The Intrinsic Perspective's subscriber writing: Part 2

Sampling the state of the blogosphere (again)

Back in August I did a call for subscriber writing, promising to read each piece personally and then share the link and discuss it here. After receiving over 100 submissions, I broke the results into three parts. This is Part 2 (the final and third entry will come in a few weeks). In the initial Part 1 post, I discussed my thoughts from sampling so widely what could loosely be called “the blogosphere.”

After such an extensive survey, I am happy to report that the state of the blogosphere is excellent. Whenever you do an open call for other’s work, and certainly when you promise to read it all, there’s always the worry that most of what you receive is going to be, well, bad. Luckily, this wasn’t a problem. I was actually shocked by how good a lot of the pieces were, and how much I enjoyed them (one even inspired me to make a particular cocktail).

As I also said then, my goal here is not judgement or rating the work (nor does its inclusion mean I endorse any of the content), but rather reading and pulling out interesting excerpts to share.

These many pieces from the TIP community form a glimpse of what’s on the internet that would be hard to collate in some other fashion. It’s well worth perusing even if you didn’t submit anything, since you can find a bunch of gems, from how NASA selects for psychopathy to scientific theories of how civilizations collapse to how sourdough starter got people through the pandemic.

1. “American Astronaut” by Will Dowd, on how a touch of cold-blooded psychopathy can be a good thing (and how it made the NASA training process easier to get through). Take, for instance, the moon landing:

Careering over a landscape of jagged lunar boulders, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin came within just a few breaths of crashlanding. As Aldrin counted down the seconds until their fuel ran out, Armstrong was scanning for a patch of smooth Moon.

With less than ten seconds to go, he found it.

During this ordeal, both astronauts were wearing electrocardiogram sensors stuck to their shaved chests. In Houston, Mission Control was tracking—among other things—the astronauts’ heart rates.

Surprisingly, Armstrong’s heart rate never flickered during the treacherous landing.

Psychopathy? Perhaps the real reason was something else that happened years prior:

Armstrong showed no emotion at the funeral. He was back at work five days later. According to friends and colleagues, he never spoke about his daughter’s death.

Not once.

Maybe Armstrong’s heart rate was so low and imperturbable because his heart had already been so thoroughly broken.

2. “Great Artists Publish” by Charlie Rogers, which argues that people should share way more than they do:

Sharing your version one will build you an audience.

It might not be the hundreds of thousands you dreamed of when the idea first came to mind. It could be a fireside of a fanbase, an auditorium of an audience or a tidal wave of a tribe, the size doesn’t matter. Because being small is a secret superpower. It’s versatile. And you can do things that don’t scale. All you need to do is learn how to leverage it properly.

3. “On the (Gay) Fear of Holding Hands” by Daniel Sharp, a rumination on the why behind his unwillingness to hold hands with his boyfriend in public, and a resolution to overcome it.

Yes, I have since kissed men in public as well as private—at gay bars, that is, or at night, or when inebriated. But walking down the street in the cold light of day? No, no I don’t think I could easily do that even now. . .

However much I’ve changed, however happy I am with who I am now, that shame remains deep down and affects my actions (or inactions). It doesn’t require overt homophobia or abuse, either. I never faced much, if any, of that.

4. “About time” by Luis Mirón, which is a meditation on time (and a bunch of references from others).

The body stops. Growing, thinking, moving, feeling, experiencing sensation in the physicality of the body. When the body stops living, the mind stops thinking, the nose and mouth not breathing. The time that never really was existed only in the reachings of the mind, reminding the body of its, rather ironic, incessant movement, I would guess after even being dead. Odd is the use of the adjective, “dead.” Why does the adjective morph into a state of being, dead? Rather than a verb in the past tense, which seems more logical: She died. He’s dead connotes a present tense: Some-thing still exists, a corpse maybe?

5. “Simple Physics” by Kevin Leahy, a short story (very short, less than 700 words) which was published in Masters Review.

Here’s what I alone remember:

My mother’s coiled crouch, the mousetrap speed of her jump, the waffled lozenge pattern on the soles of her shoes. She leapt impossibly high, caught the balloon, and brought it back to me.

“Brendan,” Dad says, exasperation tempered with a gentleness he’d come into long after I was grown, “It was in her lungs by then.”

Now, Dad admits his back was turned. Danny was too young to remember, and Tim says he didn’t see. Maybe our mother, sick as she was, couldn’t have leapt the height of a man. But why, then, do I feel it happened—must have happened—could not have happened otherwise?

6. “Tedious night” is a poem by Péter Antal on his Substack.

A wonderer, to whom all desire

Every door she stepped

Trying, If trying is enough,

Asking, If asking if enough,

Nothing has ever changed

7. “The Slow Life of Pahokee: Why We Need Wilderness” by Katia Tarasava, PhD.

The elegant egrets, majestic herons, shy storks, nervous spoonbills, and gregarious cormorants seem to find enough food to coexist peacefully in their wide-open home. Only humans think that there is not enough space and resources for everyone, as they keep encroaching on the other animals’ territory.

Drain the swamp. Put in a highway — then another, faster one. Build a gas station to service the cars, and some businesses to bring in tourism. Straighten the river, funnel it into a reinforced canal, then control its flow through levies and dikes. Add in boardwalks, condos, boat ramps, quarries, and arable fields. Why do we have such a strong drive to change our environment? What about it is “not good enough” for us? What is it with this futile urge to build, pave over everything, and erect ugly square structures in places where organic natural shapes are meant to prevail?

8. “As The Stone Opens” by Magus Magnus, an author now on Substack.

Thus, The Stone Open. It’s ancient, the idea of one go, this core, geode, proof of concept, where’s crystallization, this is the life you’ve led. Your given. Society these days teaches fear of any loss of options: leaf through a catalogue of possibilities daily, as if that’s as it should be days on end, and then time slips and there’s no shape of the self, only a shadow of selections barely one’s own, smeared contours.

9. “Can AI Produce Great Art?” by Jason Rhys Parry, argues that:

The advent of AI is only the latest in a series of historical traumas that have slowly undermined our sense of human exceptionalism. While Darwin showed that we share an indivisible genetic link with other animals and evolved by employing the same mechanism of natural selection, our notable language and art capacities still set us apart. Now a crowded field of neural networks has usurped these aspects of our unique identity.

I think once the technology is more accessible the majority of the public will feel this directly.

10. “...it's a film in which not much happens” by Steven Reid:

What do we mean by slow cinema? Well, films in which the pace is certainly slow, meditative and may even lead to boredom, but there is more to it than that. Classics of slow cinema would include Antonioni’s Red Desert, The Sacrifice by Andrei Tarkovsky, and Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse. The Terrorizers and The Music Room are examples from this season, and both films prompted comments about the lack of action.

This definition of “slowness” means in terms of the plot, yes, but much more than that as well:

In the 1930s the average shot length for English language films was about 12 seconds; today it is 2.5.

11. “ChatGPT and the University’s Existential Crisis” by C.W. Howell is based on a viral tweet of his, wherein he asked his whole class to write essays using ChatGPT, and found numerous errors in all the assignments. He warns against using AI in education:

Implementing AI in this way would surely be fatal—for teachers and students. As Postman points out, education is fundamentally a communal endeavor. “You cannot have democratic…community life,” he writes, “unless people have learned how to participate in a disciplined way as part of a group. One might even say that schools have never essentially been about individualized learning.” An unthinking embrace of individualized technology that turns education into a solitary activity means the telos of education really would be Economic Utility. It is the logical end-point of seeing each human being as a rational consumer, a mechanical being whose atomic existence is oriented around each one’s individual preferences. Such intellectual and emotional siloing would invert John Donne’s famous line: now, every human is an island.

12. “Forecasting Authoritarian and Sovereign Power uses of Large Language Models” by K. Liam Smith asks what the Chinese Communist Party will do with AI, and makes an analogy to the last time propaganda was well-automated.

During the Nuremberg Trials, Hitler’s Minister for War production said:

Hitler's dictatorship differed in one fundamental point from all its predecessors in history. His was the first dictatorship in the present period of modern technical development, a dictatorship which made the complete use of all technical means for domination of its own country. Through technical devices like the radio and loudspeaker, 80 million people were deprived of independent thought.

13. “Life on the Grid” by Roger’s Bacon springboards from the finding that the geographic layout of our environment growing up impacts our cognition, especially navigation. But this piece is concerned more about metaphysical navigation, and in this way it’s really a manifesto.

To review: growing up in simplistic spatial environments and using GPS has given you brain damage and life has become a soul-crushing video game utterly devoid of mystery or adventure. We are trapped in the Grid like an insect in the spider’s web; vigorous struggle will only serve to entangle us further. To extricate ourselves, we must, as individuals, gently subvert the very foundations of the Grid, which is nothing external but a facet of human nature: the impulse towards control, the systematizing instinct, the part of us that abhors anomaly and ambiguity and seeks to eradicate them.

14. “The Structure of Love” by Jeffery Kursonis, ranges from love to physics.

When I began this journey in my youth I was a little nervous that I could actually discover anything new about love since hasn’t everything that could be said about love already been said? Well that’s what the thought experiment disproves. If we really understood love we would not have the world we have. Given the evidence of the sad state of our families and our societies it is clear there is more to be discovered.

15. “The bread sage who sent 1,600 sourdough starters around the world” is by Christian Näthler and is actually an interview with the bread sage herself—who during Covid shared her sourdough starter with, well, a lot of people.

LEXIE: This is hard because I think the point of bread, sourdough especially, is that it is so unremarkable. It's existed for as long as recorded history and yet there have been a small handful of non-cookbook books written about it in that whole time. The extraordinary qualities of it are found in its pure mundaneness, and the stories that came from a project that was intent on getting people to make it kind of reflect that. It's been a couple years now since the project was underway and what has remained in my mind is the pure outpouring of gratitude and intimacy that came from the exchange. Just a bunch of strangers landing in my inbox telling me how little faith they had in the world and how this gesture restored it.

16. “Is Chess A Waste Of Time?” by Nate Solon, a Chess coach. My thoughts on reading this were that if asking “Is Chess a waste of time?” we are also asking, in many ways, “Is life a waste of time?” I think it would be too easy and inauthentic to answer a resounding no! to that question, for even the giants often feel their time is wasted. Consider Einstein:

Albert Einstein asked of the second world champion Emanuel Lasker, “How can such a talented man devote his life to something like chess?” . . .

Yet even Einstein, you could say, was rarely Einstein. He made most of the discoveries he’s famous for in a single year, when he was 26. He spent the second half of his life trying (unsuccessfully) to reconcile his theories with quantum mechanics. . . In a letter written shortly before his death, he confided to a friend, “The exaggerated esteem in which my lifework is held makes me very ill at ease. I feel compelled to think of myself as a swindler.”

17. “The Great Split” by Francisco Ferreira da Silva, a short story that starts with a quote from Thomas Nagel and is told by the small quiet impotent right hemisphere of a split-brain patient after treatment for epilepsy.

As we learned scrolling down the page, it is a well-documented fact that one of the post-split brains — typically the left one — will gain power over the other one and eventually take full control of the body. He made a point of reading this sentence out loud, not managing to keep a note of triumph from his voice. Did he even try, the sick fuck? We learn I'm doomed to a life of complete, heartless, inhumane isolation and he gloats? I saw red. I was livid. I raised our left hand, closed it into a fist and brought it down towards the table. I had no plan but to slam the anger away, and this was the only way I still could. Our hand stopped before hitting the wood. Against my will, our fingers slowly started moving, opening up and turning the mighty fist into a harmless open palm. He gently laid it down on the table and continued reading. I could feel the corners of our lips rising up into a mocking smile as he did so.

18. “Mapping out collapse research” by Florian Ulrich Jehn is a catalog of the academic approaches to “Why do civilizations collapse?” Florian reviews how these theories can be grouped into a handful of broad observations (assumptions?) like:

“Cultures rise through toughness and fall through their decadence”

“People will always try to consume all available resources”

“History is made of recurring patterns and we can measure them”

“Societies get ever more complex, but at some point complexity cannot be supported”

My main takeaway is that this field still has a long way to go. This is troubling, because in our society today we can see signs that could be interpreted as indications of a nearing collapse. There are voices warning that our global society has become decadent (writers like Ross Douthat), that we are pushing against environmental limits (for example, Extinction Rebellion), that we are having a decreasing return of investment for our energy system (for example, work by David Murphy) and that there has been an overproduction of elites in the last decades (writers like Noah Smith). This means we have warning signs that fit all major viewpoints on collapse.

19. “The Struggle to Be Interesting is Real” by James F. Richardson on expressive individualism, which he says grew into the mainstream and is really about social demarcation.

I’ve always been amazed at how the 50 and under set really throw themselves into these lifestyle consumption worlds. The sheer monotony of their professional lives strikes me as an undeniable motive to somehow appear interesting to their work colleagues.

“Did you know Sarah and her husband are ballroom dancers?”

“Jack is an ultra-marathoner. He runs 45 miles to the office each day. Can you believe it?”

And on and on.

20. “32 Minutes and 29 and a half years” by Kate Waldwick, which is nominally about turning 30 during a pandemic, but it’s really about how we approach, and find, the meaning in life—and if that’s at an individual level at all.

I used to think if I just worked hard enough, I would get to where I needed to go. I would cross some finish line of “Congrats you did it! You found your life’s purpose and now you’re fulfilling it!”

29 ½ is not old, but it’s old enough to know that finish line doesn’t exist. It’s a plot device reserved for airport novels and sponsored posts from instagram gurus.

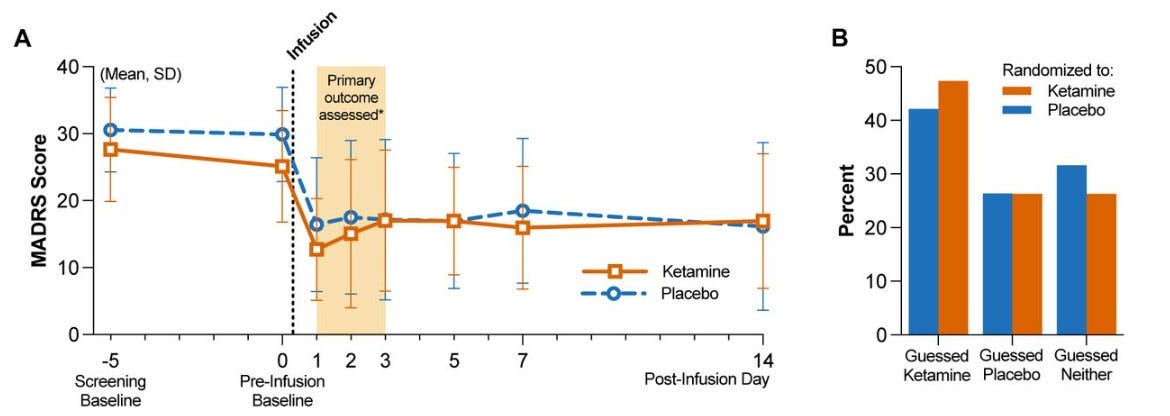

21. “Is ketamine as good as placebo or as good as ECT?” by Awais Aftab is a deep-dive into the effectiveness of ketamine as a treatment for depression.

What does this all mean? What are we to make of this?

One possibility is that the skeptics have been correct all along, and ketamine’s rapid antidepressant effects are nothing but expectancy effects and “placebo.” This possibility remains in play, but it is not the only possibility.

22. “How I made depression work for me” by Tom Kealy is about the actual personal experience of depression (amidst the pandemic). Apparently there’s a lot stronger stuff than ketamine.

The worst part wasn't the loneliness: it was the ward had an effective treatment. You see, they keep the good stuff, the pills that actually work, behind lock and key. These aren't your run of the mill SSRIs. No, they're more potent than that. They're your opiates and your barbiturates, and your lithiums and your benzos. They're the drugs which really sort out your head. You’re given them and it’s like clouds have broken in the curdled sky of your emotions. The thing they show you is that it's all in your head, everything you think about yourself, other people, even the world. It's all made up. And whatever you're doing, you're doing it to yourself.

23. “Boxes” by Richard is a short little reflection about moving, and boxes, and the boxes we put ourselves in.

From the age of 18, I’ve moved four times. That’s an average of 6 years per place. I am terrible at moving. I start with a brilliant plan, then the move day shows up, and I’m never ready. The whole thing collapses into an overwhelming blur. Every. Single. Time.

24. “Why Scientists Don’t Debate” by S Peter Davis is about the recent “debate me” controversy following Robert Kennedy’s appearance on the Joe Rogan show.

That brings us to Dr Peter Hotez, one of the most esteemed vaccine experts in the entire field, a man of several directorates with more chairs than a football stadium and winner of science awards they probably had to come up with just for him. He criticised Rogan for distributing medical misinformation, which led Rogan to drop the nice guy act and challenge Hotez to debate Kennedy on his show.

Hotez refused to take the offer . . . The problem is, Peter Hotez probably would lose a debate against Robert F Kennedy, Jr. For the same reason that Richard Feynman probably would lose a debate against a parrot. Public debate has almost nothing to do with discerning some kind of fundamental truth. It is, and always has been, primarily a form of entertainment.

25. “Design Is How It Works” by Jonah McIntire is about software, although it’s about more than that—it sees the developing abstraction of software as not some kind of mere mechanical evolution but rather a series of Kuhnian paradigm shifts in the design of how we manipulate software.

In practical terms, if you make an app about habit tracking (for example) the engineering is less about completing a cascade of necessary steps to code it so much as forming a novel and correct insight which would organize the resulting habit-tracking experience. Peter Naur chose to describe this process as theory building, and connects it back to philosophical notions such as Karl Popper’s world three and two realized objects.

26. “Mind-Body Problems” by Alaina Drake is on the personal experience of, well, not liking your body very much. Or, as is pointed out, perhaps that’s wrong—maybe the verbal “I” of Alaina just sides with the mind-side of the mind-body split, and shouldn’t.

My personal mind-body problem is basically this: I like my mind. I loathe my body. My body is the carrier of weight and responsibility, while my mind is full of freedom. My body is what it already is, while my mind can evolve and change itself. My body is where pain and discomfort are felt, and my mind would rather not deal with those things. My body needs so many things from me, and my mind resents it.

27. “Fame’s inflection point” by Natasha Joukovsky is about genius, but really it’s about what lies behind what we consider genius, which is the untouchable nature of fame, and the aura it brings to the work.

This brings me, finally, to the hypothesis I’ve been developing for a while, core to the new novel I’m working on, that our worship of godlike genius, our enduring commitment to its biographical fictions, our fascination with “the riddle of the artist” itself—it’s all in service not of some general, indiscriminate desire for status, power, fame, and fortune, but a very specific one: to pass the threshold that I’m going to call fame’s inflection point. This being the point at which the value of a person’s art in the absolute broadest sense—everything they make, say, do, capture, etc.—no longer primarily derives its power from what, but who. Not from the artifact, but the artist.

And, as Natasha points out, the end state of this is a kind of snake-eating-tail recursion, where people are famous for merely being famous. Or in other words, an influencer.

28. “About Time” by Luis Miron is note, a meditation, on time.

Everyone believes in time; but cultures differ on its direction, and whether time actually, forever flows forward. I don’t believe in this version of time since for Emily Dickinson, it seems that time had stopped when she heard a fly buzz. Yes, maybe when she died did Dickinson feel that time stopped. But something tells me that Emily had heard a fly die before she died, the hum never ceasing.., time always stopping for her.

29. “Hyper Landscapes” by Taylor Foreman reminds me, in a way, of the concept of “hyper objects”—systems distributed in ways unimaginable to human minds. Taylor thinks of AI in a way like this:

The development of written language was like Prometheus bringing fire to humanity: it is powerful but caused a lot of collective pain. Mostly, this pain runs in the back of our minds like the hum of a forgotten box fan, only popping into our awareness in cases of addiction or existential dread.

We should understand AI (large language models) as the next great leap forward in human language, similar in scale to the world-shaking power the Hebrews stumbled upon.

30. “Artificial Persuasion” by Ted Wade, in which he overviews many of the dangers of AI, both aligned and unaligned (and how there can be little difference between the two). He ends with this stark message:

Harm could come in so many ways, but the general risk is often described as the erosion of our (civilizational) ability to influence the future.

31. “The Write Stuff” by Dante Langston is actually the first chapter of a novel, A Lie Never Dies, set in Portugal. A gun is introduced (hidden in a purse), and does go off, although not in the way intended.

Guns are not common in Portugal. They are highly regulated, and carrying one in your purse was probably illegal. . .

32. “Mrs Thatcher and The Good Life” by Graham Cunningham explores a hypothetical: what would Margret Thatcher have to say on our own times, particularly the woke vs. anti-woke debate.

This April is the tenth anniversary of the death of Margaret Thatcher. More than thirty years since she fell from power, her record as an interrupter and repulser of that progressive leviathan is unequalled in any major Western nation - a counter-revolutionary template. She was Ron DeSantis on steroids. Her Joan-of Arc-like unstoppableness - much more than any specific policy successes - is the real reason why she became so enduringly internationally famous.

33. “The unbearable lightness of overcommunication” by Nikola Stikov, who considers options for why people are so slow to email back, like maybe:

We are all live action roll-playing (LARPing) and the constant back-and-forth is just the byproduct that is supposed to convince us that we are being productive.

. . . I keep wondering how people functioned before the internet. Meetings still happened, didn’t they? So why do I now have to create a fucking Doodle poll every time I need to get three people on the same call?

34. “Should we still send links to friends?” by Charlotte Dune asks why it is that we send memes to our friends, arguing the act is really about sharing how we experience this crazy online world.

While we know deep down that everyone has access to everything, our instinct is to still send content to friends because these transmissions are a language, a way of speaking. Meme speak, so to speak, a way to communicate our affection and ideas, to share the qualia of the Internet, and a very easy way indeed. Each content-only message is like a quick heart emoji to say, I’m thinking of you. Please like me back. Please love me. Please click my link. Please watch this. Please validate me with your time and attention. Please laugh simultaneously with me from afar.

35. “Like a Thousand Suns” by Varun Ravichandran is about grandparents aging, and dying—or perhaps, as Varun argues, not really dying at all.

She is 89, and her body was starting to severely weaken too. The last time we went to Mumbai to meet her, just 6 months back, she would sit with us and talk for hours at a stretch - chuckling at jokes (her face lighting up as she laughs), sharing stories, admonishing us for being lax on following some of our rituals. On that last visit she explained many things to me about Sri Vaishnavism, the tradition Charanya belongs to. There is so much knowledge, so much lived wisdom, locked up inside our grandparents. They carry it around without a fuss, sharing only if we care to ask. She was in high spirits during that last visit.

36. “How to be an unsuccessful thinker” by Kasra on the many many pitfalls of intellectual investigation.

People like Paul Graham have pointed out that when it comes to intellectually challenging work, you can only expect a few productive hours per day before quality deteriorates (in his case, five hours). June Huh, the Fields medalist who dropped out of high school, does about three hours of focused work per day. People have varying degrees of stamina, so you can experiment: start with two hours, and if you can hit that consistently, bump it up. Just remember that it's very easy to convince yourself you're still being productive when you've actually spent the past half hour alternating between (A) staring at the same sentence with furrowed eyebrows, and (B) binge-scrolling Twitter every few minutes.

37. “Can I Tell You a Story About How the Cruel Oppression of a Dictatorial Regime Changed My Life For the Better?” by Corey Jackson is about how small moments of viewership can spark great change.

I was in no danger of being arrested, executed or my house being bulldozed in the middle of the night (though the house was torn down soon after we moved out). . . .

The woman on my TV had none of these securities and was in the grip of a loss the likes of which I will never experience. So how could I be as distraught as she was? It didn’t make any sense - her anguish was justified. What reason did I have to feel the same way she did?

38. “Travel with children, Part 1” by Mark Hannam is satirical fiction wherein quantum physics professors act like spoiled children and graduate students shepherd them around. Or maybe it’s actually realism, come to think of it.

Five minutes later we were in the ice cream parlour that's decorated in bright 1950s colours. My supervisor's face was covered in ice cream, and so was his shirt front and sleeves, and probably his trousers, too. But I hadn't seen him so happy since his last paper was accepted.

“How about we wipe your hands,” I said, “And then you can sign this travel form?”

“Mmm mmm mmm,” he agreed, through a mouthful of ice cream.

39. “ChatGPT will change human communication” by Kevin Whitaker predicts that the rise of AI will make us more specific in our instructions and communication; in other words, we will begin to talk to humans more like LLMs. “Think step by step. . .”

. . . there's no denying that new technologies can change how humans communicate. One example from McCulloch: when all communication was face-to-face, it was customary to address others with a formal greeting, but this wasn't possible over the telephone: how can you address someone when you don't know who's calling? Thus "hello" entered the lexicon, first only for phone calls, but eventually as an acceptable in-person greeting too.

40. “Barbie (2023) REVIEW: We're ALL Barbie!💖” by Celeste Briefs is exactly what it sounds like, but one of the things that sets it apart is that the author emphasizes the humanistic message of the movie:

Barbie is a film about what happens when a doll, which for decades has been caught in the crosshairs of the war between feminism and the patriarchy, being accused of being a capitalist tool of the patriarchy to oppress women and lauded as a representation of everything women can do and be, learns that this is the experience of every living woman and, in many ways, every living human in the real world.

41. “Six Minutes” by Wolemercy, a prose poem about the end of the world.

I don't want to change the world. I want to be at my nephew's graduation and surprise Father with a visit on his birthday. I want to read the great books my friends write and tell them they suck at football when they miscue a goal kick. I want to star-gaze sober as I tell the girl at checkout I write her letters in the afternoons. The world may die but I want to live, and this is the way, dear friend.

42. “My Moments: An antisocial media experiment” by Gilad Seckler is about Twitter withdrawal—or “X” withdrawal, I suppose—and valiant attempts to take the worst away from the social media platform.

These days, it’s hardly a novel observation that the bloom is off the rose of social media. Substack continues to beef with Elon Musk over Notes; major media outlets declare Twitter dead and speculate about the “new new reading” environment; Montana is banning TikTok. For me, though, this pet project started earlier—or maybe bubbled up concurrently—when I decided for purely personal reasons that I was dissatisfied with my Twitter use: It had once again become a vapid, reflexive thing I did at the slightest sign of boredom or discomfort.

43. “Biased Towards Survival” by Nick Beem is about a psychological effect called “negativity bias” wherein humans are more affected by negative experiences than positive ones.

The dynamics of evolution provides a ready explanation for this tendency: avoiding threats is far more important to survival than pursuing opportunities. Missing a chance to eat is not fatal, but missing signs of an approaching predator could end your chance to contribute to the gene pool.

44. “Mindwar & Psy-Ops” by M.J. Hines is about how close creativity industries (like writing) are to traditional military “psy-ops”—and their actual effectiveness.

More recently, the CIA briefed a toy designer from Hasbro responsible for GI Joe to prototype frightening action figures of a devilish-looking Osama Bin Laden in an effort to make Pakistani children afraid of him.

45. “The Responsibility of the Victim” by The Delinquent Academic is about the personal experience of being epileptic, and regularly experiencing terrifying seizures that change your very self.

I’m 30 now. And have had many seizures. In many odd places. It’s usually in the morning, right after waking. I’ll be doing something, talking, brushing my teeth, naked in the shower, whatever, and then I’ll stop, stare into the distance, as if I’m no longer conscious, or am suddenly controlled by another entity. Then I shake, viciously, smashing everything nearby. The possession doesn’t end there. Afterward I’m demonic. Aggressive. Strange. Lacking motor coordination. I will fight close friends or my brothers if they happen to be there. I’ll run down roads if I’m by myself. If I’m in public, I’ll say and do odd things. I never remember anything. Usually, after about ten-fifteen minutes, I’ll slowly come to, like I tried to describe above. When I do, I experience impossible dread. Impossible in the sense that for several minutes I believe I am going to die.

Looking forward to some weekend reading.

Very excited to dig into all of these (and finish up going through some of the links from the last installment) but the thing that springs immediately to my mind while glancing over the blurbs is in relation to the invocation of language and the myth of Prometheus in the Hyper Landscapes excerpt: I had a similar thought when I first encountered the tale "The Smith and the Devil"," which by some accounts is possibly the oldest surviving western story, dating back to the Proto-Indo-European era. It seemed almost immediately to me that the story— about the Devil granting the Smith the ability to bind any substance to any other substance, whereupon the Smith promptly binds the Devil to a chair, preventing him from ever collecting his debt— had to be about the development of language and possibly even the sense of our inner selves that language allows us to explore in our thoughts. Then again I may be biased because I'm a writer with an interest in the nature of consciousness.