Billionaires have polarized space exploration

The coming space politics of Ups vs. Downs

If it suddenly seems everyone has an opinion about space exploration, that’s because the inevitable has happened. Now that our “titans of industry” have finally started doing more than manipulating bits on screens and selling ads, it’s obvious to all a new space age has started. This has been quietly building for a decade, kicked off formally by NASA’s 2010 Commercial Crew program that contracts private companies to bring supplies and personnel to space. The program’s structure ensures no real NASA involvement at the hardware or software level, just funding and oversight (consisting mainly of liaisons and post-hoc approvals). One obvious outcome of this change is the decreasing difference between “astronauts” and mere “space passengers.” There was nothing for the astronauts to do on the recent SpaceX crewed launch—the astronauts sat, their training rendered unnecessary, as the Crew Dragon capsule docked itself to the International Space Station. The people on the rocket could have been accountants, for all it mattered, and it’s this that means the number of humans off planet will increase exponentially, since we can finally start sending just about anyone.

Those who’ve been keeping a close eye on space travel know all this. Now others do. The triggering Branson spectacle of a happy billionaire floating weightless, and the promise of an upcoming Bezos spectacle of the same, has activated the beginnings of a public response and a space politics that is going to last through the 21st century.

For what this new age actually brings to mind is an earlier historical era when men of extreme wealth, like Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, connected the continent with railroads and reshaped America to their whims. These men were all billionaires, at least in the terms of their day. Many built local railroads, stringing up the coast with them, just like how in this decade the Moon and Earth’s orbit will become abuzz with activity. But the true accomplishment of this space age will mirror the true accomplishment of the industrial one: the establishment of a transplanetary “railroad” between Earth and Mars, which will resemble in time, newsworthiness, and financial commitment the building of the original transcontinental railroad in the 1860s.

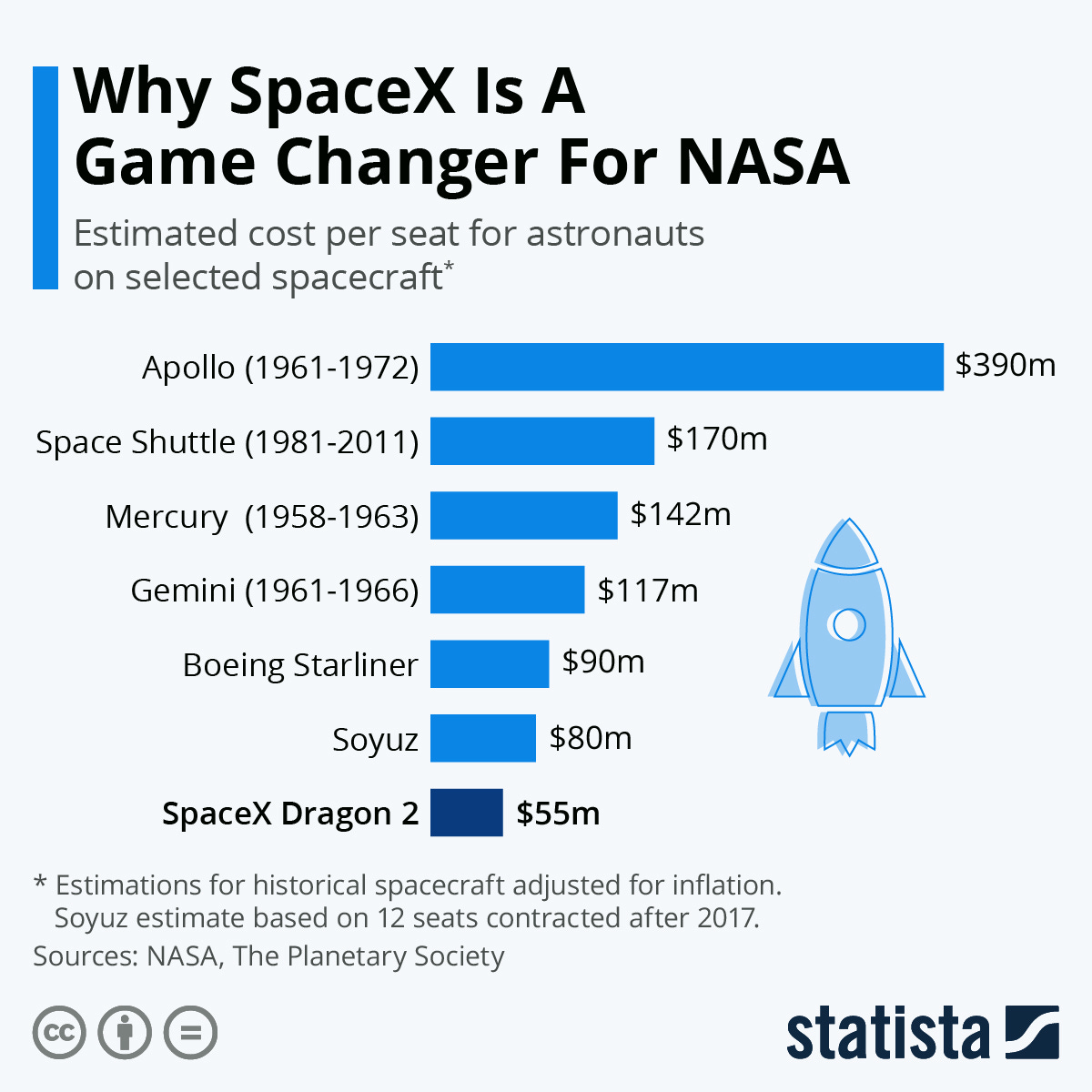

Of course, this new transplanetary route won’t be a road, but will take the form of a fleet that gets assembled and launched every (roughly) 2-year window. The ships that run the transplanetary crossing together will be a menagerie of private companies, but just like the transcontinental railroad, they will have government support. After all, the building of the transcontinental railroad was not hugely dissimilar to the public/private partnerships being pursued by NASA to great success (as measured by cost per seat, SpaceX is going for less than a third of what it used to cost to get the space shuttle to orbit).

There are two camps, or reactions, to the beginnings of this new transplanetary fleet, as well as the more local activity that will occur on the Moon and in low-Earth orbit in the next decade. These two camps will eventually become entrenched political positions over the issue. You’re an “Up” if you think that human civilization should move to other planets. You’re a “Down” if you believe the money that goes toward space exploration and colonization is simply better used here on Earth. This goes especially for privately-funded missions, which Downs view as gross extravaganzas. Being a Down is not an intrinsically luddite position: you can be an advocate for effective altruism, an old-fashioned proponent for charity, or think all the money should be diverted to combat climate change as an immediate existential threat.

The biggest issue for Downs is that they have no control over billionaire’s excess wealth; sure, you can prevent them from private space exploration and colonization via legislation, but you can’t guarantee that this money goes anywhere but to yachts and mansions and the standard billionaire one-upmanship that occurs out of public sight. The Down position is further complicated by the fact that billionaire spending isn’t either-or. Jeff Bezos has put together a 10 billion-dollar “Earth Fund” to fight climate change, which is more than the 7.5 billion he’s put into Blue Origin. Meanwhile SpaceX’s Elon Musk also runs the world’s largest electric car company, and Branson has also pledged billions to fight climate change and advocated for a Clean Energy Dividend that goes further than a carbon tax on corporations. But a Down might argue it’s a matter not just of money, but of disproportionate time and energy spent on space, seemingly evidenced by billionaire excitement about space and minimal interest in climate change.

On the other side, the biggest issue for Ups is not only that space colonization is technologically difficult but also, as we’ve seen this week, that the optics of it can become extremely problematic, especially if expansion becomes a flagrant celebration of wealth (or if there are the kinds of schoolchildren-watching accidents like that of the Challenger disaster).

I’ll put my cards on the table: I’m an Up. And not because I’m enamored of billionaires, but because I think the long future of humanity is galaxy-wide, and quite frankly we need to seize the opportunity to expand while the technological and cultural window is open. It may not always be. This is a notion of destiny that goes beyond mere utilitarian reasoning. I’m an Up because I dream of space. A dream about our destiny but also our past, for as the science fiction author Dan Simmons wrote:

…the cosmos persists—we dream of floating in the womb, of our mother’s heartbeat surrounding us, of the freedom before birth and perhaps after death. Our species waits to swim in this new sea.

Sure, “swimming in a new sea” is a pretty high-minded teleological and perhaps overly-romantic stance, but that’s exactly my point: being an Up isn’t necessarily a thoughtless embrace of rampant capitalism. You can be an Up and want billionaires to pay their taxes. You can be an Up and want billionaires to donate more to fight climate change. You can be an Up and acknowledge that billionaires are not some mythic class made of pure distilled Americana and bootstraps but rather the lucky—scratch that, the extremely lucky. But can you be an Up and want there to be no billionaires? Here’s where it gets unavoidably political and capitalism does enter the picture. Because that’s a harder needle to thread. Thomas Edison did a lot of his experiments with electric lights in J.P. Morgan’s garage, right before the two wired up New York and then later America. Who can say how it could have happened otherwise?

It’d be a lot easier to be an anti-billionaire Up, or more broadly an anti-capitalist Up, if NASA had maintained a progressive pace to space exploration, the clearest and most obvious public good imaginable. If they had just managed to actually keep going into space and innovating with engineering in the one domain that everyone previously agreed there should be government funding of, rather than leaving it to the private sector. But in retrospect (and I say this as a fan) NASA dropped the ball. Massively. Whatever the culture and impetus they had from the golden age of space exploration, it was lost in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s. You can blame whatever you like for this—blame funding, blame the other political side, blame public support waning, blame NASA bureaucrats themselves, whatever, but the space shuttle retired in 2011 and America as a nation was grounded. At the time the retirement of the shuttle seemed to me the culmination of the winding down decline I’d been watching as I grew up in the space desert that was the 90s and early 2000s. Instead of a moon base or an expanding space station, it was a time of expensive, unreplicable, and zany over-designed unmanned missions, like bouncing robots in big balloons down to the martian surface, as if NASA was the Wile E. Coyote backed by a couple billion in government funding. Even now, people are hyped over NASA’s drone helicopter on Mars that flies for only 90 seconds at a time, a thing that is, let’s be honest, basically just a publicity stunt. For real colonization, for real exploration, for real scientific understanding, we need boots on the ground on Mars, and this was always true.

So then the question becomes: are boots on the ground possible without billionaires? I don’t know—who can even answer that? Find me the closest possible world in which we are still getting this new space age and there are no billionaires and I wouldn’t mind hopping streams to there. But we live in this world. And in this world, which is not the best of all possible worlds, the hard truth is that when you admire the NYC skyline you are looking at Carnegie steel.

And now that billionaires have taken over from the failures of the government, it’s inevitable that the universal bipartisan support of hypothetical space travel breakdowns. And not just because of who is funding it, but because it’s no longer hypothetical. For another hard truth is this expanse off of Earth is not going to be pretty. People are going to die. They will die when the lights go out or when a suit punctures or, most likely, they will die instantaneously after rocket failures. Extraterrestrial living conditions will be occasionally closer to the 17th century than some futuristic fantasy of ease. Humans going about their lives in the constrained and precarious conditions of space and on Mars will naturally make squeamish those who are used to having a Whole Foods in driving distance. It will be a return to an earlier form of human existence, truly hardcore pioneer in a way that doesn’t really fit with modern sensibilities.

Despite the hardship, as Elon Musk said, going to Mars will be “the greatest adventure ever.” And humans can take hardship, although this is easy to forget, given how far up most people’s problems are in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Yet the memory of travel in such a cramped hold with nothing but hardtack and prayer is still there, in our bones. I’m likely a Mayflower descendent, as are 35 million other Americans, the ancestors of whom lived for two and a half months stuck in the middle deck of the Mayflower, not allowed as passengers to go up top or below decks, with a mere five feet five inches of ceiling height. Portholes were the only light of 102 people crammed into about 1400 square feet—probably far less roomy than whatever the Starship voyage to Mars ends up being. The descendents of these folk are all over New England, and that’s who I grew up with: Winslows and Brewsters and Hopkins’s. They’ve done it once, they can do it again.

Of the 102 Mayflower pilgrims, the majority didn’t make it past the first winter. Malnutrition and disease were the culprits. But at least some of that should be alleviated by our technology, so hopefully the first settlers to Mars won’t be the Red Planet’s version of Wisconsin Death Trip. I actually doubt the truly bad outcomes—the Martian city will likely be well-funded, with good medical care, but things in general will be cramped, and massively inconvenient, at least by current standards, with nary a Starbucks in sight.

All to say that even if everything goes well, being an Up is not going to be the most palatable position. It remains to be seen whether our current culture has the stomach for any of what’s about to happen. I hope it does. And I hope that, even as these political positions become more entrenched, people remember that everyone just wants what’s best. While there’s still broad bipartisan support for space exploration, it would be immensely unfortunate if the intrinsic polarization of the USA led to Up being a republican position and Down being a democrat one. There are already early indications a split along party lines as the inexorable Schelling point of Red vs. Blue drags this into its gravity well. So I’m afraid that precisely this is going to happen.

Best case scenario: this issue doesn’t fall along the traditional political axis, but at this point there’s no way to prevent Ups vs. Downs becoming a real thing. Should we let billionaires take humanity to the stars? I know where I stand, and you may know where you stand, but over the next few years everyone else is going to have to make up their minds. Shall we start designing flags?

Seriously, we’re going to need some flags.

Hello, Mr. Hoel! I am a high school student, and I would like to answer your rhetorical question, "But can you be an Up and want there to be no billionaires?". I do not believe billionaires should exist because there is no way they can get to that status without exploiting others. Besides, they possess more wealth than the world’s poorest 4.6 billion people. However, space exploration can help find new methods of sustainable agriculture, as well as renewable energy. I think it is possible to be an Up (maybe not in the truest sense you describe) and want no billionaires. Also, I have a question: do you think it is easier to be an anti-billionaire Up in other countries?

Great analysis Erik! I totally agree. In a slightly different context, Hugo de Garis refers to Ups and Downs as Cosmists and Terrans. I’m a Cosmist and I want to go Up. Never mind the billionaires, they have a role to play, and so do we.