AI makes animists of us all

A kami for every household object

“Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested.” —The Trial, Franz Kafka.

One morning my credit card stopped working. I’ve had problems with it in the past—it constantly spit out “charge denied” at the cashier and I, embarrassed, would be forced to dig out my debit card as the line waited. Such problems never had a cause, for it was always paid down, I have pretty good credit, etc. It would just happen sporadically. Charge denied. But now my credit card has ceased to function altogether, to deny all charges, although not before its last revenge: tricking me into a big double-spend, where it pretended not to purchase something, secretly did, and then I purchased the same thing with my debit card.

The card comes from JP Morgan Chase, a multi-national banking conglomerate (originally founded by Aaron Burr to compete with Hamilton’s new national bank). Over the years I’ve cursed Burr’s name many times during my calls to the company. I always end up with some outsourced help agent, and we have a conversation that goes like this:

ME: Calling for the umpteenth time about this card thinking a charge is fraud. Can you fix this?

CHASE: We can authorize the purchase.

ME: No, I want to change the sensitivity of how the card detects fraud. I can’t call and wait on the phone for an hour to talk to a customer service representative every time I want to purchase something. It does this for like, all purchases.

CHASE: I literally don’t know what you want.

ME: [Explains using the many past examples].

CHASE: What you’re asking for is impossible. I don’t have access to that.

ME: Who does?

CHASE: No one.

ME: What about CEO Jamie Dimon? You’re telling me he doesn’t have access?

CHASE. No. One.

Burr! So here’s what I suspect is happening: it’s not an algorithm that tries to detect fraud on my card. It’s an AI. I suspect the bank, at some point within the long time I’ve had the card, originally started with a fraud detection scheme that was an accessible and explainable algorithm1, that is, a way of deciding fraud at least listable as some definable set of If-Then statements, like:

If card is used in another country within one day of being used in a previous country, then deny the charge.

If card is used to purchase more than $500 dollars online on a non-popular website it’s never been used on before, then deny the charge.

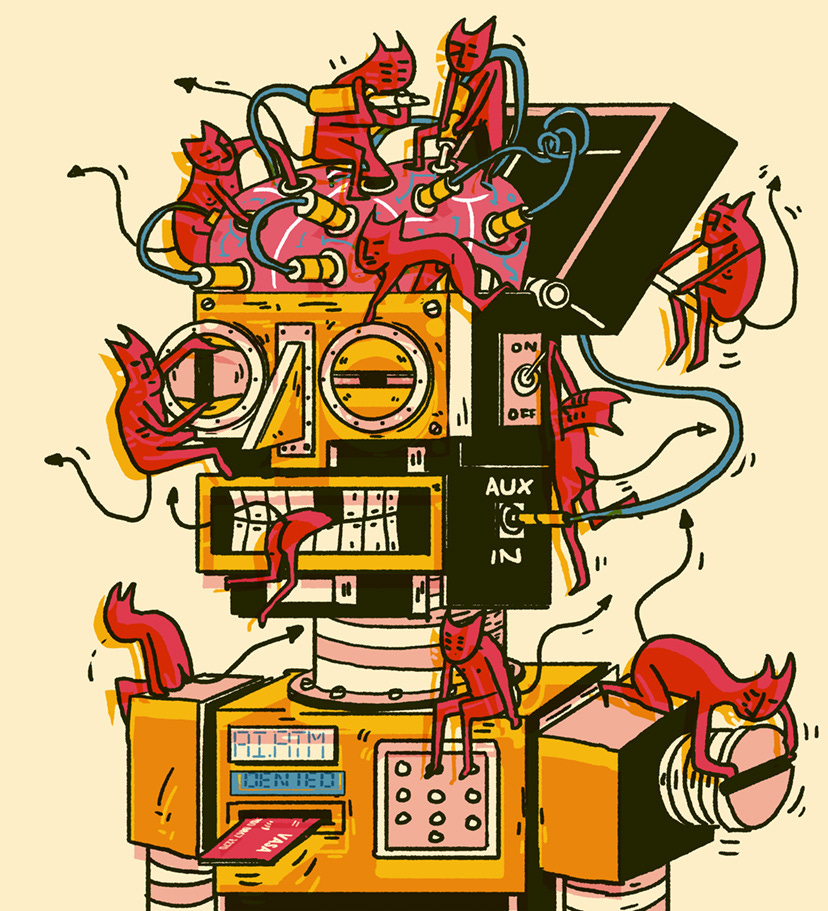

While the actual algorithm was probably much more complex than that, there at least seemed to be levers that a human could reach in and intervene on, like debuggable or changeable code. The card, after all, used to work. Now, my card is governed by an artificial neural network, a black box, that is making these decisions. Head cheese.2 In other words, my credit card has a mind of its own.

Last summer, a journalist from The Guardian reached out to me. They were writing about some research I’d done on the evolved function of dreams. “No comment” was implicitly my reply, because, well, their email had gone to spam. Why? Some oversensitive, overfitted AI jumped on it.

This may seem a triviality, but spam filters can greatly affect the overall success of us who write online. Substack emails just like this one are sometimes sent to promotions, or spam, or what-have-you, in a manner always fundamentally personalized and inconsistent and unknowable. From the LA Times:

Kyle Merber, who writes a weekly Substack newsletter about track and field called the Lap Count, has struggled with similar problems. “People sign up for a newsletter … and they turn around one week later expecting to see it, and they don’t see it. So that obviously affects the open rate, and therefore your growth.”

Merber’s wife is among his subscribers, and . . . Gmail continues to deposit each issue in her Promotions folder. She has tried every solution the internet hive-mind recommends: dragging-and-dropping new issues from Promotions over to the primary inbox; replying to the newsletter as if it were a real person; consistently opening and reading each issue.

“And yet still, for whatever reason, it continues to not populate in her inbox,” Merber said. “I know if this is happening to her, making all that effort, that it’s happening to a lot of people who haven’t maybe done that.”

We can imagine poor Merber’s wife here, desperately moving emails to certain folders, trying to communicate with the mind of the spam filter. Phrases like “It’s obviously mad about something!” are not much of an anthropomorphic stretch here. She is offering, essentially, a kind of ritual—please, nameless entity that controls who can communicate with me, please, let this one through. And it may. Or it may not.

While artificial neural networks work incredibly well (on the tasks they can be trained on), generally we don’t know how or why they work. They aren’t programmed in the traditional sense—their “programming” is in their initialization and training. They learn, very much like brains. If you ask the question “Why did the self-driving car stop at the this stop sign?” you might, in some cases, be able to answer that directly, but most of the time the why is impossibly lost amid the millions, sometimes even trillions, of connections. All you can do is hope they stop.

The chance we ever overcome this issue is, from my understanding of it, essentially nill, and looks further and further away as the networks employed get bigger and bigger. Not that this hasn’t been noticed by AI ethicists, who are particularly worried that AIs will make their decisions based on demographic information, like race and gender, or even names. Didn’t get a new mortgage? Maybe your name is Monique, and the AI was trained on some data set wherein “Moniques” were more likely to default. This problem can be ameliorated by being very careful about the network’s training data, but it can never be fully solved, mostly because all data is biased in some way.

Yet the inexplicability of AI goes far beyond racial or gender bias—almost all an artificial neural network’s decisions are inexplicable, in the way a mute animal’s are. I’ve spent many hours training my german shepherd Minerva, and due to our close relationship 99.9% of the time I know what she’s thinking. Yet occasionally she does something I can’t understand the why of, like leading me over to an empty corner and then gazing up at me. At these moments her eyes contain a kind of inarticulate blankness I’ll never penetrate.

And the problem of black-box AI seems unavoidable. For many types of tasks and decisions they perform better than humans, even though they are inarticulate minds. Who would have guessed that leaving the industrial age and entering the information age would bring about this sort of change? During the industrial age, only other humans had minds, never machines. Perhaps that’s the reason intellectual thought of the industrial age led up to the logical positivism of the early 1900s, which peaked in the denial of meaning to all statements that can’t be tested, as well as behaviorism, which peaked in the denial of all minds. Everything seemed on track for mechanization, for explainability, for the gears of the world to reveal themselves to the average citizen as sane and logical and verifiable.

We find ourselves in a much more anthropomorphic world now. In a sense, it is a return to a pre-industrial age.3 If you ever travel to Japan, you’ll find Shinto shrines sprinkled throughout the cities. There, you can often toss a coin into water, or arrange some rocks, scrape sand, or feed koi fish.

The old Japanese Shinto religion was based on kamis, spirits that inhabited locations, shrines, households, environments. Your actions at the shrines are to appease these spirits, for they are neither wholly good nor evil, but rather reactive, quick to pleasure or displeasure. They cannot be communicated with directly, only through ritual, offerings, and sacrifice.

My credit card now has a kami. Such new technological kamis are, just like the ancient ones, fickle; sometimes blessing us, sometimes hindering us, and all we as unwilling animists can do is a modern ritual to the inarticulate fey creatures that control our inboxes and our mortgages and our insurance rates.

Perhaps it is inevitable that all humans in all times find a way to surround themselves with capricious spirits.

I’m aware that “algorithm” and “AI” are often conflated in their usage. Some might take issue with my distinction. In the broadest technical sense, an AI is indeed an algorithm, but in lay and even academic usage there is often a distinction between the two, with algorithms being things that are, at least conceivably, both directly programmable and therefore understandable by humans.

Neural networks are called “head cheese” in the sci-fi author Peter Watts’s Starfish trilogy, the plot of which turns around the black-box nature of neural networks.

The science journalist George Musser pointed out to me had previously written in Nautilus about how AI has made the world panpsychist, comparing AIs to “forest spirits.” Although I don’t think these new kamis need to be conscious or even proto-conscious, as Musser indicates, to act like minds—rather, the fundamental problem is their black-boxed nature, which is what makes them seem so capricious.

I really like this, it reminds me of the short film Sunshine Bob, which beautifully portrays human helplessness in the face of an increasingly unlistening world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=645OxM9MePA

Great post––the connection between black box AI and kamis is an interesting insight.

Have you read "The Restless Clock" by Jessica Riskin? In it, she argues that pre-Reformation, people in medieval Europe tended to imbue mechanical automata with a kind of vital spirit as well. I haven't verified the extent to which this is true but I thought it was an interesting connection nonetheless.

It also reminded me of something I've been thinking about with respect to "explainability" and AI. I work with neural language models a fair amount for my own research (like BERT or GPT-3), and these are in some sense prototypical black boxes. Even though in theory, we (or at least someone, somewhere) know the precise matrix of weights specifying the transformations of input across each layer, this feels somehow unsatisfactory as an explanation––perhaps because it doesn't really allow us to make generalizations about *informational properties* of the input? And so there's an odd sense in which practitioners have gone full circle, and we are now using the same battery of psycholinguistic tests––designed to probe the original black box of the human mind––to probe these models. See, for example:

Futrell, R., Wilcox, E., Morita, T., Qian, P., Ballesteros, M., & Levy, R. (2019). Neural language models as psycholinguistic subjects: Representations of syntactic state. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.03260. (https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.03260)