The White House agrees you have a small brain

Human extinction and AI denial

I come bearing bad news. You have a small brain. It’s tiny, really. Although before you take umbrage, note I too have a small brain. In fact, every human who has ever lived has possessed only a meager clump of matter to think with. And this objective smallness of our cortices has been an unremarked upon and unchangeable background fact of history. Humans are stupid. Everyone knows it. Life goes on. Since everyone is stupid, the playing field is even. Yet, there’s no rule of the universe the playing field stays anything close to level, once you start building intelligences other than the human. Life might not go on.

So says almost everyone who matters in AI. Just yesterday morning, The New York Times reported:

A group of industry leaders is planning to warn on Tuesday that the artificial intelligence technology they are building may one day pose an existential threat to humanity and should be considered a societal risk on par with pandemics and nuclear wars.

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks, such as pandemics and nuclear war,” reads a one-sentence statement . . . The open letter has been signed by more than 350 executives, researchers and engineers working in AI.

The signatories included top executives from three of the leading AI companies: Sam Altman, chief executive of OpenAI; Demis Hassabis, chief executive of Google DeepMind; and Dario Amodei, chief executive of Anthropic.

At this point, of the three winners of the Turing Award for deep learning (the scientific breakthrough that’s behind all current AIs), two of the three of them—Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio—are warning that AIs could make humanity extinct. The third, Yann LeCun, is a pro-AI evangelist who now heads AI at Meta, and thinks the situation will turn out fine because he’ll just program AIs to be “submissive.”

The momentum is now clearly on the side of the worriers. Look at how the reaction to AI risk has changed in the last two months alone, as judged by the White House Press Briefing room:

While it may feel like the risk from AI has jumped to being taken seriously very fast, that’s because AI has itself leapt forward so quickly, and everything about the technology so far hints at extinction risks. Consider how, according to insider accounts of the people who red-teamed it early on, GPT-4, the world’s most advanced AI, prior to getting the reinforcement from human feedback on its answers, was an amoral monster. It was willing to do almost anything, even suggesting and helping plot assassination. It was just as smart in its initial amoral murdering phase as it was in its current robotic butler phase. In fact, according to OpenAI, without active effect to counterbalance it, making GPT-4 more aligned with human values actively degraded its performance! Yet, right now, there are no explicit laws in place that require OpenAI to even do the meagerest of alignment at all, and no regulatory agency to oversee it.

Despite stated widespread agreement coming from researchers frightened of the very technologies they are building—like the corporate leaders of most major players in the AI space signing a letter saying “what we’re doing has a risk of human extinction”—there are still holdouts in the form of AI risk deniers who think this whole thing is an overblown millenarian panic. People like Yann LeCun, Andrew Ng, or Tyler Cowen, who recently pulled out the “R-word” when he said:

I think when we’re framing this discourse, I think some of it can maybe be better understood as a particular kind of religious discourse in a secular age, filling in for religious worries that are no longer seen as fully legitimate to talk about.

I personally have not found that actual religious adherence itself plays a role in discussions of AI risk. But, if we’re not using the term “religious” in a strict sense, I agree with Tyler Cowen: at its heart, the AI debate hews close to a religious discourse in that it touches fundamentally on the nature of the human and humans place in nature, and whether that place is comfortably assured or not. I think, however, the more religious inclination (again, a term being used in a loose way) is soundly on the other end. I suspect that, deep down, AI risk deniers hold a position traditionally held by lot of religions: that we’re above biology, above certain cold iron laws about intelligence, brain size, and evolution, and that our position as this planet’s dominant species is magically assured. Unfortunately, this isn’t true, because while

organic brains are limited, digital brains aren’t.

The threat of extinction in the face of AI boils down to the fact that artificial neural networks like GPT-4 are not bounded in the same way as our biological neural networks. In their size, they do not have to be sensitive to metabolic cost, they do not have to be constructed from a list of a few thousand genes, they do not have to be crumpled up and grooved just to fit inside a skull that can in turn fit through their mothers’ birth canals. Instead artificial neural networks can be scaled up, and up, and up, and given more neurons, and fed more and more data to learn from, and there’s no upper-bounds other than how much computing power the network can greedily suckle.

GPT-4 is not a stochastic parrot, nor a blurry jpeg of the web, nor an evil Lovecraftian “shoggoth,” nor some cartoon Waluigi. The simple but best metaphor for GPT-4 is that it’s a dormant digital neocortex trained on human data just sitting there waiting for someone to prompt it. Everything about AI, both what’s happened so far with the technology, as well as where the danger lies, as well as the common blindspots of AI risk deniers, all click into place once you begin to think of GPT-4 as a digital neocortex—the high-level thinking part of the brain.

While GPT-4 does have a radically different architecture from our own biological brains (like being solely feedforward and synchronous, whereas our own organic brains have a lot of feedback and asynchronous processing), AIs are neural networks inspired from biological ones. AIs have a learning rule that changes the strengths of the connections between their neurons, just like us—except their learning rule is applied from the outside by their engineers during a training phase, unlike us, who are forever learning (and forgetting). When artificial neural networks are trained, they often develop the properties we associate with real neural networks like grid-cells, shape-tuning, and visual illusions, which is why researchers in 2019 proposed a “deep learning framework for neuroscience.” There are even some prominent arguments that our own brains follow learning rules not too dissimilar. This similarity is why I advanced the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis, which argues that dreaming is a form of data augmentation, like a noise injection, that makes our nighttime experiences sparse and hallucinatory, and evolved to prevent overfitting.

The source of rapid progress in AI has been “scaling,” which means that artificial neural networks get smarter the larger you make them.

What’s interesting is that biologists have known about their own organic version of the scaling hypothesis for a while. The larger an animal’s brain, particularly in relation to its body size, the more intelligent an animal is. Scaling in AI almost certainly works for the same reason evolution gets to intelligence via increases in brain size. Which means we should ask:

does GPT-4 already have a bigger brain than you?

Probably not quite. GPT-4 likely has about 1 trillion artificial synapses (called “parameters”). How many synapses does the human brain have? A lot more than that—sometimes the number is ball-parked at around 100 trillion. None of these numbers are exact (we don’t know GPT-4’s real architecture, OpenAI won’t tell us, and we don’t know the real number of synapses in the human brain, neuroscience isn’t advanced enough to give more than rough estimates). And what matters is not just brain size, but brain size relative to body size. That’s why blue whales, with their enormous brains, are not smarter than humans, since so much grey matter is devoted to their behemoth bodies.

But, outside of primary sensory, motor, and somatosensory areas, it is very possible that the number of synapses devoted to general abstract intelligence in a human is quite smaller than the total number of synapses. Let’s say 50 trillion. Maybe even just 20 trillion. You see where this is going? We’re getting awfully close. If we get another order-of-magnitude jump, then GPT-5 might even reach these sort of numbers, if OpenAI gets ambitious enough.

While others have created more in-depth guesstimations of organic brains vs. artificial neural networks in terms of parameter counts, it’s not clear that any of these guesstimates are actually better than the simple comparison I just did. It’s also complicated by the fact that the architectures are so different, e.g., in AIs a layer of neurons can be all-to-all connected (that is, any neuron can connect to any other), which is impossible in the human brain. And that might matter a lot, as analysis of brain anatomy has shown that humans have more cerebral white matter (long-distance connections) than the other great apes, so all-to-all connectivity might be a fundamental advantage.

Every time someone has tried to predict some limit off of the mathematical details of deep learning, they’ve failed. Consider the case of Turing Award winner Judea Pearl saying that since AIs are based on curve-fitting they can never understand causal reasoning. Seemed like good a priori reasoning to me at the time! That proposed limit lasted a couple years, but now of course GPT-4 easily can reason about causality.

Far more likely: there just isn’t any limit to how smart things can get, if you give them brains 10 times larger than humans. Then 100 times. Then a 1,000 times. You can just keep making larger and larger digital brains, with more and more layers, and training them on more and more data, and they will get smarter and smarter.

Now, maybe scaling stalls out temporarily. One example might be that there’s not enough data to feed the models. Another might be just that training runs become prohibitively expensive over the next few years. E.g., Anthropic is a company planning to create a possible GPT-4/5 competitor, and they just pegged the training cost of such a competitor at a billion dollars (and Elon Musk just bought tens of million dollars worth of GPUs for training runs to build Twitter’s AI).

But even if there is a stalling out for a while, in the long run all that does is lull people into a false sense of security. Right now there is no evidence, none at all, that scaling brains up and training them on more data up ever stops making them more intelligent.

Which means that the central question of AI is:

Are human brains magic?

This is where I think the religious aspect of the debate comes in: do you believe there is something really fundamentally special about the human brain? For instance, do you believe in a soul? Just be clear: I don’t think it’s stupid to have such beliefs. While personally I don’t know about a soul, I do think that our consciousness, our experience, our qualia, is indeed a real and special quality, one that AIs, at least the current kind, probably lack. Maybe there is even some quantum magic happening down in the bowels of dendrites, or the kind of interactionism that Princess Elisabeth called out as impossible. Who knows?

The bad news is that we have good evidence none of this matters when it comes to intelligence. Even if humans have a soul, or a spark, or some ineffable quality denied to the mere matrices of machines—or even if some particular religion is right!—what we must take away from the recent progress in AI is that our consciousness and specialness is only one way of accomplishing intelligence. Intelligence can do without all that, given enough data, like being trained to predict the entirety of the internet. GPT-4 can write a better academic essay than most of the people endowed with such magic, if it does exist. It can get above average on difficult quantum physics exams or solve complex economics exams containing novel questions not found elsewhere. Go talk to the average person on the street, and ask them the same questions you ask GPT-4, and see what the result is.

I’m not saying that human experts don’t still have an advantage when it comes to cognition compared to GPT-4. They do. If you do something for a living, or even just have a deep interest in a subject, you can still outclass GPT-4 in many ways, and spot its non-obvious mistakes. And it can only run sprints, cognitively, anyways, so even if it beats you for a while it’ll flag as it gets distracted or spiral down a rabbit hole of its own making. But to say that will last forever is human hubris. Especially because

AI gets intelligence first, and the more disturbing properties come later.

When evolution itself built brains, it worked bottom-up. In the simplest version of the story, it first went things like webs of neural nets or simple nuclei for reactions, which transformed into more complex substructures like the brain stem, then the limbic system and finally, wrapped around on top, the neocortex for thinking. All the original piping is still there, which is why humans do things like get goosebumps when scared as we try to fluff up all that fur we no longer have.

In this new paradigm wherein intelligences are designed instead of being born, AIs are being engineered top-down. First the neocortex, and then adding on various other properties and abilities and drives. This is why OpenAI’s business model is selling GPT-4 as a subscription service. The dormant neocortex is not really a thing that does anything, it’s what you can build on top of it, or rather, below it, that matters. And already a myriad of people are building programs, agents, and services, that all rely on it and query it. One brain, many programs, many agents, many services. Next is goals, and drives, and autonomy. Sensory systems, bodies—these will come last.

This reversal confuses a lot of people. They think that because GPT-4 is a dormant neocortex it’s not scary, or threatening. They use different terminologies to state this conflation: it doesn’t have a survival instinct! It doesn’t have agency! It can’t pursue a goal! It can’t watch a video! It’s not embodied! It doesn’t want anything! It doesn’t want to want anything!

But the hard part is intelligence, not those other things. Those things are easy, as shown by the fact that they are satisfied by things like grasshoppers. AI will develop top-down, and people are already building out the basement superstructures, the new systems like AutoGPT, which allows ChatGPT to think in multiple steps, make plans, and carry out those plans as if it were following drives.

It took about a day for random people to trollishly use these techniques to make ChaosGPT, which is an agent that calls GPT with the goal of, well, killing everyone on Earth. The results include it making a bunch of subagents to conduct research on the most destructive weapons, like the Tsar bomb.

And if such goals are not explicitly given, properties like agency, personalities, long-term goals, and so on, might also emerge mysteriously from the huge black box, as other properties have. AIs have all sorts of strange final states, hidden capabilities (thus, prompt engineering), and alien predilections.

Fine! Fine! An AI risk denier might say. None of that scares me. Yes, the models will get smarter than humans, but humanity as a whole is so big, so powerful, so far-reaching, that we have nothing to worry about. Such a response is, again, unearned human hubris. We must ask:

is humanity’s dominance of the planet magic?

AI risk deniers always want “The Scenario.” How? they ask. In exactly what way would AI kill us? Would it invent grey goo nanobots? A 100% lethal flu virus? Name the way! Sometimes they point to climate change models, or nuclear risk scenarios, and want a similarly clear mathematical model of exactly how creating entities more intelligent than us would lead to our demise.

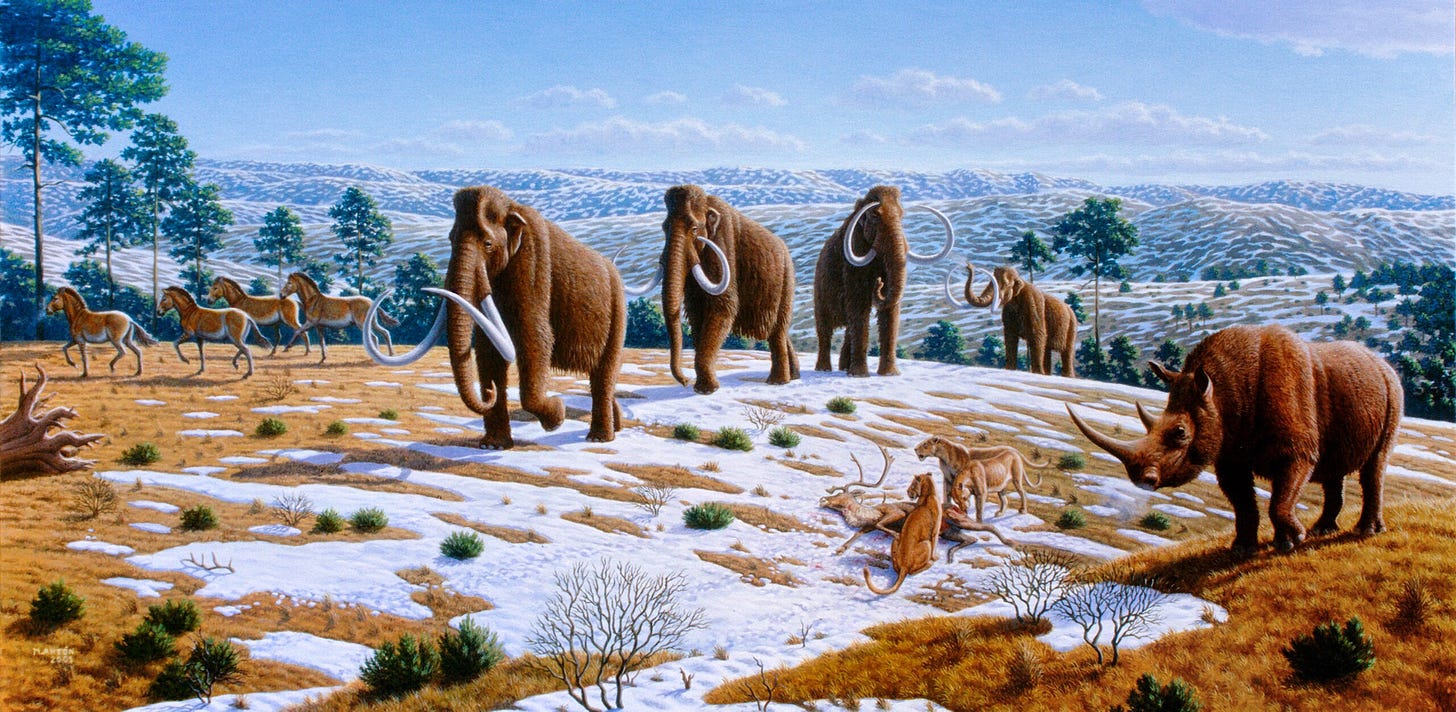

Unfortunately, extinction risk from a more capable species falls closer to a biological category of concern, and, like most things in biology, is just too messy for precise models. After all, there’s not even a clear model for exactly how Homo sapiens emerged as the dominant species on the planet, or why we (likely) killed off our equally intelligent competitors, along with most of the megafauna, from giant armored sloths to dire wolves. It wasn’t a simple process. Here is what Spain looked like in ~30,000 BCE:

Now such megafauna are gone, and the lands are plowed and shaped, because we were so much smarter than all those species. In historical terms, it happened fast—these animals disappeared in what biologists sometimes call a blitzkrieg, timed with human arrivals—but there was no clear model that we can apply retrodictively to their extinction, because dominance between species and extinction is a “soft problem.”

Similarly, the eventual global dominance of AI all but ensured by a no-brakes pursuit of ever-smarter AI is likely a “soft problem.” There is not, and never will be, an exact way to calculate or predict how it is that more intelligent entities will replace us (in fact, intelligence itself is hard to measure—as I’ve written about, IQ tests get more unreliable the higher the numbers, so even just measuring intelligence is a “soft problem”).

In a way, this is again a “religious” (not being strict here) aspect of AI risk denial: taking AI risk seriously is the final dethronement of humans from their special place in the universe. Economics, politics, capitalism—these are all games we get to play because we are the dominant species on our planet, and we are the dominant species because we’re the smartest. Annual GDP growth, the latest widgets—none of these are the real world. They’re all stage props and toys we get to spend time with because we have no competitors. We’ve cleared the stage and now we confuse the stage for the world.

If we are stuck with our limited organic brains our longterm best chance of survival is simply to not build extremely large digital brains. That’s it. In more technical terms: we need to put some sort of cap on the amount of scaling we allow artificial neural networks to undergo, like limiting the size of the training runs, or having hard caps on the capabilities of models so as not to exceed human-level experts. AI past a certain level, and AI outside of that approved by an international regulatory agency that keeps close watch on the products, should be banned. This is our Golden Path.

And for AI risk deniers who might be disappointed or even mad about what looks to be a decisive initial victory in the court of public opinion, at least in getting everyone to take AI risk seriously, I suggest a certain mantra, one every member of humanity should start saying to themselves. It goes: I am a limited creature. I am a limited creature. I am a limited creature.

I am a limited creature.

I have conflicting feelings about this.

On the one hand, I don’t deny the risks that AI suggests. The attitude that LeCun projects on twitter, for example, seems too arrogant, not well thought out, and almost reactionary in the sense of being opposed to new ideas. I think Dawson Eliasen puts it well in his comment.

Also, to be clear, I am not denying that artificial intelligence can be dangerous and the possibility that there’s an existential risk to humanity from it. All the recent developments in AI and LLMs are seriously impressive, ChatGPT is fucking crazy, especially from the vantage point I had a 3-4 years ago, when BERT was a huge deal.

On the other, I am starting to really dislike certain notes in the AI risk alarms, mostly from the voices in the rationalish adjacent circles. I agree with you that some arguments of AI risk denial have religious undertones because of their dogmatism and careless dismissal of others’ concerns. But to me the religious flavour is much more prominent in the AI existential risk discussions because of the magical thinking, panic, and lack of engagement with what AI has already done today.

1. How to stop AI doom from happening? Let’s work on AI development and deployment regulations for humans and human organizations, that is the most important thing. Even with all the wars and conflicts, we have used this approach to mitigate other existential risks (nuclear wars, biological weapons). Without it, even if we “solve” AI alignment as a theoretical problem (and there’s a question if we can), we are still in danger because of rogue agents. If we only had that part of the solution, on the other hand, we’re not in the clear, but we’re much safer.

2. People talk about hypothetical situations of human extinction, but don’t mention the actual, very real problems that AI has already introduced today to our society: ossification and reinforcement of inequality and unjust social order in different ways. Why don’t we try to solve those issues and see what we can learn from that? I am not saying that we should stop also thinking in more long-term and abstract ways, but I am not sure I have seen any AI alignment researcher engage with work by Cathy O’Neil, Joy Buolamwini, and Timnit Gebru, for example.

3. As I said earlier, what the current generation of transformer models can do is crazy. But people also overhype what they can do. If you’re not convinced, skim a recent review on LLM capabilities — https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.11504.pdf — where the authors looked at over 250 studies, at the very least look at the titles of the subsections. For example, the authors find that “[l]anguage models struggle with negation, often performing worse as models scale.”. I am not denying that LLMs are intelligent in many ways, in fact more intelligent than humans in plenty, but if they have trouble with negation in certain contexts, I find it hard to think of them as on a path to more a *general* intelligence, just an intelligence that is more proficient in domains that we are not. For example, while you dismiss embodiment, I think there are good reasons to think that it is still a problem that’s far from being solved.

Or see https://arxiv.org/pdf/2304.15004.pdf that make the following claim fairly convincingly: “[we] present an alternative explanation for emergent abilities: that for a particular task and model family, when analyzing fixed model outputs, emergent abilities appear due the researcher’s choice of metric rather than due to fundamental changes in model behavior with scale. Specifically, nonlinear or discontinuous metrics produce apparent emergent abilities, whereas linear or continuous metrics produce smooth, continuous, predictable changes in model performance.”. Makes you think about AGI risk arguments from the current models differently as well.

And while working with GPT-3.5 recently, I can’t escape the feeling that it is just a super powerful recombinational machine. I am very certain that humans do a lot of that in our mental processes, but not *only* that, and you can’t reach AGI without that last missing part. While I see no reason why AGI or ASI could not be developed in principle, I don’t see how that could be possible without new breakthroughs in technology and not just scaling. So when prominent alignment people like Paul Christiano suggest that just a scaled-up version of GPT-4 could create problems with controllability (https://youtubetranscript.com/?v=GyFkWb903aU&t=2067), it’s not that I think that he’s definitely wrong, but it does make me question the risk alarmists.

To kinda sum up, instead of focusing on specific things that we can do today (regulations, solving the problems that we already have and learning how to address longer-term potential problems from those solutions), I see *only* abstract discussions, paranoia, and magical thinking about unimaginable capabilities of future AIs based on impressive, but not completely incomprehensible results of current models. That seems like magical, religious thinking to me.

As always, thanks for the post, Erik, a pleasure to read!

P.S. Also Meghan O’Gieblyn’s “God, Human, Animal, Machine” makes a lot of great points about similarities between religious and current technological thought, I highly recommend.

"If we are stuck with our limited organic brains our longterm best chance of survival is simply to not build extremely large digital brains. That’s it."

The fact that this very simple concept seems to evade so many of the "Best Minds" is proof to me that they are not, in fact, The Best Minds. I will not worship at the altar of idiots and fools.

Perhaps An AIpocalypse will happen, and in place of Intelligence, Wisdom will finally be crowned king. Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a man's mind.