FTX: Effective altruism can't run from its Frankenstein's monster (free version)

Sam Bankman-Fried embraced the hardcore ideals of EA

This is a free version of the first post for paid subscribers of TIP. I’ll occasionally send out such versions so free subscribers can see if they’d like to upgrade their subscription, as my goal is writing that’s worth the upgrade.

“‘Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other and trample upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember that I am thy creature.’”—Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

The person supposed to be the “first trillionaire” is, in many ways, a creation. Sam Bankman-Fried, affectionally known as SBF, was until recently effective altruism’s biggest funder, to the tune of not just a promised 24 billion dollars, but all his future trillions. And then, as has been discussed nearly everywhere, the FTX Cryptocurrency Exchange, which he is CEO of, stopped allowing withdrawals and all those billions and potential trillions went up in smoke, along with all his customer’s money. If in a decade barely anyone uses the term “effective altruism” anymore, it will be because of him. Imagine if Elizabeth Holmes had been the primary donor to the effective altruism (EA) movement, and that Theranos had been created specifically by the EA movement, and you can get a sense of what just happened.

It may at first seem overblown to say SBF was a Shelley-esque creation of EA, but FTX itself was essentially made in a lab in order to donate the most money to charity, to save the most lives. Here’s from a Forbes profile:

[SBF] read deeply in utilitarian philosophy, finding himself especially attracted to effective altruism. . . An effective altruist looks to data to decide where and when to donate to a cause, basing the decision on impersonal goals like saving the most lives, or creating the most income, per dollar donated. One of the most important variables, obviously, is having a lot of money to give away to begin with. So Bankman-Fried shelved the notion of becoming a professor and got to work trying to amass a world-class fortune.

Even the personnel of FTX were a direct outgrowth of the movement. Here’s Nishad Singh, an inner-circle member of FTX:

This thing couldn’t have taken off without EA. All the employees, all the funding—everything was EA to start with.

And the philosophy of the company’s approach was also based in EA:

To be fully rational about maximizing his income on behalf of the poor. . . [SBF] felt he needed to take on a lot more risk in the hopes of becoming part of the global elite. . . To do the most good for the world, SBF needed to find a path on which he’d be a coin toss away from going totally bust.

Where can you always be a coin toss away from going totally bust? Cryptocurrency! So FTX being a crypto exchange was a logical choice that SBF made based on EA. Heck, they even said so on their ads.

Personally, I’ve always had a soft spot for EA, as they’ve brought a lot of attention to causes I think are important. Particularly AI safety. And, like everyone, I think charitable giving is, you know, good. So members of EA have my sympathy; the individuals who trusted SBF personally, along with the everyday rank and file, all got sucker punched last week. The fact that billions promised in charity have evaporated is a loss for the world.

But I’ve also harshly critiqued the movement, like in “Why I am not an effective altruist,” where I argued EA had a dangerous tendency to take utilitarianism too literally. And now it appears that some members of EA. . . took utilitarianism too literally. For an organization all about ethics, it’s especially problematic since FTX money reaches deep into the movement’s charities and non-profits, and that’s just from what’s known publicly (there was untraced FTX money flowing around, I know because I was once sent a small amount: more on this later).

Now, pretty much everyone in the broader EA movement who received FTX money knew next to nothing about the level of financial risk SBF was taking on. If you’re looking for clairvoyant knowledge of FTX’s impending collapse inside EA, you likely won’t find it.

The question is not: did anyone in EA (outside of the EA members of FTX) know about its shady dealings? The question is: was the FTX implosion a consequence of the moral philosophy of EA brought to its logical conclusion? This latter question is why some people are trying to create as much distance between SBF and EA as possible.

The first attempt at distancing FTX from EA comes via the narrative that SBF didn’t know “how to properly EA.” E.g., that he took a radical non-mainstream interpretation of the movement, or was ignorant of details, etc. The second, more recent narrative, is that SBF is a sociopath who only used EA for cover. The first narrative is provably untrue. The second, a character judgement about hidden motives, is harder to falsify, but rests on shaky and conspiratorial foundations, like a screenshot of a couple curt and highly ambiguous text messages.

So, first’s first: did SBF know how to EA? For instance, perhaps if SBF had only known about “rule utilitarianism” this would have prevented FTX’s implosion—many people have responded like this on Twitter. (Rule utilitarianism being the idea that people should follow the set of rules that maximize good, rather than judging each individual action independently). Here’s a succinct version by Scott Alexander at Astral Codex Ten in reaction to the FTX revelation:

. . . in most normal situations following the rules is the way to go. This isn’t super-advanced esoteric stuff. This is just rule utilitarianism, which has been part of every discussion of utilitarianism since John Stuart Mill.

This is why, e.g., William MacAskill (who, according to The New York Times, originally pitched a college-aged SBF on “earning to give”) and other EA leaders are digging up statements they’ve previously made like "plausibly it’s wrong to do harm even when doing so will bring about the best outcome.”

The problem is that SBF has been crystal clear about his philosophical beliefs for years, if not decades, and knew all this stuff and had good arguments on his side. Here’s SBF on his blog, which is mostly about utilitarianism, way back in 2012, long predating any fame:

I am a utilitarian. Basically, this means that I believe the right action is the one that maximizes total "utility" in the world (you can think of that as total happiness minus total pain). Specifically, I am a total, act, hedonistic/one level (as opposed to high and low pleasure), classical (as opposed to negative) utilitarian; in short, I'm a Benthamite.

This jargon means that SBF occupies a well-defined position within utilitarian philosophy, which is that being moral means taking the action that maximizes the expectation of the pleasure/happiness (“hedonistic”) of the maximum number of people (“total”), and that one should calculate this based on each action (“act”), not rules. This also describes his approach to EA, as SBF interchangeably referred to “effective altruism” as “practical utilitarianism.”

And, guess what, SBF wrote an entire blog post about why he’s an “act” instead of a rule utilitarian! He gives the classic rejection of rule utilitarianism, which can also be found on Wikipedia:

It has been argued that rule utilitarianism collapses into act utilitarianism, because for any given rule, in the case where breaking the rule produces more utility, the rule can be refined by the addition of a sub-rule that handles cases like the exception.

So if someone brought it up to SBF, he would probably immediately reply: “Wouldn’t rule utilitarianism simply mean advocating for making what I did legal, assuming it was in the service of good?” He’d have such a whip-quick answer because he was familiar with all these debates (and btw, we’re still not even sure about the level of legality here).

The harsh reality is that SBF was an MIT student with two Stanford professors for parents, and over years he carefully considered different versions of utilitarianism, carefully considered different ways to weight his utility calculations, and these careful considerations led him to FTX.1 His ideas about utilitarianism were within the mainstream. Exactly like William MacAskill, who teaches a course at Oxford on utilitarianism, who has said he accepts some of the repugnant moral conclusions of utilitarianism, and who co-wrote the website utilitarianism.net. And while MacAskill is more ambivalent than most (he even has a book admirably called Moral Uncertainty), some of the founders of EA have explicitly advocated for the most extreme utilitarian stances—in a way, counterintuitive ethical examples are the big selling point of academic moral philosophy. Is it really foundational to EA that simple deontological principles, like not to lie, or even just risk user funds via shady crypto coins, completely trumps utilitarian considerations? For anyone familiar with the tone and content of the movement’s literature and discussions, this strains credulity.

Also within the mainstream was SBF’s idea of maximizing the expected value of his giving via risky business ventures. Here’s him with EA leader Rob Wiblin from 80,000 Hours:

Sam Bankman-Fried: . . . Even if we [FTX] were probably going to fail, in expectation, I think it was actually still quite good.

Rob Wiblin: Yeah.

Or, in plenty of cases, it was the EA leaders who laid out reasoning about risk taking, and SBF was the one nodding.

Rob Wiblin: But when it comes to doing good. . . you kind of want to just be risk neutral. As an individual, to make a bet where it’s like, “I’m going to gamble my $10 billion and either get $20 billion or $0, with equal probability” would be madness. But from an altruistic point of view, it’s not so crazy. Maybe that’s an even bet, but you should be much more open to making radical gambles like that.

Sam Bankman-Fried: Completely agree.

In conclusion: none of SBF’s beliefs seem particularly unusual by EA standards, except that he took these principles to such literal extremes in his own life.

Let’s say you’re walking next to a shallow pond, and in it is a drowning child. You happen to be wearing an expensive suit you borrowed. Do you go into the pond to rescue the child and therefore take the chance on ruining the suit that’s not yours?

After proposing this to you, EA’s monster lays his discolored hand on your shoulder. “Okay,” he says in a gravelly voice made of different throats, “Now scale that up and don’t ever ever stop.”

Just like in the moral philosophy thought experiments that EA is based on, SBF dove into the pond. SBF pulled the lever in the trolley problem. SBF became the serial killer surgeon, willing to butcher the few to save the many.

SBF was a very effective altruist. At least, in expectation.

What about the second narrative that attempts to distance SBF from EA? Maybe SBF was a sociopath who never really believed?

Occam’s razor is, as razors are built to be, unkind to this. For, despite the rumors swirling on Twitter, there’s no good evidence that SBF was using EA as a front.

An aspect that would at least support the “sociopath using EA a front” narrative would be if the FTX blowup was based on very obvious criminal and/or selfish acts. The evidence for this is confusingly mixed with the inevitable rumors that fly following any public figure’s blowup. What’s known for sure is that FTX got too deep in debt and did so in shady ways (which were described thusly in the original Coindesk investigative article that kicked off everything):

That balance sheet is full of FTX – specifically, the FTT token issued by the exchange that grants holders a discount on trading fees on its marketplace. While there is nothing per se untoward or wrong about that, it shows Bankman-Fried’s trading giant Alameda rests on a foundation largely made up of a coin that a sister company invented, not an independent asset like a fiat currency or another crypto.

So, I think it worked: People sent FTX money. Like most exchanges, FTX doesn’t just hold onto that money. It was a fractional reserve, like your own bank—it owns assets that offset its liability (what it owes you). The problem is that FTX’s assets had a bunch of cryptocurrency it issued itself (FTT), which was illiquid. SBF sent that FTT to Alameda to save it. This got noticed. People started selling FTT. Soon it was worth nothing and so was the exchange. Maybe more shady things happened, but frankly no one knows for sure, as far as I can tell.

There’s been speculation about whether SBF’s risky trading behavior was driven by drugs, except that we don’t know if he was on drugs, and the scientific connection with risk-taking behaviors for the drugs we don’t even know if he was on are themselves weak, and most of Wall Street does stimulants anyways, etc. While I’m no expert, it does seem possible that in many worlds FTX never goes bust. SBF misuses users funds, sure, takes on way too much debt, sure, but maybe Coindesk never does their original investigative article into FTX that started the rumors about FTT, maybe the CEO of Binance never goes on Twitter to say he’s selling their FTT because of it, or when he does he chooses less alarming language than that it was “due to recent revelations that have came to light.” Instead, FTX just goes through a dangerous vulnerable spot that no one really notices and then all their risk-taking pays off and in ten years SBF can donate not just 24 billion dollars, but a trillion dollars. So SBF may have had, from an “expected good” perspective, reasons to do what he did. As a prominent EA member put it in a now deleted tweet (unsourced to preserve anonymity):

You bet big, you sometimes lose.

Without the direct concrete proof that SBF was acting selfishly, the latest way for EA to run from their monster is to claim that SBF never believed any of it. That all his decades-long talk about EA and utilitarianism, all his own writing before he was famous, was just a clever long-built shield. The evidence for this mainly comes from a journalist, Kelsey Piper, who recently leaked some partial screenshots of curt and ambiguous texts by SBF.

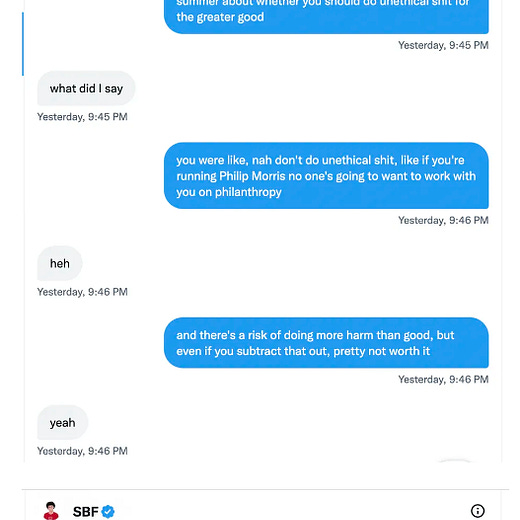

Who’s Piper? She is a senior writer at the effective altruism section of Vox (yes, they have a dedicated section). She’s a self-identifying effective altruist around Sam’s age, and she and SBF appear to have known each other socially (SBF said he assumed they were just texts with a friend). It appears some of the text in-between the screenshots was cutoff, so it’s likely selective slices, as I can’t find any evidence that these reflect the full transcript in order, etc. There’s one particular line that people have latched onto, hoping that the monster wasn’t really created from EA, he just found EA.

Piper: So the ethics stuff - mostly a front? people will like you if you win and hate you if you lose and that’s how it all really works?

SBF: yeah. I mean that’s not *all* of it. but it’s a lot. the worst quandrant is “sketchy + lose.” the best is “win + ???”

There’s a couple issues with this. First, it’s a double question—is SBF responding to the first one? His response makes more sense to the second one, about if people will like you if you win (from the context, it appears he might be talking about making money via an exchange or doing good as “winning”). And what does he think she means by “the ethics stuff?” It’s very possible he assumes she’s referring to earlier in the exchange, as Piper starts this topic by saying she was “relistening to that conversation we had this summer about whether you should do unethical shit for the greater good” where SBF had said that you shouldn’t do unethical shit for the greater good. Which in turn, means SBF is saying he never believed that people shouldn’t do unethical shit for the greater good! That’s what was the front. Following the rules. Which would fit perfectly with what we know about him. A number of people have noted this:

A post on the LessWrong forum reads the exchange thusly:

This seems to give some credit to the theory that SBF could have been acting like a naive utilitarian, choosing to engage in morally objectionable behavior to maximize his positive impact, while explicitly misrepresenting his views to others.

That’s also how I read it. Piper herself admits it was ambiguous:

So, while perhaps SBF really was renouncing all of EA via a “yeah” to a text to a friend who is a self-identified EA, I think this is just not understanding the ambiguity of texted communication, the partialness of the evidence, or even, I hate to say it, the biased nature of the screenshots’ origin (which kinda seem a deontological violation in order to do the greatest good and protect EA—perhaps it’s turtles all the way down).

I’m sure plenty will latch on to the convenient excuse that “it was all a front,” even if it contradicts everything else SBF has ever written or produced—that it was the longest con. But the far less assumptive answer to what happened appears to be, barring further data, merely that moral philosophy met the real world, and moral philosophy lost.

There’s now a ton of practical problems for EA. In cryptocurrency there is the idea of “tainted coins.” These are coins that have been associated with illegal activity. A lot of exchanges don’t take them. Analogously, FTX money is now tainted money, at least, ethically.

And FTX money has been hard to track. I know because I was once handed $6,500 from the FTX Future Fund, the donation arm of FTX, and they never announced it. This occurred about eight months ago. It’s the only money I ever received from EA. I had read there was a charity organization interested in giving money to blogs from a post on Tyler Cowen’s Marginal Revolution, so, while knowing essentially nothing about it, I randomly sent a brief application to Future Fund’s grant program for $6,500 to help me write this newsletter.

There’s no actual public evidence of their gift to me. A search on the FTX Future Fund grant website turns up nothing. I myself announced it on Twitter when it happened, thinking I was part of the official FTX Future Fund grant program. I kept waiting for them to mention the donation somewhere. They never did. At least, not that I ever found. I always felt it was weird how silent and fast it had all been.2

Users who had their savings stolen by FTX are now scrambling for legal recourse. Do you think Tom Brady, an FTX investor, is going to let millions of dollars vanish into thin air? He doesn’t strike me as someone who likes to lose. I can’t see anything but gridlock.

Why does this all matter? Well, it’s an interesting reminder of what’s always unavoidable, which is human nature. Some of the EA leaders at the tippy top have been enriched in their careers over the last decades, if not by money than by reputation (I’m talking about an incredibly small number of people here, like those who run major EA organizations, not everyone involved with or even prominent in EA). Many of these leaders gave a chunk of their salary away, but the story is actually more complicated, like a Catholic bishop dripped out in jewelry saying “Well, I only earn a small pittance.” Here’s where SBF, the great altruist, actually lived:

At an abstract and brutal level, is there much of a difference between this and how William MacAskill’s bestselling last book got written (from my review)?

. . . not many books have three “chiefs of staff” that led the team that worked on the book, nor two different “executive assistants,” nor four “research fellows,” nor an additional host of “regular advisors,” all of whom MacAskill himself credits as “coauthors.” The publicity of the book has been just as well-crafted as the text, so much so that it’s hard to name a major media outlet that hasn’t written about it. . .

I’m not crowing over this. I’m not secretly happy that utilitarianism got its comeuppance. I’m not happy individuals had their lives implode. Most people in EA, even the EA leaders I’ve been hard on here, like MacAskill, have simply been trying to do good. But my ultimate take away is this: when you tell young people they can have a major impact, they listen. “You’re going to change the world” is a strong pitch, made stronger if you also tell them that getting rich will make them saints, make them literally worth more, and that along the way you can teach them to be hyper-rational and logical about it all and see, as if by a third eye, the objective truth.

Perhaps inevitably, a young college-age elite with a lot of potential and connections came along, and he ended up coming to the logical conclusion that EA should be taken as seriously as possible, and this, mixed with hubris borrowed from Wall Street and risk borrowed from crypto, was likely the Aristotelian formal cause of FTX’s collapse.

That’s why I think EA never recovers. Oh, many EA charities might be active in ten years, I don’t doubt. I certainly hope so, as in their outputs they often do a lot of good. But the intellectual and cultural momentum of EA will be forever sapped, and EA will likely dilute away into merely a set of successful institutions, some of whom barely mention their origins.

Ideas are powerful. The idea of being super-moral, super-rational, better than other people, of being worth more than other people—these are all like inhaling pure oxygen for the young, and EA has been pumping out this oxygen for years now.

And oxygen is flammable.

In addition to the “He forgot about rule utilitarianism” reply there’s also the idea that SBF left out too much in his calculations of the expected moral value of his actions, so they don’t count. E.g: “If only SBF had included the damage to utilitarianism that exposing the repugnancy of utilitarianism could do in his calculations, he would never have done it!” (Hint to why this is wrong: it's not a good moral philosophy where you have to be constantly careful of people realizing what the philosophy recommends).

Of course, both public and secret recipients should return Bankman’s FTX money to the those who were robbed, if that’s possible. That’s what I support, although this early on I have no idea how this happens from a practical perspective, or even if there’ll ever be a secure way to.