Ars memorativa

FICTION: A mystery about the lost art of memory

When Mr. Greene descended into akinetic mutism at the hospital it was widely admitted that the New York Public Library had lost its most knowledgeable collector. As the months passed and he ceased speaking, eating, or even swallowing, it was rumored that a woman, a brain tumor, metal toxins, even the loss of a hidden child, had conspired from within to disable the architecture of his mind. No employee at the library was close enough to him to answer definitively, and no doctor could explain the onset of his vegetative state.

Without a funeral to concentrate it, sentiment was expressed in patchworks through the high halls of the library in diminishing returns. There would be an unfortunate lack of obscure hermetic and occult authors now, with their main purveyor gone. A somewhat bawdy charm would be missed. For who would now ply the widows who visited with quotes from John Donne? On the back office’s refrigerator still hung a Donne quote, which Mr. Greene had written in clean cursive:

She Is All States,

And All Princes I,

Nothing Else Is.

The whole affair was an immense surprise to Edward Montau, the head librarian of the Manhattan branch. And strangely no family members stopped by to collect the assorted trifles Mr. Greene had left behind: an apricot scarf, a pair of fine leather gloves, an umbrella, a dog-eared copy of Yates’ The Art of Memory, a coffee mug, and many torn notebook papers filled with drawings of complicated geometric wheels and numbers. Edward kept the items in a cardboard box underneath his desk. At night, in the tall spaces of the silent library, Edward would spread the items out in different configurations, attempting to complete a puzzle. Yet the archaic drawings, the scarf, the book, the gloves, the umbrella, the coffee mug, all remained vatic, answering a question that Edward could not pose. It was not until Edward took down the scrap of paper from the refrigerator and added it to the small collection that the mystery seemed wholly present. For what could drive a librarian to a minimally conscious state, if not somehow poetry?

Edward still sporadically headed to the Presbyterian Hospital after work and visited the organic statue of Mr. Greene. He never ran into any other visitors, and generally stayed for an hour or so, reading aloud something he knew Mr. Greene, in his arcane epeolatry, would have approved of: the Novum Organum of Francis Bacon, Cicero’s De Oratore, and even some of Leibniz’s original letters that Edward snuck out of the library in his briefcase, titillated at the thought of carrying them on the subway. Occasionally Mr. Greene would drool onto his hospital gown, and when it happened Edward would commit the intimate act of wiping down Mr. Greene’s mouth with a small towel. Sometimes he wanted to shout Mr. Greene’s name as loudly as possible in the stagnant airs of the room. Once he was forced to scream into his hat in a bathroom stall at the hospital, just to get it out.

It was widely known that, prior to his comatose state, Mr. Greene made a habit of staying late at the library, a privilege extended to most employees but used by few. Following the onset of Mr. Greene’s condition, Edward began to keep the same schedule. In the high dark halls he would move through the dim pools of light, browsing the hermetic texts that Mr. Greene had favored. Sometimes, while reading Raymon Llull or Giordano Bruno, Edward would come across a drawing, something mystic and geometric, and he would return to the sketchings of Mr. Greene and remark, occasionally out loud, on the similarities of the images.

Muttering in the dim library Edward watched himself and grew uneasy. His wife, Martha, began to cultivate the cold air of suspicion due to his late stays. Edward could tell by the way she slept just a bit farther away on the bed, the way her legs stopped straying over to his side. He knew she was distancing herself, preparing for a revelation of some kind. In a way he felt sad his aims were so esoteric in nature. It pleased him she thought he could still manage an affair, although it had been a decade since he had done so.

Their fifteen-year old daughter Laura sensed all this, retreating into her own world of high school, of her friends, of piano lessons and texting. Both the women in his life were building arks. He wondered exactly what Laura did when she got home from school, with both parents gone. His suspicions were confirmed one day when he found a used condom in the trash. It had been buried but the family terrier upset the trash can and spread the contents across the kitchen. When Edward saw that condom he had felt only a slight curiosity and in a way, a sense of relief. Laura would never know, they did not talk in that easy way of some families. But he was immeasurably glad that she had her own life, what he imagined and hoped was a passionate life, even if not prudent. He did not tell Martha about the condom. Instead he had picked it up with a paper towel, put it in a new trash bag, and immediately took the bag out to the curb.

Edward’s obsession and odd hours would have been impossible to explain to his family because he himself could not account for his actions. He and Mr. Greene had not been close friends, just congenial and respectful coworkers. They had gone out to the pub a few times together, always with a group of fellow workers from the library. Mr. Greene would sip scotch until he began reciting humorous vignettes of Samuel Johnson from memory. The only explanation to Edward’s building obsession was the need to offer a kind of apologia for Mr. Greene. And he irrationally suspected that would require a mastery of the whole span of knowledge Mr. Greene so clearly possessed.

The obsession was compounded by the belief he had made progress on the mystery. Several things had come together one night when a coworker reminded Edward of a trick Mr. Greene performed several years ago, after someone had noticed him reciting the Dewey Decimal number of a text from memory. Soon Mr. Greene had gathered a small crowd of coworkers who wrote dozens of digits on the blackboard in one of the back rooms, which Mr. Greene would read, then leave the room, and everyone would gather to watch him recall the numbers an hour later. Each time, spaced throughout the day, Mr. Greene had returned and rattled off the numbers in quick succession, his eyes squinting.

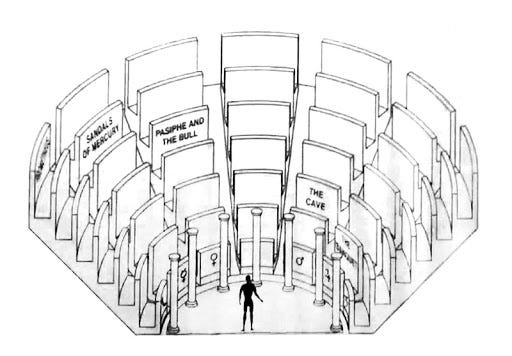

There were also the times Edward had witnessed Mr. Greene speak from memory the full, winding passages of Donne, Keats, or Dante. Mr. Greene would have that same look on his face, his eyes darting about as if examining something. And so Edward became convinced that Mr. Greene had practiced the ancient art of memory. He must have been traversing his own memory palace at those times, finding the beautiful or bizarre images associated with the architectures of rooms or statues, and translating the images with some system into precise phrases, perfectly enunciated.

Cicero dictated that memory palaces were to be made from real well-lit, large and architecturally-pleasing places, and that the images within, representing some fact or figure, be memorable through humor or beauty or sexuality. Edward could now understand why Mr. Greene would stand, distracted, at the entrance to the library staring at the stone lions, Patience and Fortitude. What rich symbolism the Public Library must have offered Mr. Greene, the rare privileged of living inside a building both physically and mentally. Edward even suspected that the library was first a memory palace to Mr. Greene and only later, swayed by the pleasing symmetry of it, a place of employment.

During his research Edward realized how extensive such memory palaces could be. Matteo Ricci, who published translations of Western works during his missionary work in 16th-century China, developed a remarkable memory palace. Several of the books Matteo translated into Chinese were ones he did not take with him physically, but instead had stored in perfect facsimile in the grandness of his palaces, issuing translations years after he physically read them. Edward’s growing suspicion as he plumbed reading lists, notes, and book requests, was that Mr. Greene’s memory palace had rivaled even Ricci’s in grandeur and complexity. For Mr. Greene had been, it was widely assumed, intelligent enough to be a scholar of some renown, but instead had chosen to become the collector for the library. And now Edward understood; there was no place for a man like Mr. Greene in modern academia. Indeed, there was no place for him in the modern world, a place where memory had been given over to machines instead of palaces.

So when Edward took Laura to the Metropolitan Museum to do research for a school project she spent the time texting her friends and he spent it wondering if here, right here, had been present in the mind of Mr. Greene.

When they were eating lunch at the museum coffee shop Laura ordered a black coffee and Edward had been taken back, completely surprised. He shouldn’t have been, she was having sex after all, why shouldn’t she drink her coffee black? So he asked her about her schoolwork and watched her hold her coffee in small hands and blow into her cup small breaths. He got her talking about an art class, and listening to the subtle enthusiasm that went right to her hands, he thought to himself that she was going to be fine, just fine, look at her go.

It was later that night while reading Mr. Greene’s copy of Yates’ The Art of Memory that Edward stumbled across a phrase that struck him in his chest. Underlined three times, written with intensity, it read merely: characteristica universalis. In a midnight delirium he cried out from his office. For both Roger Bacon and Leibniz had sought to create a characteristica universalis, also called a scientia perfecta. An art of memory with combinatory rules and translation systems so perfect, images so revealing of the core reality of what they signified, based in memory palaces so grand, that would allow for a perfect understanding of nature.

As Agrippa said, a scientia perfecta would be concerned with the possibility of describing all knowable things. In the years when Kurt Gödel was starving to death from paranoia of being poisoned he became obsessed with the characteristica universalis, believing that Leibniz had succeeded in his quixotic quest to build a perfect language out of memory palaces, but that it had been erased from history by malevolent powers. It was an area filled with genius and obsession.

Surprised at his own conviction, Edward concluded that such a perfect language, such an art, had been the final goal of Mr. Greene. With renewed passion he returned to inspection of Mr. Greene’s drawings. There was something familiar about one of the huge sketched images, a heavily folded drawing that had the topographical lines and detail of a map. Symbols sprawled up and down it, linked by long knots of connections, lines which gave the drawing a distantly familiar structure.

After weeks of late-night researching, Edward was forced to conclude the drawing was impenetrable. Eventually he simply stopped looking at it, because the cognitive dissonance it produced became unbearable. The drawing was a stopping point for him. Having read everything there was to read on the characteristica universalis, he could do no more than rearrange Mr. Greene’s objects on his desk and pore over the huge mysterious sketch under the yellow lamp light.

At his last trip to the hospital Edward had taken with him a pin. With a feeling of great trepidation, Edward stuck it discretely and quickly into Mr. Greene’s arm. Mr. Greene had flinched in the instinctive manner of an automaton, twitched his arm, but that was all. Edward cried silently and discretely as he wiped down Mr. Greene’s arm and left.

In the distance of the next few days it became obvious there was no mystery. A silly fantasy had been constructed from a few meager occurrences, and Edward had gotten swept up by it. Only he, he thought, would have such an intellectual midlife crisis. He stopped staying late into the night and began to get home early to cook dinner for Martha and Laura. At first his wife seemed even more suspicious about this sudden turn of events, but over the weeks her entire body posture changed into acceptance and relief.

After one passionate night he lay awake listening to the whispers of her breath. In the dark she could shed the years and familiarities which had desensitized him to her. Hadn’t he once seen her flash a tour group at Cornell from his room, and couldn’t he still remember the shouts and laughter from below? Yes, there had been a breeze and it had been spring. In his still comparatively crude memory palace he affixes the image in a place of prominence—the bare arch of her young back in the sunlight leaning out his dorm room window.

That morning he promised Martha that they would start going out again. A date night. Each Friday they would dress up and ride the subway to some restaurant, a review of which he had circled in The New York Times. It was while trying to find such a restaurant, tracing his finger across one of the big subway maps to locate an obscure location on the Upper East Side, that the realization began.

He spent the evening at the restaurant in shock, unbelieving. After dinner he told his wife he had to go to the office, unfinished business, something unclear, and was out the door. Grabbing a copy of the subway map from one of the underground help booths he rushed over to the library, where he laid the subway map over Mr. Greene’s sketches. They fit perfectly.

At this he sobbed, a wrenching hiccup, then fell back into his seat, unsure, doubting. Could a single man make a memory palace of all New York City? He imagined Mr. Greene standing on each street corner, assigning to it a certain seal or sign, a semiotic signifier in a vast system. Mr. Greene would be wearing that apricot scarf of his and his eyes would be squinting.

Yes, Edward could see Mr. Greene at every point of the city, at every place or process which could be considered and compressed as a symbol. At each subway stop or building, at the bistros and the regular saxophone players, Edward suspected that Mr. Greene had subsumed them into the vast web of the memory palace and its system, a memory palace that had grown to the size of the city itself, had taken on its working and shape and scale. The ultimate attempt to construct a characteristica universalis using the city itself as an engine.

Could such a detailed mental city and its memory system begun to move of its own accord? Mr. Greene would have taken care to maintain the connection between the signifier and the signified. Perhaps by arcane laws of the memory system the images would interact, change. To create a characteristica universalis the city itself would have become a tool for thought, and conversely the thoughts of Mr. Greene would have resembled more and more a city.

Edward traveled to the hospital late at night amid this brooding enlightenment. At the front desk the night nurse knew him and let him in despite it being far past visiting hours. Edward sat down in the chair beside the unchanged Mr. Greene and watched the city lights from the pane of the window. Beside him, Mr. Greene took in slow breaths, and the scholarly mind of Edward could not help but summon the quote:

Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire. The world, unfortunately, is real; I, unfortunately, am Borges.

Edward had no proof. All was conjecture. But he was also calmly, perfectly certain. In an effort to supersede language Mr. Greene must have recognized that he would have to represent reality directly and totally. To become it. But what he had not realized is that a city thinks slowly, in great circles of history. Time for a city of signs, a city of memory, would be slower than for a man. Perhaps Mr. Greene was at first startled to see the hands of a clock revolve faster than expected, or how other people seemed to speed across the room. As he sunk deeper into the events of the city inside of him passerby would have become as hummingbirds. Did it happen all at once, or slowly? The final piece of the puzzle, the note left by Mr. Greene, took on a startling metamorphosis:

She Is All States,

And All Princes I,

Nothing Else Is.

Edward saw the future. He knew that on that bed Mr. Greene would rot and die like a spent dandelion. And it would go unsuspected to all but Edward that with him would die an entire city of inhabitants still running in correlation with the real. A city caught in a snow globe of a mind. A world for idealists, for in that living memory palace Berkeley was correct and all is idea in the mind of God.

Perhaps there was even a sign for Edward himself in that great expanse of memories which moved all by themselves. Perhaps there would be a time, many years hence, when the respirator stopped working, and the signs of the city would look to the sky, the sign of Edward among them, pausing in their daily routines, the ideas of their lives, and they might wonder—why does the sky break?

A theme that I love from Revelations and this piece (and one that speaks to your background as a scientist) - the vertiginous self-doubt of pursuing a mystery and questioning whether or not there even is a mystery in the first place (and in the process questioning whether you have begun to lose your grasp on reality).

Bravo, Borges would like this one I think. Ok now it's time for me to write that Borges-inspired short story I've been putting off...

Are you familiar with Ramon Llull? I got a copy of DIALOGOS: Ramon Llull's Method of Thought and Artistic Practice. Incredible resource to supplement Yates. You also might like the work of Michel Beaujour on rhetoric.