Why does culture get less happy year after year?

Our emotional decline into everything being "dark and gritty"

Lately I’ve been working through some old criterion collection movies with my family, and the first thing you notice with old movies or TV is how happy everyone is. Like how abnormally, freakishly, stupidly, weirdly, cheerful. The past is always fundamentally unknowable to us, although the mechanisms by which this opaqueness occurs is unclear, and I oscillate between thinking that people in, say, the 1950s, were fundamentally different from us psychologically and the opposite position that they were exactly like us.

Think of 30 Rock, a TV show about comedy writers writing a comedy TV show. It is very funny, but not one of the characters could be described as happy. The setup (comedy writers working at a sketch comedy TV show) is identical to that of 1961’s The Dick Van Dyke Show (also about comedy writers working at a sketch comedy TV show). In The Dick Van Dyke Show all the characters (including Mary Tyler Moore, the singing/dancing talented housewife) are portrayed as being extremely happy. We readily acknowledge now that The Dick Van Dyke Show is a fantasy, but it’s odd to think that this is a fantasy true in pretty much any old TV show, and often holds in movies as well. Old music also feels more cheerful to me—the ‘50s may have been abnormally Stepford-wives cheerful, but the power rock of the ‘80s is also incredibly cheerful, and consumed today only with a thick dollop of irony on top.

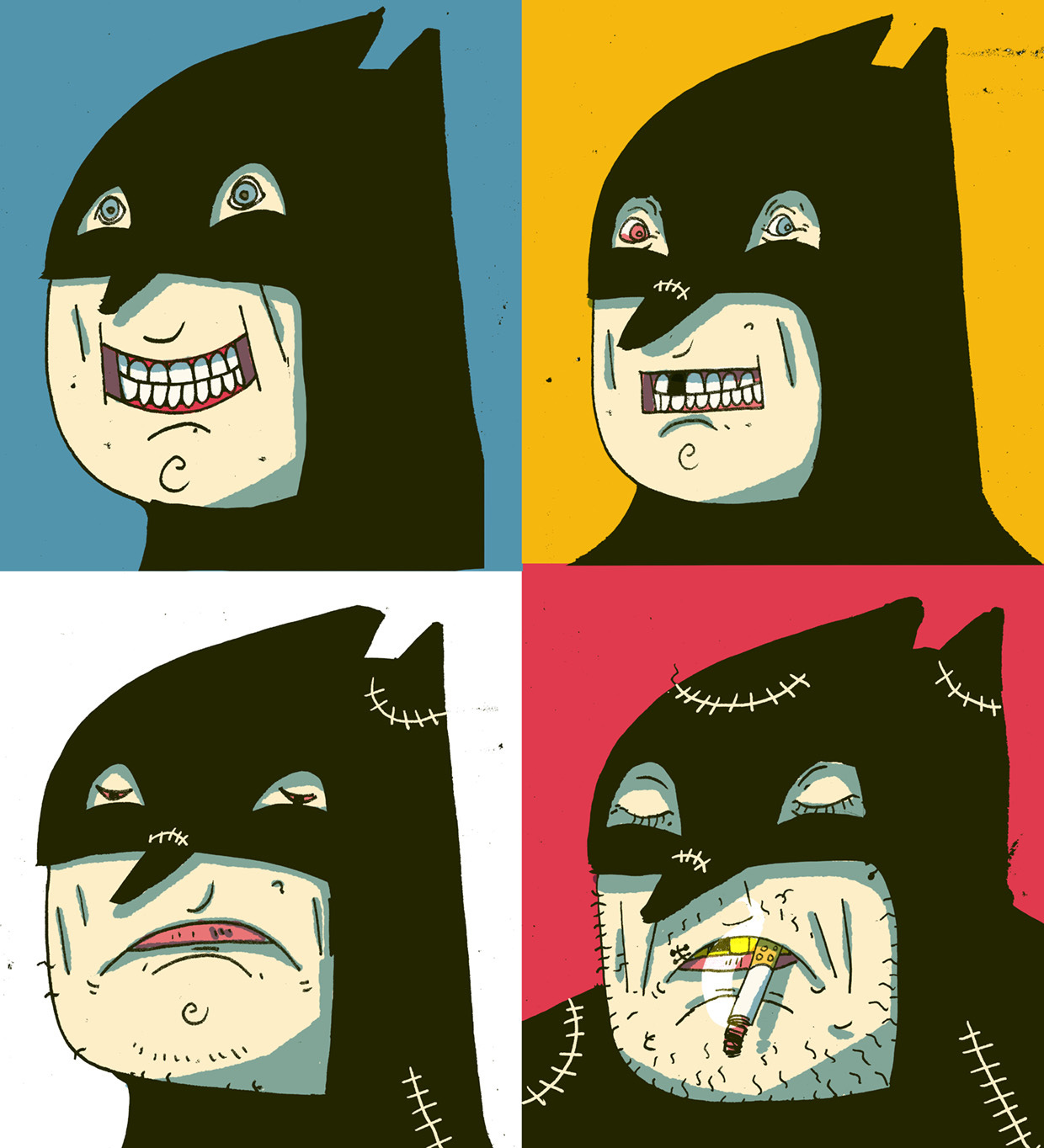

It’s all a jarring contrast to the dominant themes of today’s cultural production, which is “dark and gritty.” The one note today’s entertainment strikes is the depressive tone—and that’s spoken by someone who, at various times in his life, has struggled with depression. But even in the worst bouts of it the experience of my inner life was not as limited in emotional range as many of the shows you can find on Netflix. Or, e.g., Batman remakes.

The tendency for culture to become more unhappy can be seen most clearly in long-running franchises, like Star Trek, since they control for more variables—i.e., it’s the same lore and world presented in separate time periods. Star Trek: The Original Series in the ‘60s started out incredibly hopeful as a TV show and has now decayed into being. . . dark and gritty, just like everything else. The new Star Trek: Picard is, guess what, super dark and gritty. Characters are deeply unhappy and all of them suffer from some form of trauma, and reasonably so, for it has turned out that, in the latest show, the United Federation of Planets was basically a whitewashed neoliberal propaganda government all along, and characters in the Star Trek universe face the exact same political challenges people today face (often the analogies are quite direct: apparently in a recent episode Picard and others go back in time to the current day and stop an ICE bus in order to free everyone on-board). And yet, consider how much darker Gene Roddenberry’s actual life was than the current showrunners of Star Trek (this is from my previous breakdown “We can't imagine an ‘end of history’ in sci-fi anymore”):

. . . he was a pilot in WWII, and later one of his planes went down in the Syrian desert due to engine failure. He suffered two broken ribs but still dragged injured passengers out of the burning plane—the last one he dragged out died in his arms. He took command of the survivors, keeping them alive in the Syrian desert. When a band of bedouin arrived, Roddenberry talked them into only robbing the dead. And it was Roddenberry who made the final trek across the desert alone to inform the authorities of where they were to be rescued. The writer of the more recent Star Treks attended Wesleyan.

Yet Roddenberry offers forth a hopeful vision, while the show’s current writers offer, as usual, dark and gritty. And the same is true, of course, of Batman, another franchise with the same lore and settings but portrayed so differently in our era vs. even, say, the 1960s.

So the question I’ve been dwelling on is: Does this decline in happiness on-screen reflect actual changes to the average happiness “set-point” (if there even is such a thing), or is it just an illusion based on what the different eras happen to portray in their popular fictions?

Certainly there is some evidence that we are, on a personal level, becoming more unhappy.

Although teenagers show a more complicated pattern (why was 2007 such a good year for teenagers?).

But, my take-away from such graphs is that, if you look at the x-axis in percentage terms rather than absolute terms, the decline is not huge. Apparently:

The latest World Happiness Report, released this week, finds that a separate measure of overall life satisfaction fell by 6% in the United States between 2007 and 2018.

And there are all sorts of reasons to be skeptical of data like this—every study is slightly different, the same methods aren’t universally used across time, much of it relies on self-report, and so on.

If we look instead at cultural artifacts at different times, what stands out most to me is that literature is the only medium where the decline of happiness isn’t obviously true. Sure, contemporary literature is almost always written in something that might be called “the depressive mode” (which is probably why so many adult readers have moved to Young Adult fiction: to inject some emotional range in their reading habits), but this trend goes back a long time. The Sheltering Sky by Paul Bowles is incredibly depressing, and it was written in 1949. Rabbit, Run by Updike came out in 1960, followed just a year after by Revolutionary Road by Yates, followed again just a year after in 1962 by Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? All are basically occupying the same emotional range (dark to unhappy) as contemporary television. No one in Joyce’s Ulysses seems particularly happy, and that was published in 1922. And classically, works like Middlemarch and Anna Karenina are taken as emblems of psychological realism, usually because they emphasize the depressive, even the suicidal.

So one hypothesis is that the literary sensibility has been the “true” depiction of inner human life for the last few centuries at least, and that people, even centuries ago, had a similar emotional range. Meanwhile, the newer television and movies were, when they came along, much more public-facing and under mass-scrutiny and censorship and all sorts of lowest-common-denominator effects. Therefore for a long time they dissembled, portraying the world and their current culture as Pleasantville, an effect that has faded with time with the overturning of norms, the decline of censorship, and, most importantly, as I’ve written about before, the replacement of the most prestigious cultural product from actual literature to TV shows.

I’ll be honest—I’m not entirely convinced by this story about literature’s “realistic” depressiveness revealing that humans have changed little psychological. It’s possible that the “dark and gritty realism” take on human psychology and reality itself simply got introduced much earlier in literature and took over, much as it has in film. And it’s not clear to me that, past a certain point, literature really is dark and gloomy. Dickens’ characters often seem to be relatively cheery, despite the fact that their life situations are far worse than the present day. Jane Austen’s characters are comedic even when they are hysterical or nervous. And Roman literature, from operatic writers like Virgil to realists like Catullus, doesn’t really have the contemporary dark and gritty vibe—it is often serious, but not unhappy.

Are the characters in Shakespeare happy? Hamlet, an obvious example of depression, sure, but in many of the other plays there are extremely happy characters. Even in his tragedies, I wouldn’t described Shakespeare’s oeuvre as “dark and gritty,” I would described it as “vibrant and diverse.” If there’s anything Shakespeare is not, it’s one-note.

So which is it? Was it simply that everyone who writes stories and characters was lying in the past, but isn’t now? Has art slowly gotten “closer to the truth” of what human psychology is like, and human psychology turns out to be dark and gritty? Or are humans so plastic that we do adapt, at the level of daily experience, to the culture around us, taking on its forms and moods like we’re cephalopods changing our colors. I’d be open to a yes or a no to any of these.

Regardless, occasionally it might be worth remembering that what we think of as realism, which is basically a synonym now for “dark and gritty,” might fail to capture the actual range of human emotion, of lived inner-life, just as much as the false face of unnatural happiness that was a 1950s television show.

i think there is an (erroneous) assumption in art that unhappiness = interesting, authentic; happiness = boring, phony. this has become a kind of feedback loop in entertainment and life. individuals no longer feel their lives are unique or worthwhile unless they suffer in some visible way, and artists no longer feel their work is worthwhile to an audience unless it offers a reflection of that inner turmoil or external oppression. which is ironic, because so much of the 'darkness' is dull, fake emo brooding that has become predictable. there is little room left for modeling or celebrating joy, the way earlier art often did.

i also think there is a disconnect between lived hardship and what is translated into 'darkness' on the page or screen. the roddenberry example is a perfect case. there was a man who suffered a great deal of hardship, yet rather than casting a dark gloom over his entire existence and work, perhaps it gave his life purpose and meaning... in other words, something like happiness. in the past, a heroic deed would have been understood in these terms. we assume hardship necessitates sadness when often people report just the opposite--they crave the purpose, challenge, or camaraderie of it. those who live sheltered, comfortable lives and write dark fictional stories are possibly the least equipped to understand genuine hardship like roddenberry's. yet, their 'understanding' continues to influence ours through their books and films.

Darkness became associated with depth and authenticity and happiness with shallowness, the false surface. That seems to follow the logic of Psychoanalysis.