The Internet You Missed: A 2025 Snapshot

TIP's community writing: Part 1 of 2

There are many internets. There are internets that are bright and clean and whistling fast, like the trains in Tokyo. There are internets filled with serious people talking as if in serious rooms, internets of gossip and heart emojis, and internets of clowns. There are internets you can only enter through a hole under your bed, an orifice into which you writhe.

It’s a chromatic thing that can’t hold a shape for more than an instant. But every year, I get to see the internet through the eyes of subscribers to The Intrinsic Perspective. The community submits its writing available online, and I curate and share it.

The quality was truly exceptional this year—I found that they all speak for themselves, and can all be approached on their own terms, so I organized them to highlight how each is worth reading, thinking about, disagreeing with, or simply enjoying; at the very least, they are worth browsing through at your leisure, and finding hidden gems of writers to follow.

Please note that:

I cannot fact check each piece, nor is including it an official endorsement of its contents.

Descriptions of each piece, in italics, were written by the authors themselves, not me (but sometimes adapted for readability). What follows is from the community. I’m just the curator here.

I personally pulled excerpts and images from each piece after some thought, to give a sense of them.

If you submitted something and it’s missing, note that it’s probably in an upcoming Part 2.

So here is their internet, or our internet, or at least, the shutter-click frozen image of one possible internet.

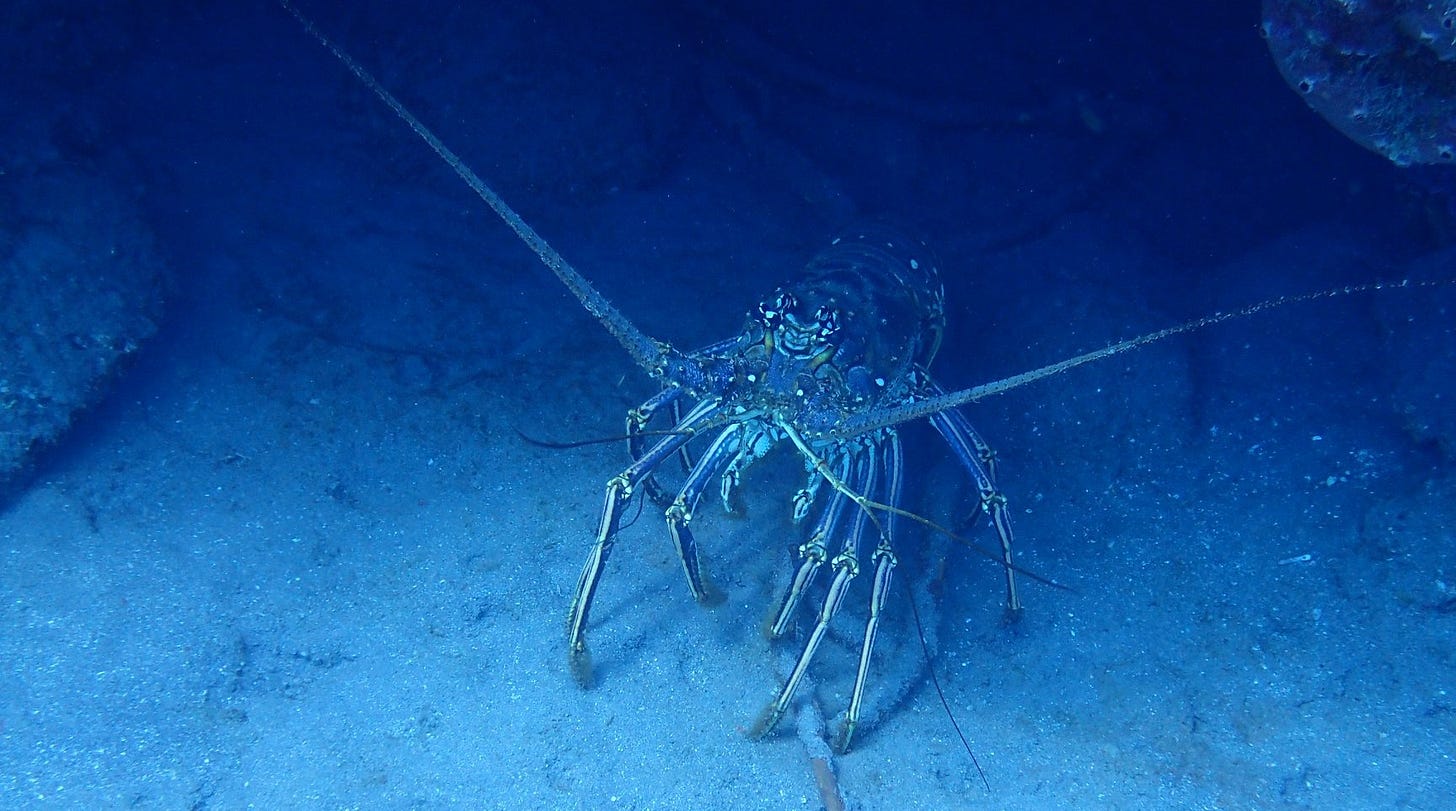

1. “Wisdom of Doves” by Doctrix Periwinkle.

Evolved animal behaviors are legion, so why do we choose the examples we do to explain our own?

According to psychologist Jordan Peterson, we are like lobsters. We are hierarchical and fight over limited resources….

Dr. Peterson is a Canadian, and he is describing the North Atlantic American lobster, Homarus americanus. Where I live, lobsters are different.

For instance, they do not fight with their claws, because they do not have claws…. Because they do not have claws, spiny lobsters (Panulirus argus) are preyed upon by tropical fish called triggerfish…. The same kind of hormone signaling that made American lobsters exert dominance and fight each other causes spiny lobsters to cluster together to fight triggerfish, using elaborately coordinated collective behavior. Panulirus lobsters form choreographed “queues,” “rosettes,” and “phalanxes” to keep each other safe from the triggerfish foe. Instead of using claws to engage in combat with other lobsters, spiny lobsters use their attenules—the spindly homologues of claws seen in the photograph above—to keep in close contact with their friends….

If you are a lobster, what kind of lobster are you?

2. “We Know A Good Life When We See It” by Matt Duffy.

A reflection on how fluency replaced virtue in elite culture, and why recovering visible moral seriousness is essential to institutional and personal coherence.

We’ve inherited many of the conditions that historically enabled virtue—stability, affluence, access, mobility—but we’ve lost the clarity on virtue itself. The culture of technocratic primacy rewards singularity: total, often maniacal, dedication to one domain at the expense of the rest…. Singular focus is not a human trait. It is a machine trait. Human life is fragmented on purpose. We are meant to be many things: friend, worker, parent, neighbor, mentor, pupil, citizen.

3. “The Vanishing of Youth” by Victor Kumar, published in Aeon.

Population decline means fewer and fewer young people, which will lead to not just economic decay but also cultural stagnation and moral regress.

Sometimes I’m asked (for example, by my wife) why I don’t want a third child. ‘What kind of pronatalist are you?’ My family is the most meaningful part of my life, my children the only real consolation for my own mortality. But other things are meaningful too. I want time to write, travel and connect with my wife and with friends. Perhaps I’d want a third child, or even a fourth, if I’d found my partner and settled into a permanent job in my mid-20s instead of my mid-30s… Raising children has become enormously expensive – not just in money, but also in time, career opportunities and personal freedom.

4. “Three tragedies that shape human life in age of AI and their antidotes”, by brothers Manh-Tung Ho & Manh-Toan Ho, published in the journal AI & Society.

In this paper, we [the authors] discuss some problems arising in the AI age, and then, drawing from both Western and Eastern philosophical traditions to sketch out some antidotes. Even though this was published in a scientific journal, we published in a specific section called Curmudgeon Corner. According to the journal it "is a short opinionated letter to the editor on trends in technology, arts, science and society, commenting emphatically on issues of concern to the research community and wider society, with no more than 3 references and 2 co-authors.”

The tragedy of the commons is the problem of inner group conflicts driven by the lack of cooperation (and communication) when each individual purely follows his/her own best interest (e.g., raises more cattle to feed on the commons), doing so will undermine the collective good (e.g., the commons will be over-grazed). Thus, we define the AI-driven tragedy of the commons as short-term economic/psychological gains that drive the development, launch, and use of half-baked AI products and AI-generated contents that produce superficial information and knowledge, which ends up harming the individual and collective in the long term.

5. "Of Mice, Mechanisms, and Dementia" by Myka Estes.

Billions spent, decades lost: the cautionary tale of how Alzheimer’s research went all-in on a bad bet.

Another way to understand how groundbreaking these results were thought to be at the time is to simply follow the money. Within a year, Athena Neurosciences, where Games worked, was acquired by Elan Corp. for a staggering $638 million. In the press release announcing the merger, Elan proclaimed that the acquisition “provides the opportunity for us to capitalize on an important therapeutic niche, by combining Athena’s leading Alzheimer’s disease research program with Elan’s established development expertise.” The PDAPP mouse had transformed from laboratory marvel to the cornerstone of a billion-dollar strategy.

But, let’s peer ahead to see how that turned out. By the time Elan became defunct in 2013, they had sponsored not one, not two, but four failed Alzheimer's disease therapeutics, all based on the amyloid cascade hypothesis, hemorrhaging $2 billion in the process. And they weren't alone. Pharmaceutical giants, small biotechs, and research organizations and foundations placed enormous bets on amyloid—bets that, time and again, failed to pay off.

6. “Schrödinger's Chatbot” by R.B. Griggs.

Is an LLM a subject, an object, or some strange new thing in between?

It would be easy to insist that LLMs are just objects, obviously. As an engineer I get it—it doesn’t matter how convincing the human affectations are, underneath the conversational interface is still nothing but data, algorithms, and matrix multiplication. Any projection of subject-hood is clearly just anthropomorphic nonsense. Stochastic parrots!

But even if I grant you that, can we admit that LLMs are perhaps the strangest object that has ever existed?

7. "A Prodigal Son" by Eva Shang.

My journey back to Christianity and why it required abandoning worship of the world.

How miserable is it to believe only in the hierarchy of men? It’s difficult to overstate the cruelty of the civilization that Christianity was born into: Roman historian Mary Beard describes how emperors would intentionally situate blind, crippled, or diseased poor people at the edges of their elaborate banquets to serve as a grotesque contrast to the wealth and health of the elite. The strong did what they willed and the weak suffered what they must. Gladiatorial games transformed public slaughter into entertainment. Disabled infants were left to die in trash heaps or on hillsides. You see why the message of Christ spread like wildfire. What a radical proposition it must have been to posit the fundamental equality of all people: that both the emperor and the cripple are made in the image of God.

8. “Why Cyberpunk Matters” by C.W. Howell.

Though the genre is sometimes thought dated, cyberpunk books, movies, and video games are still relevant. They form a last-ditch effort at humanism in the face of machine dominance.

So, what is it that keeps drawing us to this genre? It is more, I believe, than simply the distinct aesthetic…. It reflects, instead, a deep-seated and long-standing anxiety that modern people feel—that our humanity is at stake, that our souls are endangered, that we are being slowly turned into machines.

9. “You Are So Sensitive” by Trevy Thomas.

This piece is about the 25 percent of our population, myself the author included, who have a higher sensitivity to the world around us -- with both good and bad effects.

As a young girl, I could ride in a car with my father and sing along to every radio song shamelessly loud. He was impressed that I knew all the words even as the musician in him couldn’t help but critique the song itself. “Why does every song have the word ‘baby’ in it?” he’d ask. But then I got to a point where I’d leave a store or promise never to return to a restaurant because of the music I’d heard in it. Some song from that place would be so lodged in my brain that it would wake me in the middle of the night two weeks later…. about a quarter of the population—humans and animals alike—have this increased level of sensitivity. It can show up in various forms, including sensitivity to sound, light, smell, and stimulation.

10. “Solving Popper's Paradox of Tolerance Before Intolerance Ends Civilization” by Dakara.

A solution to preserving the free society without invoking the conflict of Popper's Paradox.

… Are we now witnessing the end of tolerant societies? Is this the inevitable result that eventually unfolds once an intolerant ideology enters the contest for ideas and the rights of citizens?…

Have we already reached the point where the opposing ideologies are using force against the free society? They censor speech, intervene in the employment of those they oppose, and will utilize physical violence for intimidation.

11. “Knowledge 4.0” by Davi.

From gossip to machine learning - how we bypassed understanding.

Speech allowed us to transmit knowledge among humans, the written word enabled us to broadcast it across generations, and software removed the cost of accessing that knowledge, while turbocharging our ability of composing any piece of knowledge we created with the existing humanity-level pool. What we call now machine learning came to remove one of the few remaining costs in our quest of conquering the world: creating knowledge. It is not that workers will lose their jobs in the near future, this is the revolution that will make obsolete much of our intellectual activity for understanding the world. We will be able to craft planes without ever understanding why birds can fly.

12. “Problematic Badass Female Tropes” by Jenn Zuko.

An overview of the PBFT series of 7 that covers the bait-and-switch of women characters that are supposed to be strong, but end up subservient or weak instead.

The problem that becomes apparent here (as I’m sure you’ve noticed even in only this first folktale example), is that in today’s literature and entertainment, these strong, independent women characters we read about in old stories like Donkeyskin and clever Catherine are all too often subverted, altered, and weakened; either in subtle ways or obvious ways, especially by current pop culture and Hollywood.

13. "The West is Bored to Death" by Stuart Whatley, published in The New Statesman.

An essay on the classical "problem of leisure," and how a society/culture that fails to cultivate a leisure ethic ends up in trouble.

Developing a healthy relationship with free time does not come naturally; it requires a leisure ethic, and like Aristotelian virtue, this probably needs to be cultivated from a young age. Only through deep, sustained habituation does one begin to distinguish between art and entertainment, lower and higher pleasures, titillation and the sublime.

14. “MAGA As The Liberal Shadow” by Carlos.

In a very real sense, liberalism is the root cause of MAGA, and it's very important to understand this to see a way forward.

It’s no wonder that I feel liberalism as the source of this eternal no: it is liberals who define the collective values of our culture, as it is the cities that produce culture, and the cities are liberal. So the voice of the collective in my head, is a liberal. My little liberal thought cop, living in my head.

4chan is great because you get to see what happens when someone evicts the liberal cop, the shadow run rampant. Sure, all sorts of very naughty emotions get expressed, and it is quite a toxic place, but it’s like a great sigh, finally, you can unwind, and say whatever the fuck you want, without having to take anyone else’s feelings into account.

15. “The Blowtorch Theory: A New Model for Structure Formation in the Universe” by Julian Gough.

The James Webb Space Telescope has opened up a striking and unexpected possibility: that the dense, compact, early universe universe wasn't shaped slowly and passively by gravity alone, but was instead shaped rapidly and actively by sustained, supermassive black hole jets, which carved out the cosmic voids, shaped the filaments, and generated the magnetic fields we see all around us today.

An evolved universe, therefore, constructs itself according to an internal, evolved set of rules baked deep into its matter, just as a baby, or a sprouting acorn, does.

The development of our specific universe, therefore, since its birth in the Big Bang, mirrors the development of an organism; both are complex evolved systems, where (to quote the splendid Viscount Ilya Romanovich Prigogine), the energy that moves through the system organises the system.

But universes have an interesting reproductive advantage over, say, animals.

16. “Tea” by Joshua Skaggs.

Joshua Skaggs, a single foster dad, has a 3 a.m. chat with one of his kids.

My second night as a foster dad I wake in the middle of the night to the sound of footsteps. I throw on a t-shirt and find him pacing the living room, a teenager in basketball shorts and a baggy t-shirt….

“I broke into your closet,” he says.

“Oh yeah?” I say….

“I looked at all your stuff,” he says. “I thought about drinking your whiskey, but then I thought, ‘Nah. Josh has been good to me.’ So I just closed the door.”

I’m not sure what to say. I eventually land on: “That’s good. I’m glad you didn’t take anything.”

“It was really easy to break into,” he says. “It only took me, like, three seconds.”

“Wow. That’s fast.”

“I’m really good at breaking into places.”

17. “Notes in Aid of a Grammar of Assent” by Amanuel Sahilu.

Through the twin lenses of literature and science, I take a scanning look at the human tendency to detect and discern personhood.

This is all to say, a main reason for modern skepticism toward serious personification is that we think it’s shoddy theorizing….

But I think few moderns reject serious personification on such rational grounds. It may be just as likely we’re driven to ironic personification after adjusting to the serious form as children, when we’re first learning about language and the world. Then as we got older the grown-ups did a kind of bait-and-switch, and serious personification wasn’t allowed anymore.

18. “Book Review: Griffiths on Electricity & Magnetism” by Tim Dingman.

In adulthood I have read many STEM textbooks cover-to-cover. These are textbooks that are supposed to be standards in their fields, yet most of them are not great reading. The median textbook is more like a reference manual with practice problems than a learning experience.

Given the existence and popularity of nonfiction prose on any number of topics, isn’t it odd that most textbooks are so far from good nonfiction? We have all the pieces, why can’t we put them together? Or are textbooks simply not meant to be read?

Certainly most students don’t read them that way. They skim the chapters for equations and images, mostly depend on class to teach the ideas, then break out the textbook for the problem set and use the textbook as reference material. You don't get the narrative that way.

Introduction to Electrodynamics by David Griffiths is the E&M textbook. We had it in my E&M class in college…. Griffiths is so readable that you can read it like a regular book, cover to cover.

19. “Fine Art Sculpture in the Age of Slop” by Sage MacGillivray.

Exploring analogue wisdom in a digital world: Lessons from a life in sculpture touching on brain lateralization, deindustrialization, Romanticism, AI, and more.

… As Michael Polanyi pointed out, it only takes a generation for some skills to be lost forever. We can’t rely on text to retain this knowledge. The concept of ‘stealing with your eyes’, which is common in East Asia, points to the importance of learning by watching a master at work. Text (and even verbal instruction) is flattening….

These days, such art studio ‘laboratories’ are hard to find. Not only is the environment around surviving studios more sterile and technocratic, but artists increasingly outsource their work to a new breed of big industry: the large art production house. A few sketches, a digital model, or perhaps a maquette — a small model of the intended work — are shared with these massive full-service shops that turn sculpture production from artistic venture into contract work. As the overhead cost of running a studio has increased over time, this big-shop model of outsourcing is often the only viable model for artists who want to produce work at scale….

And just like a big-box retailer can wipe out the local hardware store, the big shop model puts pressure on independent studios that train workers in an artisanal mode and allow the artist to evolve the artwork throughout the production process.

20. “Setting the Table for Evil” by Reflecting History.

About the role that ideology played in the rise and subsequent atrocities of Nazi Germany, and the historical debate between situationism and ideology in explaining evil throughout history.

Some modern “historians” have sought to uncouple Hitler’s ideology from his actions, instead seeking to paint his “diplomacy” and war making as geopolitical reactions to what the Allies were doing. But Hitler’s playbook from the beginning was to connect the ideas of racist nationalism and extreme militarism together, allowing each to justify the existence of the other. Nazi Germany’s war was more than just geopolitical strategic war-making chess, it was conquest and subjugation of racial enemies. The British leadership were “Jewish mental parasites,” the conquest of Poland was to “proceed with brutality!… the aim is the removal of the living forces...,” the invasion of the Soviet Union sought to eliminate “Jewish Bolsheviks,” the war with the United States was fought against President Roosevelt and his “Jewish-plutocratic clique.” Hitler applied his ideology to his conquest and subjugation of dozens of countries and peoples in Europe. He broke nearly every international agreement he ever made, and viewed treaties and diplomacy as pieces of paper to be shredded and stepped over on the way to power. Anyone paying attention to what Hitler said or did in 1923 or 1933 or 1943 had to reckon with the fact that Hitler’s ideology informed everything he did.

21. “Which came first, the neuron or the feeling?” by Kasra.

A reverie on the history and philosophy behind the mind-body problem.

… I do know that life gets richer when you contemplate that either one of these—the neuron and the feeling—could be the true underlying reality. That your feelings might not just be the deterministic shadow of chemicals bouncing around in your brain like billiard balls. That perhaps all self-organizing entities could have a consciousness of their own. That the universe as a whole might not be as dark and cold and empty as it seems when we look at the night sky. That underneath that darkness might be the faintest glimmer of light. Of sentience. A glimmer of light which turns back on itself, in the form of you, asking the question of whether the neuron comes first or the feeling.

22. “Dying to be Alive: Why it's so hard to live your unlived life and how you actually can” by Jan Schlösser.

Exploring the question of why we all act as if we were immortal, even though we all know on an intellectual level that we're going to die.

Becker states that humans are the only species who are aware of their mortality.

This awareness conflicts with our self-preservation instinct, which is a fundamental biological instinct. The idea that one day we will just not exist anymore fills us with terror – a terror that we have to manage somehow, lest we run around like headless chickens all day (hence ‘terror management’).

How do we manage that terror of death?

We do it in one of two ways:

Striving for literal or symbolic immortality

Suppressing our awareness of our mortality

23. “Thirst” by Vanessa Nicole.

Connecting Viktor Frankl’s idea of “the existence of thirst implies the existence of water,” to choosing to live with idealism and devotion.

This is, essentially, how I define being idealistic: a devotion to thirst and belief in the existence of water. To me, idealism isn’t about a hope for a polished utopia—it’s in believing that fulfillment can transform, from an abstract emptiness into the pleasantly refreshed taste in your mouth. (And anyway, there’s a whole universe between parched and utopia.)

24. “A god-sized hole” by Iuval Clejan.

A modern interpretation of Pascal's presumptuous phrase (about a god-sized hole).

People get to feel good about themselves by working hard at something that they get paid for. It also gives them social legitimacy. For some it offers a means of connection with other humans that is hard to achieve outside of work and church. For a few lucky ones it offers a way to express talent and passion. But for most it is an attempt to fill the tribe, family and village-sized holes of their souls.

25. “Have 'Quasi-Inverted Spectrum' Individuals Fallen into Our World, Unbeknownst to Us?” by Ning DY.

Drawing on inconsistencies in neuroimaging and a re-evaluation of first-person reports, this essay argues that synesthesia may not be a cross-activation of senses, but rather a fundamental, 'inverted spectrum-like' phenomenon where one sensory modality's qualia are entirely replaced by another's due to innate properties of the cortex.

I wonder, have we really found individuals similar to those in John Locke's 'inverted spectrum' thought experiment (though different from the original, as this is not a symmetrical swap but rather one modality replacing another)? Imagine if, from birth, our auditory qualia disappeared and were replaced by visual qualia, changing the experienced qualia just as in the original inverted spectrum experiment. How would we describe the world? Naturally, we would use visual elements to name auditory elements, starting from the very day we learned to speak. As for the concepts described by typical people, like pitch, timbre, and intensity, we would need to learn them carefully to cautiously map these concepts to the visual qualia we "hear." Perhaps synesthetes also find us strange, wondering why we give such vastly different names to two such similar experiences?

26. “Elementalia: Chapter I Fire” by Kanya Kanchana.

Drawing from the vast store of our collective imagination across mythology, philosophy, religion, literature, science, and art, this idiosyncratic, intertextual, element-bending essay explores the twined enchantments of fire and word.

My legs and feet are bare—no cloth, no metal, not even nail polish. Strangely, my first worry is that it feels disrespectful to step on life-giving fire. Then I see a mental image of a baby in his mother’s arms, wildly kicking about—but she’s smiling. I better do this before I think too much. I step on the coals. I feel a buzz go up my legs like invisible electric socks but it doesn’t burn. It doesn’t burn.

I don’t run; I walk. I feel calm. I feel good. When I get to the other side, I grin at my friends and turn right around. I walk again.

27. “When Scientists Reject the Mathematical Foundations of Science” by Josh Baker.

By directly observing emergent mechanical behaviors in muscle, I have discovered the basic statistical mechanics of emergence, which I describe in a series of posts on Substack.

Over the past several years, six of these manuscripts were back-to-back triaged by editors at PNAS. Other lower tier journals rejected them for reasons ranging from “it would overturn decades of work” and “it’s wishful thinking” to reasons unexplained. An editorial decision in the journal Entropy flipped from a provisional accept to reject followed by radio silence from the journal.

A Biophysical Journal advisory board rejected some of these manuscripts. In one case, an editor explained that a manuscript was rejected — not because the science was flawed but — because the reviewers they would choose would reject it with near certainty.

28. "The Tech is Terrific, The Culture is Cringe" by Jeff Geraghty.

A fighter test pilot and Air Force General answers a challenge put to him directly by Elon Musk.

On a cool but sunny day in May of 2016, in his SpaceX facility in Redmond, Washington, Elon Musk told me that he regretted putting so much technology into the Tesla Model X. His newest model was rolling out that year, and his personal involvement with the design and engineering was evident. If he had it to do over again, he said, he wouldn’t put so much advanced technology into a car….

Since that first ride, I’ve been watching the car drive for almost a year now, and I’m still impressed…

My daughter, however, wouldn’t be caught dead in it. She much prefers to ride the scratched up old Honda Odyssey minivan. She has an image to uphold, after all.

29. “The Lamps in our House: Reflections on Postcolonial Pedagogy” by Arudra Burra.

In this sceptical reflection on the idea of 'decolonizing' philosophy, I question the idea that we should think of the 'Western philosophical tradition' as in some sense the exclusive heritage of the modern West; I connect this with what I see as certain regrettable nativist impulses in Indian politics and political thought.

I teach philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology-Delhi. My teaching reflects my training, which is in the Western philosophical tradition: I teach PhD seminars on Plato and Rawls, while Bentham and Mill often figure in my undergraduate courses.

What does it mean to teach these canonical figures of the Western philosophical tradition to students in India?… Some of the leading lights of the Western canon have views which seem indefensible to us today: Aristotle, Hume, and Kant, for instance. Statues of figures whose views are objectionable in similar ways have, after all, been toppled across the world. Should we not at least take these philosophers off their pedestals? …

The Indian context generates its own pressures. A focus on the Western philosophical tradition, it is sometimes thought, risks obscuring or marginalising what is of value in the Indian philosophical tradition. Colonial attitudes and practices might give us good grounds for this worry; recall Macaulay’s famous lines, in his “Minute on Education” (1835), that “a single shelf of a good European library [is] worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.”

30. “What Happens When We Gamify Reading” by Mia Milne.

How reading challenges led me to prioritize reading more over reading deeply and how to best take advantage of gamification without getting swept away by the logic of the game.

The attention economy means that we’re surrounded by systems designed to suck up our focus to make profit for others. Part of the reason gamification has become so popular is to help people do the things they want to do rather than only do the things corporations want them to do.

31. “Pan-paranoia in the USA” by Eponynonymous.

A brief history of the "paranoid style" of American politics through a New Romantic lens.

As someone who once covered the tech industry, I join in Ross Barkan’s wondering what good these supposed marvels of modern technology—instantaneous communication, dopamine drips of screen-fed entertainment, mass connectivity—have really done for us. Are we really better off? ….

But we are also facing a vast and deepening suspicion of power in all forms. Those suspicions need not be (and rarely are) rationally obtained. The old methods of releasing societal pressures—colonialism, western expansionism, post-war consumerism—have atrophied or died. It should come as no surprise when violence manifests in their place.

Great list, thanks for sharing!

I reserved my Saturday morning to go through the list. So many great pieces! Particularly enjoyed the one about Cyberpunk, and I was also glad to read more of the author's writings about humanity and technology.