Polymaths are back from the dead

AI's resurrection of an extinct breed of intellectual

Polymathy, everyone knows, went extinct in the second half of the 20th century. Only a few intellectual giants—names like Bertrand Russell, John von Neumann, or Michael Polanyi—kept its veins flowing with blood until they themselves finally flatlined, and it did too.

Perhaps more was lost than we’d like to admit. After all, the few fragile centuries of the Enlightenment, which was when our reigning political order was established, and when our major institutions were defined, and when modern science itself came to be, all occurred during the time when polymaths ruled the earth (well, as much as intellectuals ever do).

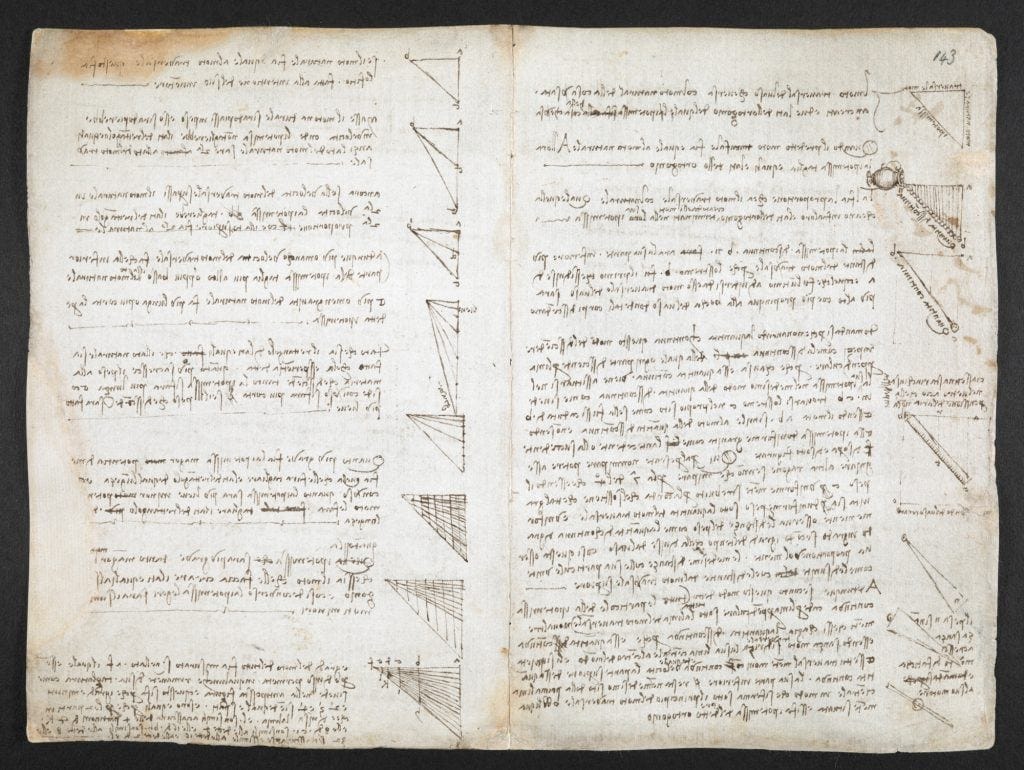

It's hard to overstate how fecund the most famous polymaths were. We stare at their journals like the bones of extinct creatures. Consider how recent analysis of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook (his “Codex Arundel”) revealed da Vinci had worked out gravity not only pulls things down but, far more fundamentally, actively accelerates the downward pull at a particular rate—the key to understanding the entire phenomenon! And it was knowledge unlocked as a side-project by an artist a century and a half before Newton. According to the physicist who noticed:

… with this drawing da Vinci managed to estimate what is known to physicists as the “gravitational constant” within ten percent of its actual value, despite only conducting what appears to have been a crude experiment.

However famous da Vinci is now, he was close to being far more so.

But it was in the air. And just as much so for all the contributing lesser-known figures only historians now remember. E.g., “The polymath in the age of specialisation” in Engelsberg Ideas lists many polymaths who are not household names, along with their expansive expertises, like Athanasius Kircher (“ancient Egypt, acoustics, optics, language, fossils, magnetism, music, mathematics, mining and physiology”), Olaus Rudbeck (“anatomy to linguistics, music, botany, ornithology, antiquities and what we now call archaeology”), Benito Jerónimo Feijóo, a Spanish monk (“known in his day as a ‘monster of erudition’ in the 17th-century style… The nine volumes of his Teatro crítico universal dealt with ‘every sort of subject’”), Pierre Bayle (“wrote mainly about theology, philosophy and history, but also edited a learned journal, the Nouvelles de la République des Lettres, and compiled an encyclopaedia, the Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, in which the footnotes took up more space than the text because he filled them with critical remarks of his own”), Comte de Buffon (“remembered today for the huge enterprise of his Histoire Naturelle, published in 36 volumes, was also active in the fields of mathematics, physics, demography, palaeontology and physiology”), and so on and on.

The cause of death of the polymath is universally agreed-upon: increasing demands of specialization rendered polymathy impossible. There became too much to know. “Whatever happened to the polymath?” in UnHerd summarizes the postmortem:

The decline of polymathy… is a crisis of too much information. The seventeenth century was a “golden age of polymaths”, as explorers found new regions, the scientific method flourished, and the postal service and the proliferation of journals allowed scholars to trade ideas. But those same forces led to “information overload.” Over the next 200 years, the intellectual world divided between the specialists who knew a lot about their little area, and popularisers who knew a little about a lot.

Today, a “polymath” is at most someone who studies a few separate areas of mathematics—or who can both direct a movie and act in one. But in just 1870, it meant someone like Lewis Carroll, who you likely know as the author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, yet who was also a poet, a photographer, a literal deacon, and he wrote nearly a dozen books on mathematics spanning algebra to probability to logic, and he invented “word ladder” puzzles.

As Peter Burke, a historian at Cambridge University and author of The Polymath: A Cultural History, lamented a few years ago:

Younger polymaths are becoming more difficult to find… I am unable to identify any who were born after the year 1960. Will the species become extinct?

To answer Burke, there are a few names I could give from after 1960, but in general he’s correct. If da Vinci were resurrected to look upon his intellectual descendants, modern thinkers would surely strike him as species warped by the pressures of hyper-specialization. Our academia is now populated by minds pressured into shapes as niche as hummingbirds (upon whom evolution forces the dubious delicacy of only eating nectar) or fig wasps (destined to birth their young solely within the sticky-sweet confines of a single species of fruit, one which they presumably call, in their native Hymenopterian, simply “mother.”)

So is polymathy’s decline just a law of intellectual nature?

To put it simply: there are two kinds of thinkers. Those rate-limited by expertise, and those rate-limited by creativity. Slowly but consistently, the rate-limiting factor for intellectual contribution has become ever deeper expertise.