Yes, scientific progress depends on like a thousand people

Defending the elite culture of science from both the political left and the political right

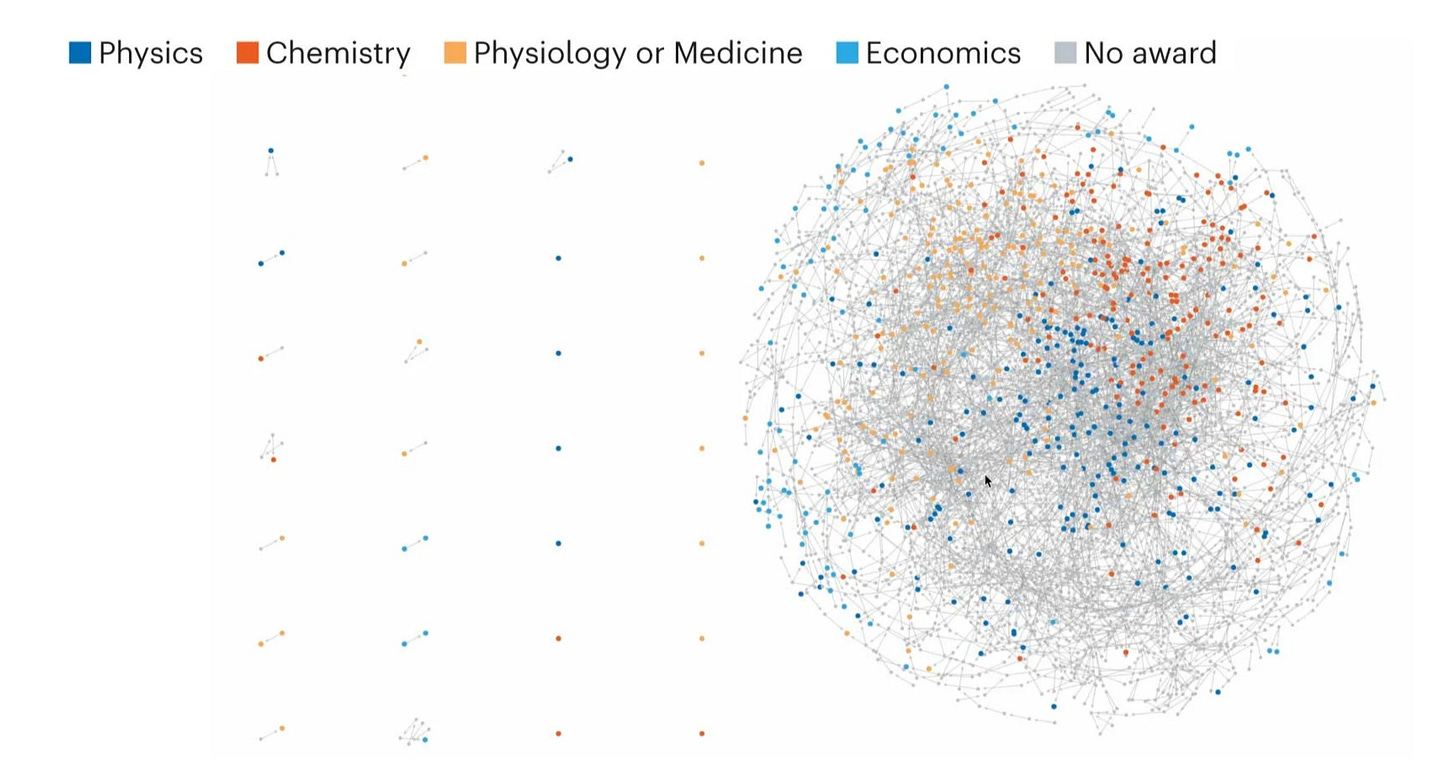

A recent analysis in Nature caused a stir by pointing out that the vast majority of Nobel Prize winners belong to the same academic family. Of 736 researchers who have won the Big Recognition, 702 group together into one huge connected academic lineage (with lineage broadly defined as when one scientist “mentors” another, usually in the form of being their PhD advisor).

Here's the great interconnected ball of scientific social relationships, responsible for large swaths of tip-of-the-spear progress over the past century. Most billionaires, most technology, most startups—arguably almost everything, in fact—is decades downstream of what this ball gets up to.

Regarding its interconnected nature, Nature puts it as:

Prizewinners often beget or emerge from the labs of other laureates. They frequently share mentors or mentees — those who supervised them or their students, or their students’ students.

Who is the progenitor of this tree that became science? When I was asked the same question on X months ago, I replied:

My earlier guess turned out to be correct. According to Richard Tol, the author of the 2024 “The Nobel Family” analysis that the Nature article is based on:

The resulting tree has 33 generations, with Erasmus (1466-1536) as Urahn.

(Urahn means “ultimate ancestor”). I think this is because, as I mentioned in The World Behind the World, Erasmus started what was called the Republic of Letters—essentially just aristocratic nerds writing their discoveries and thoughts to one another—and the Republic of Letters transformed into science as we know it. It's why scientific papers are still sometimes called “letters.” It all used to be mail.

Some people really don't like the result. This was obvious on X, where there was a lot of criticism of the Nature piece. In fact, I’ve found there's a surprising amount of skepticism to the idea that great scientists create other great scientists—something that seems obviously true to me.

I think the sources of this skepticism ultimately falls mostly into two camps.

(a) The first camp believes that this clustering arises solely from elitism and nepotism.

(b) The second camp recoils at how these results conflict with a preferred explanation of purely innate genetic talent—essentially the belief that great scientists are simply super high IQ people, and science’s structure of mentorship, teaching, and apprenticeship is epiphenomenal.

I think both of these camps are wrong and that it makes perfect sense that science would have an elite high-productivity cultural substructure at its apex. And I also think that, while there can always be improvements in fairness to entry, the mere existence of a high-productivity subculture within science is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, maybe the real takeaway here is that we should do everything within our power to protect these people and not interfere with them.