Five intellectual figures who left us too soon

Unfilled shoes in our culture

Perhaps it is the string of losses among intellectual figures that has me dwelling on the past. Recently Noam Chomsky was falsely reported dead (he is still recovering from a stoke, although at 95 it looks grim and there is no evidence he will be able to ever talk or write again). A month before that, the great philosopher of mind Daniel Dennett, who I was at Tufts University with, also passed (neuroscientist Anil Seth wrote a touching obituary in Nautilus).

But there are even more intellectual figures lost too soon who lately come, mirage-like, to my mind in this dry dead summer heat. In some ways, toying with the idea of these figures living longer has made me worry that the post-2012 world would have destroyed them anyways. Perhaps their reputations would have suffered greatly, living long enough to become the villain (at least, according to social media). Regardless, here are some figures who I’ve been thinking about, and who died before our culture shifted, and who I do wish had lived to today.

There are shoes standing empty on the cultural stage. Here are five pairs of them.

Carl Sagan

Died 1996, age 62. Myelodysplastic syndrome (an incredibly rare bone marrow cancer). Carl evinced a deep earnestness that would make him an easy target in today’s world of social media dunks. By all accounts loved by his children (if not, given his string of divorces, his wives) he had only rare public scandals, like the speculation around his penchant for smoking weed (the rumors were true; in fact, he argued for marijuana in a published essay, one written anonymously as a “Mr. X”).

To this day, his Cosmos TV series (now hard to find online) remains the untouched pinnacle of TV science communication. I remember watching Cosmos box sets when I was 12 and I’m not entirely sure that I would have wanted to become a scientist without them. Sagan’s earnestness mixed with his casual charm and his grand vision. In a way, he was doing “longtermism” before any of those terms became popular, for what made Sagan’s vision attractive was that he clearly placed the story of humanity in relation to the cosmos, to the universe, advocating for space exploration and technological and humanistic advancement.

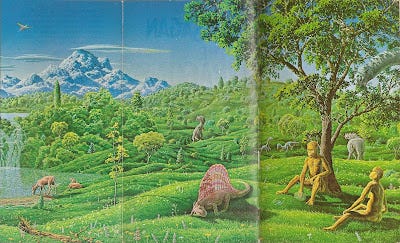

But Sagan—an agnostic, not an atheist—also offered more than just bright white science and overly-literal rationalism. I remember so vividly the fold-out book cover to his The Dragons of Eden.

Such artifacts pulled at me, whispered in strange tongues, for science from Sagan sometimes seemed primeval messages from an older, greener, more mystical world.

Much sneered at by the elites in the scientific community at the time due to his public outreach—such as being denied academic tenure at Harvard as well as denied entry to the National Academy of Sciences—Sagan was the first person to perfect science communication; arguably, in a way unsurpassed to this day.

Right now, bits of Sagan remain, scattered across the cosmos. There is a message from him waiting to be picked up on Mars. He and his last wife, Ann Druyan, were involved in compiling and launching the famous Golden Record on the Voyager Spacecraft, a record containing information about Earth for any far-future alien civilizations to find. Our songs. The sound of a human kiss. A baby’s cry. The thundering of a storm at night under a curtain of rain. And they also decided to include a recording of human brain waves. It was Ann who went to get them recorded from herself at Bellvue hospital in New York City. This was days after their engagement, so what she thought about the whole was how it felt to be a human freshly in love, and how much she loved this man, Carl Sagan. Now those brainwaves are traveling at 35,000 miles an hour, leaving our solar system for the great interstellar void of stars beyond, awaiting some unimaginably distant discovery.