What the heck happened in 2012?

On the year the modern world was invented

Decades. We’re in one. We came from one. We’re going to one. They mean, well, something. Nothing. Everything. As redhead Cynthia Dunn says while cruising around a car just vibing as a 1970s teenager in Dazed and Confused:

“The fifties were boring. The sixties rocked. And the seventies—oh my God, they obviously suck. Come on! Maybe the eighties will be radical.”

The joke plays on the audience’s foreknowledge of the actual 80s, and I like it not just because it’s said by one of my childhood crushes in one of my favorite movies, but because there are plenty of real actual academic theories based on (essentially) decade changes, from the Strauss–Howe generational theory to cyclical theory.

Besides, we all know decades have vibes. That’s why Dazed and Confused, a movie famous for having a meandering plot, no plot at all really, works so well. And if decades have vibes this logically implies that, within decades, there are years that represent certain vibe shifts. As Charles Schifano recently wrote:

Annie Ernaux, who was twenty-eight in 1968, encapsulates the narrow sensation nicely in The Years, stating that “1968 was the first year of the world.”

Annie Ernaux may have been right; perhaps, in a way, she’ll always be right. But for us, for our decade, for our current vibe: what year was it established? When was the decade-defining great vibe shift? What was the first year of our particular world?

The answer is actually rather clear. For whenever I now see a graph plotting out something by years, my eyes now jump to a certain date: 2012. And, more often than not, there is evidence of some kind of fulcrum there. Others have also started to take notice as well: 2012 was a “tipping-point” year.

Such a year can mean a lot of things. Some tipping-point years are cultural, like 1968 (the Tet Offensive, MLK assassination, Robert Kennedy assassination, Civil Rights Act, Star Trek airs the first interracial kiss, all of which established the vibe of the coming 1970s). Other tipping-point years are economic, like 1971. In fact, there’s even www.wtfhappenedin1971.com which lays out chart after chart showing how there were sudden disruptions of long-running economic trends in America.

The website includes dozens of examples of 1971 being a tipping-point year, and not everything is just an economic metric:

The cause of the 1971 changes is debated extensively, like asking: Why did the Consumer Price Index shoot to the moon right after 1971?

In comparison, 2012 appears to be more like 1968 in that it marked changes primarily cultural and psychological, not economic. Of course, we should expect it to be harder to measure cultural tipping-point years rather than economic ones, since what makes for healthy psychologies and cultures is often immeasurable. Still, if you look at charts about people’s psychology, or culture in general, like how people use language, you often consistently see a major shift around 2012 or shortly thereafter.

This isn’t just due to the definition of the word “depression” broadening. Teenagers legitimately try to commit suicide far more now, taking off right around 2012.

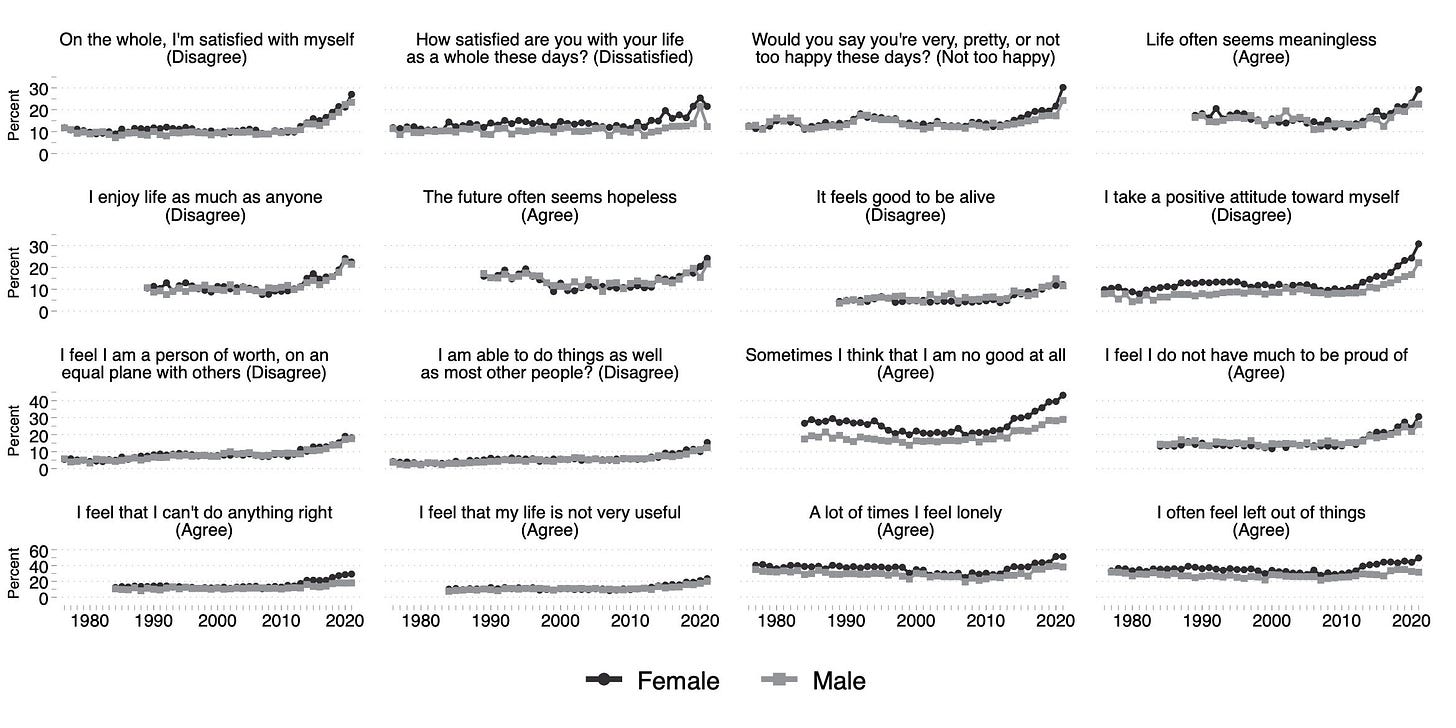

These changes haven’t affected just teenagers, although they are the most intense there, as if the youth, those most exposed and dependent on the current culture, those with nothing else to lean back on (no memories of the 90s to bask in) are operating like canaries in a coal mine—it is their little lungs which go first. A recent article in American Affairs Journal writes that:

Between 2012 and 2015, the number of teens failing to get seven hours of sleep per night increased by 22 percent, ultimately meaning that by 2015 a full 57 percent more teens were sleep-deprived than in 1991; presently, 60 to 70 percent of American teens “live with a borderline to severe sleep debt.” After 2012, the proportion of teens who regularly skip breakfast spiked from around a quarter to a third. Between that year and 2015, Twenge writes, “boys’ depression increased by 21% . . . and girls’ increased by 50%,” while between 2007 and 2015, the suicide rate among twelve-to-fourteen-year-olds doubled for boys and tripled for girls.

See, e.g., the responses of 12th graders about their mental health changing over the decade.

Although it’s certainly clear the cultural vibe shift of 2012 affected adults as well.

And yes, psychological changes are nebulous, but there are obvious downstream real-world ramifications. For 13-year-olds across America, both reading and mathematics peaked in 2012 and then rapidly began to decline.

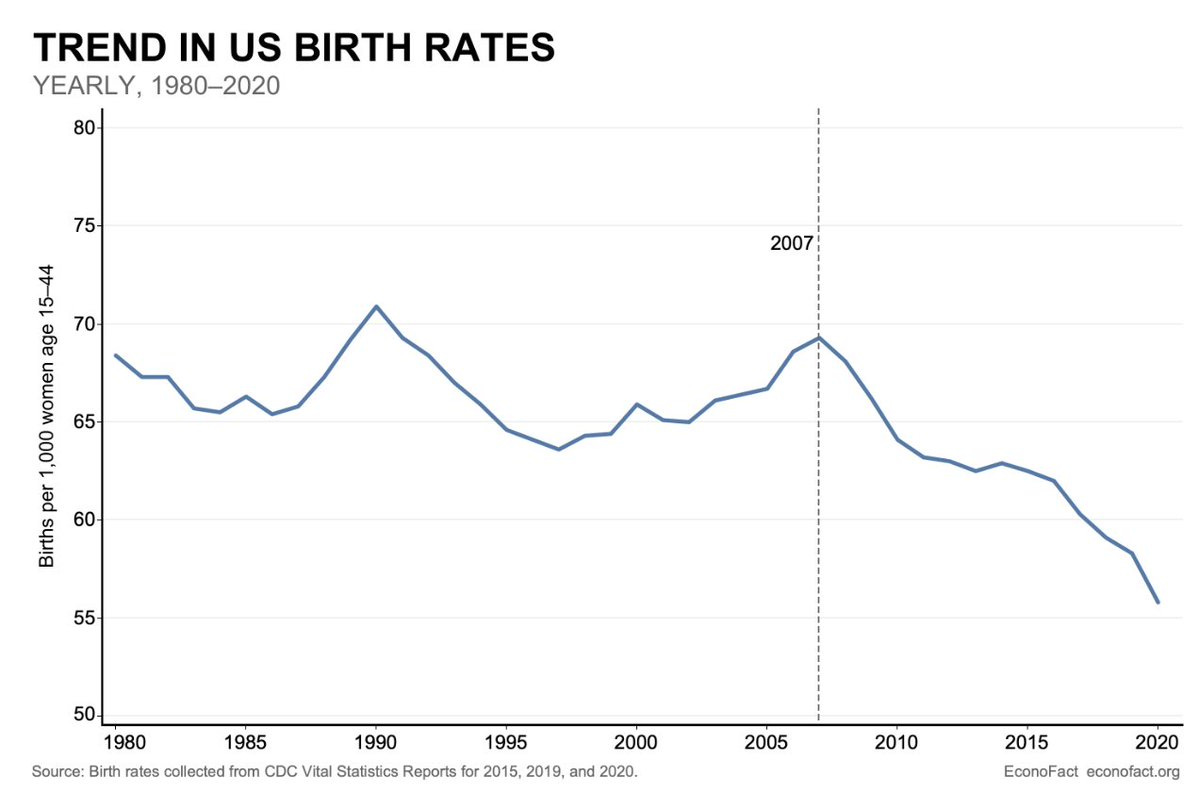

Around 2012, birth rates fell off. They were low anyways, which should be expected after the Great Recession, but it is precisely around 2012 where they should have started climbing back up and instead they fell off a cliff.

Perhaps one of the biggest changes ever of how couples actually meet occurred in 2012 as well.

Psychological changes were accompanied by cultural ones. Following 2012 culture itself became more depressed, anxious, and angry. There are even changes to how hardcore chart-topping songs are:

Around 2012, the proportion of movies that are remakes, or part of series, having effectively plateaued since around 2000, began to climb to new heights of unoriginality.

Most of the cultural issues that continue to dominate the public discourse started to take off precisely around 2012, if we are to judge by word frequency:

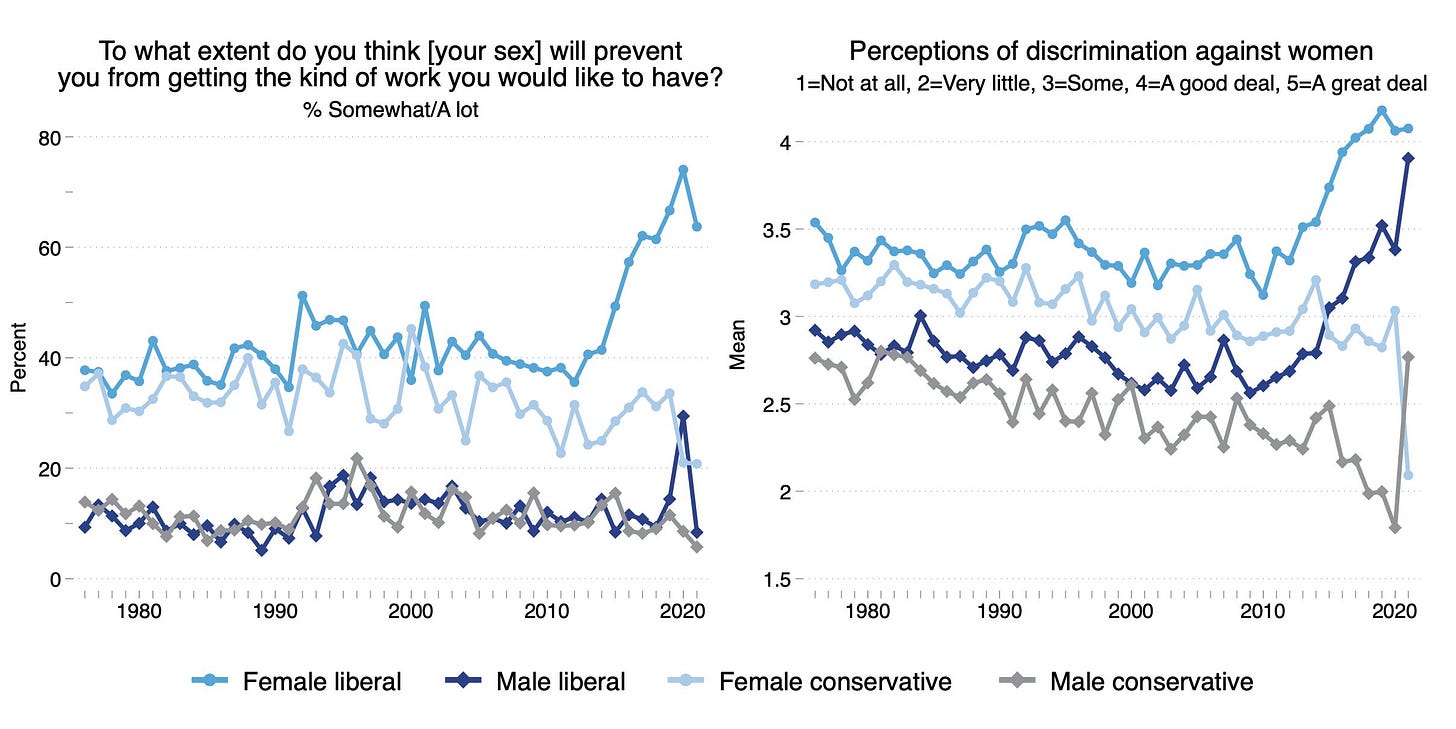

It’s simply impossible to dance around it: what would now be called “wokeness” came onto the main stage of culture in 2012, and this in turn began to trigger anti-wokeness (e.g., while Jordan Peterson wouldn’t become famous until 2016, 2013 was when he created his YouTube channel and began uploading). This action/reaction dynamic explains the timing differences for when each political side felt the psychological effects.

This is true for, e.g., perception of discrimination, which rose rapidly around 2012 as well.

At a personal level, I remember someone in graduate school, which I entered in 2010, confessing to me after a few beers that the rise in politicalization among our peers around 2012-2013 (as my fellow grad students either suddenly bought into wokeness and started using its reasoning and language or staked out controversial or secretively resistant anti-woke positions) reminded him of “the invasion of the body-snatchers.” His theory was that the body-snatching was happening through their phones.

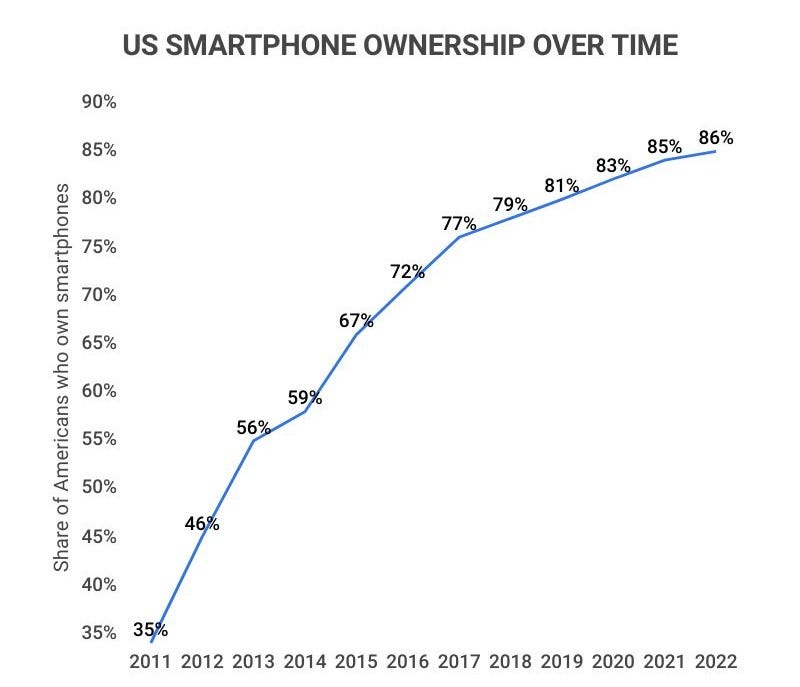

My friend would not be surprised to learn that the major political reorientation of the decade sprung into existence the second everyone got smartphones.

In fact, in terms of market saturation, the transition from 2012 to 2013 is the exact year the majority of the US switched to finally owning a smartphone.

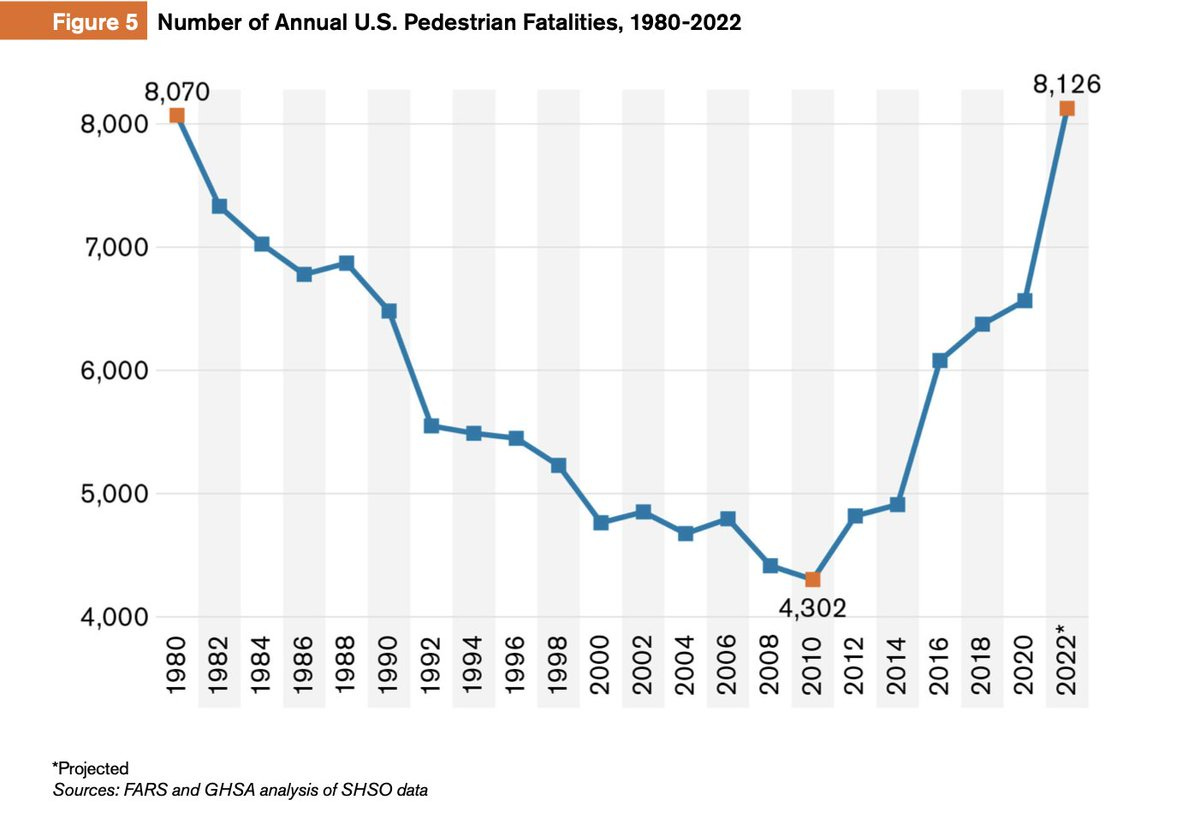

Which would certainly explain the massive spike in pedestrian fatalities from cars following a low in 2010.

The point to all this is just to make explicit what I think so many already know and feel: if we were forced to pinpoint a year, 2012 appears to be a good choice for when the modern world was invented, and we’ve been living in it now for a little over a decade.

And to go back to the decade theory: certainly it’s arguable that, ten years into existence, our world feels, at least in terms of vibes, very similar to the world at the end of the previous cultural revolution of the 1960s. Even just politically, while the cultural revolution of 2012 grained a great deal of ground in institutions, it has spent much of its initial momentum, and is being combated institutionally by, e.g., the Supreme Court’s recent decision to ban affirmative action. A fundamental detente has been reached. The cultural revolution that people now call “wokeness,” and the debates around it are still ever-present, but also feel somewhat spent.

The degree to which this is true can be judged by one cultural artifact in particular: Barbie. The movie. For yes, the biggest movie of the summer is about patriarchy, and its openly political plot and language and messaging would have contained a lot of academic gobbledegook for the average citizen in 2011. But, at the same time, the movie is a clear commercialization about a toy, and can be interpreted ambiguously, parodying itself; ripe for interpretation, it has been championed by liberals and conservatives alike. See how, for instance, that even within that most conservative institution, The Daily Wire, there is disagreement on whether Barbie is actually a left-leaning movie (as Ben Shapiro believes) or, secretly, a subversively right-leaning movie (as Michael Knowles believes). The confusion over the messaging of Barbie is a synecdoche for the confusion over our own post-revolution world, which now looks corrupt and run-down, much like the depressive “malaise” of the 1970s.

Indeed, Noah Smith recently explicitly made the comparison of the modern day to the 1970s:

Economic confidence is low despite rapid growth and high employment rates — the so-called “vibecession”. Much of that pessimism is probably due to the decline in real wages last year, but some might be a spillover from social divisions. Approval ratings for both parties and all major national politicians are in the toilet. Jimmy Carter’s famous “malaise” speech from 1979 (which did not actually contain the word “malaise”) seems somewhat applicable to the national mood of 2023.

If the cultural revolution of the 1960s was followed about a decade later by an economic shift in 1971, one has to wonder if history will repeat so obviously, with Biden playing the role of Jimmy Carter, having followed up a president, Nixon, who had articles of impeachment filed against him. Perhaps this is the recent “vibe shift” people on The Social Media Platform Formally Known as Twitter have been referencing, which is essentially just an exhaustion of the debates that started in 2012.

Surely, things must be more complicated than these decade theories, no? Of course. Obviously so. As a level of analysis they are nearly mystical. But if you had used this model of [cultural revolution → inflationary period→ lasting economic and cultural malaise] back 2012 I think you’d have a claim to near-Nostradamus levels of precognition. And that third stage would predict, much like the post-1971 world, a coming permanent change in long-standing economic trends (followed, potentially, in the 2030s with the return of Big Hair, leg warmers, and cocaine).

If we are to spend the 2020s mirroring the 1970s, and therefore occupied with domestic turmoil as the post-revolution cultural tremors play out, I suppose we might as well begin to ape it as much as possible.

Well you note that 2012 was the year that smartphone usage crossed the 50% threshold. Guess what? 1972 is the year that more than 50% of households had a color TV for the first time.

When 50% of the population adopts a new technology, what that really means is that virtually EVERY urban and adolescent-middle aged person has it. It just takes a few more years before the rural people and 70 years olds get there.

Transitioning to a society where suddenly you got to look at in color, moving images of drama and beautiful people and constant advertising was a cataclysmic change. For the first time, you weren't comparing yourself to people in your neighborhood or school or at work. But to actors and models who were there all the time, in your own living room. TVs are desire and comparison machines, providing mesmerizing images of all the ways your life could or should be, and all the stuff you should have. It's when we became more self-centered, more greedy, more inwardly focused, and less likely to go out to the bar or sit on the porch or play cards with neighbors, and instead sat inside watching strangers on TV. You can trace basically everything in those 1971 charts to that, from obesity to no more labor unions to more divorce. TVs also made people more tolerant and less provincial, as they saw sympathetic portrayals of all kinds of people and got more used to people who are different from what they might come across in real life.

Smart phones did all of the same things, but multiplied by a factor of 10. Now we all get to see everything and everyone in the world, half of it fake, much of it either horrifying or fantasy. Our brains aren't evolved for this.

So, that's a pretty simple and clear cultural theory. Though I could give a pretty simple and clear economic theory regarding 1971. Which is simply that that is the year that the labor supply began a sharp upward tick from the lows of 1940-1970. We had almost no immigration in those years, and the immigrant share of the population plunged from the high teens down to a low of about 5% in 1970, then back up to the high teens again today. Women hadn't yet entered the work force in droves, and started in the 70s. And all those kids the baby boomers had in the 40s-60s hadn't yet grown up and went to work. So the labor supply was incredibly low in those decades, and low supply of labor means lots of leverage and bargaining power, so naturally we saw the lowest income inequality that ever existed in those years. More women, more immigrants, and more kids turning working age starting in the 70s and accelerating over the next few decades vastly increased the size of the workforce. More workers means way more competition and way less power, so of course wages stagnated and everything else bad we've seen economically, with those at the bottom hit the worst.

Didn’t the Mayan calendar warn us about this? We’ve just been running around with our heads cut off ever since