of books on philosophy and science they passed back and forth, until even Mike’s smoking habit had been transmitted to Kierk.

The welcome seminar to the conference was an affair of Brazilian coffee and glass chandeliers, plush leather chairs and bite-size berry tarts. A few people whose books Kierk had read welcomed the crowd. One of the first seminars was run by a member of Antonio Moretti’s lab, which Kierk would be joining in the fall, so for three hours Kierk took copious notes. Next was an array of seminars held in large presentation rooms, which Kierk bounced back and forth between.

There were pathology talks:

“—a blindsight patient acts blind, they use a cane, their family members say that they’re blind, they live the life of a blind person. A lesion to their primary visual cortex severs the main visual input stream to the brain. Yet if you toss a tennis ball at them, they’ll catch it—”

Neuroimaging talks:

“—as you can see, we’re showing this whole-brain ignition, which is very rapid and occurs after the stimulus is presented. So basically, instead of something being processed in a specific region, it’s more about how the signal becomes integrated with the ongoing process that already dominates the brain, but this process is itself a mystery—”

And philosophy talks:

“—while no one has yet solved the scientific mystery of consciousness, it’s worth noting that theories are currently substrate neutral. There’s nothing special about neurons, no magic fairy dust that makes them consciousness. Because of this, we don’t know where consciousness ends or begins in nature. What about complex systems? Or computer programs? Artificial intelligences? Or networks of interacting agents? After all, you yourself are merely a mob of neurons, all acting in concert, and somehow those neurons collectively generate experience—”

In the late evening everyone left the hotel, their black dress shoes and heels shining wet across concrete, oblivious to the watchfulness of the citizens they passed. After a few hours the same polished shoes all stumbled back to the hotel, as did Kierk and Mike after taking shots with some of the grad students, and it was only when they got back and drunkenly switched on the TV that they saw the cop cars on fire and the police in their riot gear marching in lockstep, and protesters called the Black Bloc, who wore ski masks and all-black clothes, and were smashing windshields and throwing Molotov cocktails into empty police cruisers, all of which had happened just blocks from the conference hotel.

The next day Kierk and Mike were standing around their poster, smiling vaguely and hopefully at each passerby. The two of them were wearing their nicest dress shirts and ties, looking out of place for how young they were. Then came the mind-numbing hour of explaining their poster over and over to passersby in thirty-second sound bites.

They ended up outside just after noon, with Mike smoking and Kierk throwing pebbles against the side of the conference building. Far away, sirens wailed, coming and going.

A young man about their age walked past them wearing a backpack. They both noticed it was unzipped and a black mask peeked out. Sharing a look of silent agreement, Mike flicked his cigarette and Kierk threw his last stone and they began to follow him.

As they traveled deeper toward the areas of the previous day’s protests the police activity grew around them. People were walking in odd paths on the sidewalk to avoid the shards of broken glass from shattered payphone booths and bus stops and bottles. Kierk paused in shock when he saw the arm lying on the ground in front of him before realizing it had been dismembered from a shop mannequin. Other parts were lying about: a leg poised on a bench, a head tilted skyward in a tree. Shop owners were out boarding up windows. Unmarked white vans blasted down empty roads and through red lights for no discernible reason, a sea of tinted windows moving and crisscrossing in a higher order that looked random from the ground.

Mike and Kierk were swept away with the crowd, and soon began to see the first gangs of riot police dressed in black body armor with opaque, light-reflecting helmets, their badge numbers covered up with black flaps of fabric. The two ended up following a thin stream of people through lines of standing cops containing and directing the flow. They realized they were surrounded by an army that was shuffling closed, everyone flowing in the suggested direction, walking quickly or jogging down the only available route, and then they were funneled out into the south end of Queen’s Park.

The statue of John Macdonald looked like a focal point for the protesters. There were at most a thousand, congregated densely in the front with a long petering tail farther back into the park. Behind Kierk and Mike, from the direction they had just come from, there were almost as many police as there were protesters. Cop cars were parked sideways in the street and, far in the back, a division of Mounties patted the sweaty flanks of their horses outfitted with blinders and equine armor. The protesters, skewed toward the young, seemed motley and unorganized. Some passed around stainless steel water bottles, signs held down at their sides. A few of the protesters looked out for the hell of it, but others wore UV-resistant sunglasses and were tan and fit, like they had just come out of some protester boot camp.

The day was dipping toward boredom for all involved. A shirtless man sat on the top of the statue, flapping his arms. Signs were laid atop one another on the ground, people sat scattered and cross-legged. A few of the braver citizens had walked directly up to the police and began to chat with them, exchanging jokes. Getting responsive faces, so nervously encased in plastic and armor, to laugh.

A man in his thirties with a beard and with forearms a deep tan shared his water bottle with Kierk, who looked fundamentally out of place in his dress shoes and dress shirt and dress pants and little laminated conference badge. Wiping his mouth, Kierk handed the water bottle back. “Hey, man, I appreciate that. So what are you protesting about?”

The protester looked around, out at the police. “The world’s pretty fucked up. What’s not to protest about?”

“Actually, that’s a pretty good answer…” But the protester was already moving off, because he had noticed something Kierk hadn’t, which was that there had been some kind of change in the air, in the mannerisms of the cops. The police, arranged in a loose line a couple hundred long, twenty deep in places, seemed to be organizing into different contingents. Somewhere in the city, a single person behind a desk, having in mind the Molotov cocktails used on empty cop cars yesterday, having heard reports of cops being sneered at or bullied and the windows of shops being broken, distilled all these individual facts into the alembic of binary command: Do It. And the order had been relayed down the hierarchy from the original node, spreading out and multiplying diffusely along the branches until it reached an output layer thirty-thousand times larger than the source at locations all throughout the city.

Shots went off—the police were firing into the crowd. Kierk hit the ground, rolling away as the screams began to ring out. Looking up, he couldn’t see anything, but people had stopped running. Kierk was one of the few on the ground. Mike was gone. Standing, he saw a haze of dissipating yellow gas, and realized it had been the sound not of bullets but pellets of tear gas. As the gas cleared people were falling over themselves trying to get out. A girl was too slow and the cops descended on her, binding her wrists as she screamed and her friends made confused half steps forward, yelling at the cops to let her go but keeping their distance as the girl was dragged by her feet back behind the lines. The last thing Kierk saw of her was her head bouncing along the concrete sidewalk as her body slipped from view.

Something in the crowd broke. It grew more vocal, more collectively responsive; it shifted with more unity, it roared with more certainty. An agreement was implicitly reached. A single plastic water bottle was thrown in an arc, splattering onto the clear riot shields and then spinning away fizzing under booted feet.

—“You call yourself citizens!” —“That was someone’s daughter!” —“Take off your masks!” —“Show your badge numbers!”

More water bottles created a rain of objects, most plastic but some metallic, chrome, along with balloons filled with paint. In response the army of police began to do snatch-and-grabs, performed in a regimented, almost ritualistic, manner. First the heavily armored ranks in the front would open up and out would sprint a pack of more lightly armored cops bearing batons. The crowd would react like all prey throughout life’s history has reacted, surging away as those nearest tried to outrun not the cops, but the other fleeing people. The pack of police would home in on the unlucky, the unwary, the slowest, or one of the really hard-core professionals who wanted to be arrested and so stood waiting, making a peace sign, and then the baton would take them behind the knees, or at the shins, and the protester would be swarmed over like an obscuring pride of lions onto a gazelle. A moment later the handcuffed protester would become visible again as they were dragged back behind the police army’s line. Then the crowd of protesters that had surged away in fear would refill the gap, moving right back up against the row of shields.

Maybe on the thirtieth or so snatch-and-grab Kierk and Mike literally bumped into each other as they ran from a raid. They had left objectivity a while back so they ended up right at the front, chanting and screaming in a chorus with all the others.

—“SHAME! SHAME! SHAME!”

The cops’ gas masks made them into armored bugs, things carrying death-wands, multilimbed. They beat their batons against their shields in unison, they stepped in unison, they breathed in unison. They closed ranks like centurions locking their shields together and then would push forward into the screaming, biting, shoving, crying, fighting mass of the crowd. By then Kierk had a serious antifascist psychological response going on and ended up getting too close, and so he didn’t notice that from the back of the army a few dozen armored horses bearing masked riders had all been maneuvered up behind the front line. Mike and Kierk were both right up front when the ranks of the cops opened up to clear space and from merely twenty feet away a cavalry wedge of two dozen horses charged the crowd.

“Oh fucking Mounties!” Kierk managed to get out, before he turned and grabbed Mike by the arm and the two of them were sprinting away, the thunder of hooves behind them. Leaping over a row of hedges, they ended up clear of the charge, but turned in time to see a backpack-wearing man whom they had raced past be trampled by three of the horses. His body and backpack flapped around like a rag doll. The girl next to them kept up a high, continuous scream. Then the cavalry wedge wheeled around and was absorbed by the waiting shield wall. There was a shocked, low silence, but still the protesters regrouped, re-congealed. And over and over the same series of events repeated themselves as the protesters were slowly, one foot at a time, pushed out of Queen’s Park and into the Toronto streets.

The two of them ended up separated from the rest of the protest by a series of police rushes and advances designed to carve up the main mass. They were together with maybe three hundred protesters on a tight little street. It felt boxed in because the only exit was the far terminus of the street, what seemed like a world away, where cars were peacefully passing. The sides were a flat wall of buildings.

At first everyone relaxed. The rest of the cop army kept streaming past. Some of the protesters in the little group tried to keep the energy up but everyone felt splintered, cut off, they couldn’t even see any of the other groups, just the endless passing legion of police. Then the thin strip of cops guarding the entrance of the street suddenly got a whole group of reinforcements, tripling their numbers. As the legion kept streaming past, the armored cops at the mouth of the street began to beat their batons against their shields and advance. Kierk suddenly felt that everyone in the crowd was thinking the exact same thing.

—There’s only one exit to this street in the far back and if any of these passing police circle around and block it off then we’ll be trapped in here and we’ll all be beaten and arrested and so we have to get to that end of the street before they block it off and wall us in because they are probably circling around right now.

The thought raced across the crowd like a neural pulse through a web of synapses, everyone sparking off at once, and in about five seconds suddenly all three hundred people were surging, running, forming a stampede. The line of police followed the running protesters at a jog, banging their shields like they were flushing animals. As the stampede gathered force there were calls for everyone to stop, to slow down, but by then it was too late because people were now running just to keep from being trampled, their eyes wild and rolling.

And over the moving mass of bodies, within it, everywhere and nowhere all at once, hung a single feeling, felt by each person, yes, but also all on its own, a dull beast experiencing fear and existing only for a few minutes.

Kierk saw someone go down in his peripheral vision, and then in front of him a bicycle stand, and with no space on either side of him to move out of the way he had to jump clear over it, landing wildly before being quickly enveloped again. He saw the form of the woman running next to him stumble and he reached out and grabbed her hand, yanking her forward and keeping her on her feet. They ran holding hands and when Kierk glanced over it was a middle-aged blonde woman who looked like a suburban housewife, her hair up in a bun, her mouth a thin line, her eyes grim concentration. Her hand gripped his like a vice and they balanced each other amid the surging motion until everyone burst like a flood out of that thin street and the dull beast that had only known a single feeling in its brief life dissipated.

As Kierk and Mike would learn the next day, at that very instant their names were being called at the conference—“Kierk Suren? Kierk Suren?”—and heads were turning in the well-lit and calm main room, a slow stir among a well-dressed crowd. The pair had won the best student poster prize, but with no one to accept it, the conference organizers had finally, and awkwardly, given it to the runner-up.

Hours after the mad rush of the mob, Kierk was sitting on a small brick wall off of a sidewalk in a little shady spot underneath a tree. Beyond him, small sounds still exploded into motions of people running from the aftermath or the racing forms of ambulances, shattering the glass garden of silence that had grown up toward the sky with the exhaustion of everyone, the exhaustion of the protesters, police, bystanders, the exhaustion of police dogs that lay panting in the shade. Mike was away getting them hot dogs and water from a nearby food stand and Kierk was depleted and waiting, his stomach rumbling among the people milling around, recovering in lower murmurs. A few smaller bands of riot police marched by but without a critical mass of people it was as if a truce had been called, clemency granted, and now the scattered groups were merely citizens again. A play had ended and the actors, still in their makeup, were mingling with the audience.

Kierk, however, was still eyeing the loose formations warily. Across from him, on the other side of the small street, one of the riot police had stopped while the others went on ahead. The officer proceeded to draw a plastic water bottle from his belt and take a few long sips, then poured the remainder over his head and face. Finished, he looked at Kierk, noticing that Kierk, exhausted, was rubbing his elbow absentmindedly and had blood running down the side of his head because he had been whacked by a stray baton, that his eyes were red and bloodshot from the gas, the left eye so much so it was puffy, that he looked like he reeked of pepper spray and his tie was loose and low and twisted around, that in the evening doldrums his clothes hung loose on him, that he had dark pit-stains under the arms of his dress shirt, and there was blood—not his own—splattered on his slacks. The cop, a stocky man of about forty with his hair so wet now with sweat and water it looked like he had been swimming, noticed all this and only solemnly nodded to Kierk. And Kierk, seated on his little brick wall overlooking the passing of pedestrians, thought about what that man’s day must have been like, the soreness of his quads, what it felt like to have wet hair and a right shoulder on fire from swinging a baton, his visual field and his feelings toward the mess of a protester sitting on a low brick wall across the street, sharing this moment with him. Kierk thought of the suburban housewife running beside him, the feeling of her hand in his. Considering these things he was a still point in everything. The water seemed to drip off the stocky cop’s head in slow motion and a car moved past like a slow thrumming beast.

It was only a few minutes until Mike would return with hot dogs and the news that he had decided to become a war correspondent instead of a scientist, but at that moment Kierk, still dazed, brought his hand up to his ear and felt the sticky aching spot that hummed when he touched it. Every sound was somehow both muted and loud as if the streets had become an amphitheater, unique, clear, real, and behind it all there was the double-thump sound of valves opening and liquid pumping through and Kierk could not tell if it was his heartbeat or a portent of the world spirit, but he could feel that the brick under him was a solid surface, his mind was a tuning fork still resonating, the air was a medium for prophecy, the glare of colors were bombing past him like schools of fish exploding in the setting sun—at the exact origin of this he felt he was a djinn at the center of history and knew that he would be the one to solve the mystery of consciousness.

Erik,

This was my favorite scene in your book which I actually read twice. The way that Kierk was able to see the parts of the riot and the whole scene as a living entity had me mesmerized. I loved the book's mystical feel as Kierk's mind drifted into the Tree of Life to look for the answer to consciousness. The dream like scenes that may have been real. Was it a murder or an accident. The mystery of it all was great. I think that this book needs a sequel. Revelations II - The Answers. Please, please continue Kierks search into the unknown. Keep in mind that it is often an authors second or third book that is a great hit. Recently an authors third book got my attention and it was then that I headed into Jabberwocky and asked for everything that author had ever written.

It was on May 17th (Desiderata#25) that I had asked if this scene was an example of causal emergence? I am now thinking it may be more like your Integrated Information Theory. Either way I enjoyed this scene above all others.

The search to definitively delineate consciousness may forever be like dividing the distance between any two points in half ad infinitum…or a dog chasing its tail. New words/ terms will surely be added to the vocabulary but consciousness will forever contain knowledge , not the other way around.