Video! Game! Addiction!

A guide for navigating a world of infinite entertainment

There’s a profile I once read of an American drone operator, one who bombed people in Afghanistan from the safety of an air-conditioned building near Las Vegas, a guy who spent a whole virtual war in Nevada looking at an infrared screen, choosing little targets. Eventually, the operator began to dream about it. His dreams combined his drone-view experience of Afghanistan and his favorite game, World of Warcraft, where characters from the games would appear and run along the desert sands in infrared.

In college I played World of Warcraft too—my first semester I spent way too much time on it, and I too would dream of it, occasionally. We were both inside the supersensorium. And by “supersensorium” I mean the entertainment analog to a “supermarket” with all its conveniences and stocked shelves. What makes a supermarket so super is that everything is so readily available, organized, accessible, standardized. So too now with our screens, through which we can easily access almost any available pre-packaged entertainment. The result is that, just as obesity rates took off after supermarkets became the dominant way everyone in America got food, so have rates of entertainment addiction followed the rise of the supersensorium.

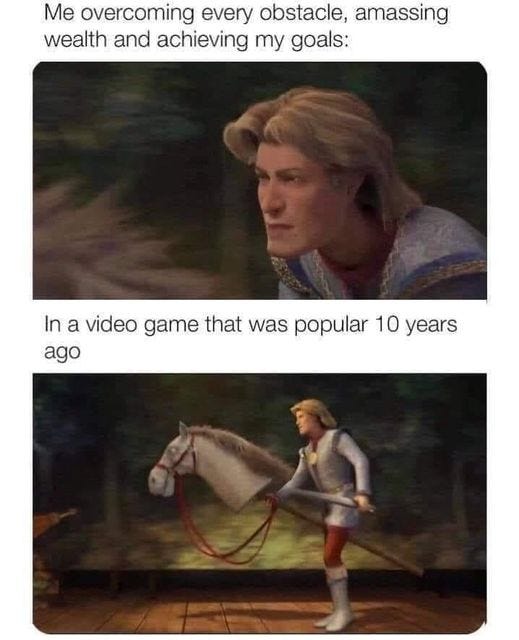

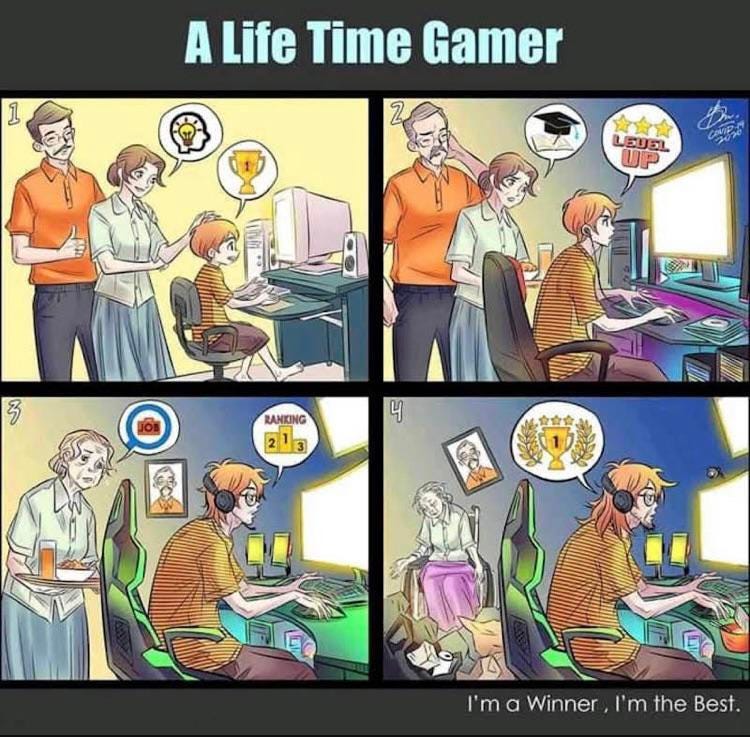

The subreddit r/StopGaming is a repository of stories and memes about what being totally captured by the modern supersensorium is like—mostly from young men. The worst are “I lost my wife” level stories, along with plenty of laments about spending 63,000 hours (~7 years) on games, all while being only 30. Sometimes this is handled with humor:

Other memes are pretty straight to the point:

Alexey Guzey, now the head of the New Science organization dedicated to improving science (and sometimes blogger), bravely published his journal (so keep in mind what follows is written by his high-school self) detailing his struggles with video game addiction back then, and how bad it got:

I was severely depressed for the last two years of high school and for the first year of university and saw a psychiatrist for several months, at some point convincing him to prescribe me antidepressant. . .

I look back at these months and I see nothing good I’ve done. Just memories of me playing games and, literally, nothing else.

Sometime in February, it became clear how boring it is to sit at home all day, constantly trying to find new, interesting videogames. So, I decided to kill myself. I started to research this topic and figured that the best way to properly perform suicide is to [redacted]. Awesome plan, isn’t it?

Unfortunately, it had one big hole in it: my intense fear of death. . .

Point being that some very smart (and successful) people undergo the same issues. Indeed, a lot of very successful people still play video games, and most manage it totally fine, just like plenty of people have a glass of wine with dinner and don’t become raging alcoholics. Sometimes though, things begin to bleed over.

When the FTX cryptocurrency exchange crash was occurring, and Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) was losing money faster than anyone in human history has ever lost money, there was a Twitter rumor that he was doing something very strange: that he had logged on to play a game of League of Legends.

The tweet, if you looked close, was obviously doctored, but a lot of people took it seriously because it seemed so believable. After all, it was known that SBF played a lot of League (which he, of course, had his own justifications for).

In a now-infamous scene, SBF was playing League while on a billion-dollar fundraising call.

Suddenly, the chat window on Sequoia’s side of the Zoom lights up with partners freaking out.

“I LOVE THIS FOUNDER,” typed one partner.

“I am a 10 out of 10,” pinged another.

“YES!!!” exclaimed a third. . .

“I sit ten feet from him, and I walked over, thinking, Oh, shit, that was really good,” remembers Arora. “And it turns out that that fucker was playing League of Legends through the entire meeting” . . .

The B round raised a billion dollars. Soon afterward came the “meme round”: $420.69 million from 69 investors.

(Sidenote: the state of our financial institutions seems deeply stupid.) But to almost anyone who is not familiar with how deeply the lure of video games affects people, this is extremely strange behavior. In fact, it must seem sociopathic—to be gaming during a meeting wherein billions are at stake. May I suggest that rather it was that video games are, for many of my generation (of which SBF is one) a self-soothing activity, and this behavior was more like a toddler fondling a binkie.

And yes, of course all different types, demographics, and creeds beyond young men play video games. Some you might not expect.

And while women can absolutely become addicted to video games, according to statistics of how different demographics spend their time, the scale of the problem, and how women approach gaming both personally and at a cultural-level, is often different. When my male friends have become unemployed, the first thing they do is start gaming harder, and more seriously, and it eats up more and more of their day, which creates an obvious but often very-difficult-to-break cycle. It’s not that they inevitably are consumed by it, and they are doomed—moreso that it threatens consumption, and makes things harder, and that work must be done to prevent it. For the challenge of living in this age is that we must do the boring and unexciting thing of learning how to deal with the superstimuli around us. Survive is pretty much assured. There are no tigers to devour us. There are no predators left at all. But your own appetites will eat you if you let them.

At this point, I think there is a danger of misinterpreting me as saying that video games, computer games, whatever you want to call them, are bad. That their content is stupid, or wasteful, and that young people should spend no time on them at all—an impossible ask, and often, a socially-crippling one. All this could not be further from the truth. I, along with pretty much every guy I know from my generation, like video games. I’ve even written about why I think Esports have advantages over real sports, like deeper player-audience relationships. I think many games are worthwhile to spend time on, and offer experiences equivalently unique to anything that can be found in TV shows or books or films. That is, they can be art. Some of my actual real favorite memories are in games, from the expansive opening of walking out of the initial cave in Skyrim and seeing the dragon sweep past to jocular exchanges with the companions in Mass Effect.

Games are artistically powerful because they are the replacement of one reality with another. They are a substitution, not of what you are viewing (like a TV show) but the very reality in which you as an agent are existing. You become instantiated inside the game, embodied as a virtual avatar. And it is this embodiment that makes something act like another “reality.” Harry Potter books give you access to the the goings on of a fictional world, but you are not an agent in that world, you are not embodied there. But you are embodied in, say, the upcoming Harry Potter role-playing game:

This is the attribute that makes video games unique as a medium, and gives them their artistic flair—you are in the one in the Sorting Hat. This doesn’t mean games are better than other mediums, just that they have their own unique advantages (and disadvantages). As philosopher C. Thi Nguyen argues in his book Games: Agency as Art:

Painting lets us record sights, music lets us record sounds, stories let us record narratives, and games let us record agencies. . . Just as novels let us experience lives we have not lived, games let us experience forms of agency we might not have discovered on our own. But those shaped experiences of agency can be valuable in themselves, as art.

With all that said (and I think it’s important to say), it’s also possible to move beyond valuing games as an artistic medium but as something more like a replacement for lived life. Some even think there is, at an intellectual level, essentially no difference between reality and games—reality is just the biggest and most expansive game. David Chalmers, one of the most prominent contemporary philosophers, has an interesting book called Reality + in which he argues exactly this:

■ Virtual worlds are not illusions or fictions, or at least they need not be. What happens in VR really happens.

■ Life in virtual worlds can be as good, in principle, as life outside virtual worlds. You can lead a fully meaningful life in a virtual world.

. . . We need to make decisions right now about how we use video games, smartphones, and the internet. An increasing number of such practical questions will confront us in decades to come. As we spend more and more time in virtual worlds, we’ll have to grapple with the issue of whether life there is fully meaningful. . .

In many ways, whether intended or not, Reality+ can be read as a high-level defense of gaming, which is referred to almost universally with a positive valence throughout the text (the word “addiction” is only used once, and in a different context). Chalmers certainly thinks life in a virtual world is meaningful, and, as he says, “Most virtual worlds found in video games can be regarded as simulations.” One can draw the inference. Chalmers has this belief because to him reality is nothing more than just the most-detailed simulation, the one that contains all the other ones—the largest Russian doll. And because he perceives no distinction between the dolls, he thinks all the dolls are real. Specifically, Chalmers argued that, since we can refer to things in simulations, and these digital things can have causal relations (e.g., digital money in a game might be used to purchase digital items, occurrences in a virtual world might be counterfactually dependent on other occurrences etc), along with a few other criteria, like whether or not the simulation is “mind-independent” (does it exist when no one is looking, etc), for these reasons therefore virtual realities are the same as real realities.

I agree with Chalmers that we should be clear about these philosophical questions for practical purposes, but my conclusion is the exact opposite. Why? The view of simulations as being equivalent to real reality is, I think, ontologically confused, and relies on an impoverished notion of “real”—as if reality were merely a checklist of properties that must be satisfied, and then we can be sure. It misses the pith of the difference. When you design a Turing machine (such as one that contains a simulation), you can sketch out all of its working on paper, but the thing does not run. Nothing happens. It just sits there. A schematic. An idea. It needs to be instantiated in actual reality in order for it to run. You could, of course, run that Turing machine on another computer, a model inside a model. But then the question becomes: Is that other computer itself instantiated? Or is it merely a collection of formal relations hanging uselessly in abstraction? And so on. Reality itself, the base layer, is always required, and is always the one doing the heavy lifting of actually existing. And it is this heavy lifting which is absent from any schema of purely formal relations like a simulation, and there is therefore a sharp distinction between virtual realities and real ones. As Stephen Hawking wrote in A Brief History of Time, when discussing the same issue but in the context of the laws of physics:

Even if there is only one possible unified theory [of physics], it is just a set of rules and equations. What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe? The usual approach of science of constructing a mathematical model cannot answer the questions of why there should be a universe for the model to describe. Why does the universe go to all the bother of existing?

The question of the missing fire in the equations means that whatever reality is, whatever Being is, it must necessarily be very different ontologically from a simulation, because simulations don’t run themselves, and reality runs itself. And reality runs itself automatically, by fiat, inexorably. For this reason, no matter how detailed one makes a simulation, no matter how convincing the illusion becomes, it ultimately is merely some superstructure on top of actual reality. In a virtual world with virtual physics, the laws of physics in that world possess only borrowed fire. All to say: the difference between simulations and reality is that only one of those goes through the bother of existing, while the other only lazily describes what could exist.

And this is the ultimate, the most abstract reason why the tendency toward video game addiction is so sad, evokes so much pathos—you become addicted to video games because you want to replace your reality with a different one, but the different one is ersatz, and somewhere deep the pointlessness of it all is felt, pixel by pixel. So what to do?

Get older

Some advice, huh? But if video game addiction is the swapping of real reality for an ersatz reality, it makes sense that the best way to stop video game addiction is to improve your actual reality. Mostly, this happens over time—with effort, yes, but time is also important. Life in your 30s is very much not like life in your 20s—perhaps harder, in many ways (a family, etc), and more filled with daily responsibilities, but at the same time it is much more rewarding. Most people actually report being less happy in their 30s, but they are more likely to find life very meaningful, mostly thanks to family and careers.

In fact, at this point I go months to years without playing a game, and I don’t miss it much. Although, every so often, very rarely, a new game comes out, and I spend a bit too much time on it for a week or so before growing mostly bored with it. So it’s a problem that, like many problems in life, eventually solves itself ~80% of the time if you wait long enough.

Become a game snob

As I wrote in “Exit the supersensorium:”

In a world of infinite experience, it is the aesthete who is safest, not the ascetic.

This was my chosen path in my 20s. I am simply a huge game snob. Oh, have you not heard of Pentiment, the new RPG from Obsidian where you try to solve a murder mystery in a medieval abbey?

It’s a great way to learn about medieval Bavaria, and a terrible way to spend more than 20 hours. This approach is like how a film snob might loathe reality TV, and therefore cannot become addicted to watching reality TV. Forget if any of this snobbery is deserved or not, the point is that this approach works. It’s simply impossible to produce 63,000 hours of gaming that I wouldn’t hate—it’s probably impossible to produce even 63 hours, so judgmental, so hair-triggered in my distaste am I.

Avoid installing games on your laptop / work computer

Alexey, for instance, says that the context switch of college was part of the reason why he was able to become much more productive:

One specific instance of university having a large positive impact on my productivity was the discovery that productivity depends largely on the context. I discovered that going home meant I will be playing video games all day long, while staying at the university and going to the library magically allowed me to be productive and decreased the craving for video games by many times.

Of course, some people might simply not game at all if not on their laptop, but perhaps the best solution to this (if you want to pursue moderation) is an Xbox right in the center room of your house that everyone can use. That way, if you’re gaming, people can see you, and if you do too much, you will feel ashamed. It’s a lot easier to develop bad habits out of view.

Play finite games

You might notice a theme here: World of Warcraft, League of Legends, etc. These are “infinite” games wherein you can conceivably sink entire days into. Meanwhile other games are finite—you play through them and you win. There is an end. This is an incredibly important distinction, and what makes MMOs, strategy games (like Starcraft), and first-person shooters (like Apex Legends), so dangerous. They are all infinite games. The content is either repeated mini-games (strategy or shooters), or just a massive amount of grinding for loot and drops in MMOs. Meanwhile, for finite games, they are selling you a packaged experience, like a film or novel, that is one day designed to end, rather than being ouroboros-like, beginning and ending forever.

Oftentimes the most banal statements, the truisms of the world, are the things indeed the most true. They just need to be reframed to feel fresh. It’s easy to say “If you get addicted to video games the best way out is to fill your life with more meaning” because everyone kind of already knows this. It even shows up in gamer speaker, where people are regularly told to “go outside.” “Get some sun.” “Touch grass.” It’s much harder to say it in a way that makes it feel fresh. Like that one should get off the screen and go breathe fire into the equations.

You and I are lucky in that we don't get addicted to games easily. A few times a year I'll binge hard, but after a couple of days I'm back to normal life, usually feeling refreshed. I know that lots of people don't find it so easy to stop.

In college I made the biggest decision of my life: pursue novel writing OR pursue game development. (Most people's biggest decision is 'Who to marry?' but I'm single and will likely remain that way). I chose writing because I've been challenged, edified, and changed by books more than games. But writing and reading are both low on the Supersensorium scale, so I have to carefully limit how much time I spend on other forms of entertainment - especially gaming - in order to preserve the quiet headspace I need. That's a sacrifice I'm willing to make.

Reading slips under the radar. It's not as flashy as TV, movies, or games, but it leaves me satisfied and sedate in a way nothing else does. I'm hoping more people join the de-dopamine push and start to value the slow, healthy forms of entertainment like books. Partly because I know how much it has helped me. Partly so I can sell more copies. It's a win-win.

I hadn't thought of snobbery as a defence against the constant availability of low quality addictive stuff — games, TV, and other media, but also food, alcohol, drugs — but put that way it makes perfect sense. I, uh, might be 5% more of a snob after reading your essay.