The unbearable whiteness of Neptune

Science's fiery hunt for real colors

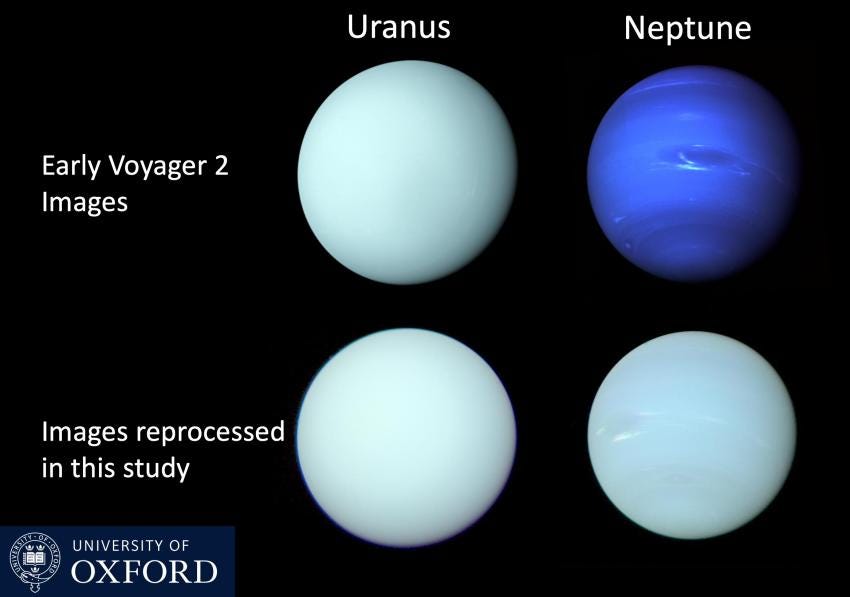

Neptune, it turns out, isn’t actually blue. A few months ago, scientists bid us say farewell to its cerulean skies, say goodbye to its signature hues on glossy pages and in movies. We were fooled from when Voyager 2 slingshotted past the planet in the 1980s; the resultant widely-publicized color photographs were actually composites, put together in a way it’s not a stretch to call propaganda.

Here’s the real Neptune—a milky orb nude and sickly, a blind eye. The planet now looks just as unmemorable as Uranus (which, by the way, has lost most of its supposed green as well). No, instead of Superman blue Neptune is an interstellar cataract.

Even in languages like Chinese, Neptune’s name translates as something like “sea king star,” and yet clearly this planet is not Neptune, god of fertility and bounty, strapping with his mane, his masculine human chassis, his vitality—only a hint of color remains, bleeding away.

There’s a paint color, Neptune Blue, that will need to be renamed. Every children’s book with a little toy model of the solar system will need to be de-hued. Plenty of sci-fi movies have lost their carefully-chosen chromatic setting; the finale of Ad Astra will need to be reshot, the background of Event Horizon made less colorful.

No doubt, Neptune’s loss of color may seem a strange subject for an essay. Perhaps completely inconsequential. But in Neptune’s loss of color I see the long march of science, and its effect on our even longer search for meaning.

People, after all, did not take the news well. Here’s some of what was said in reaction:

“Nothing ruins my childhood more than finding out Neptune isn't dark blue.”

“I refuse. They will not take any more beauty from the universe. They have already taken too much.”

“I don’t care, Neptune will always be blue for me.”

“Fucking sucks that Neptune isn't that nice dark blue color but super pale blue instead.”

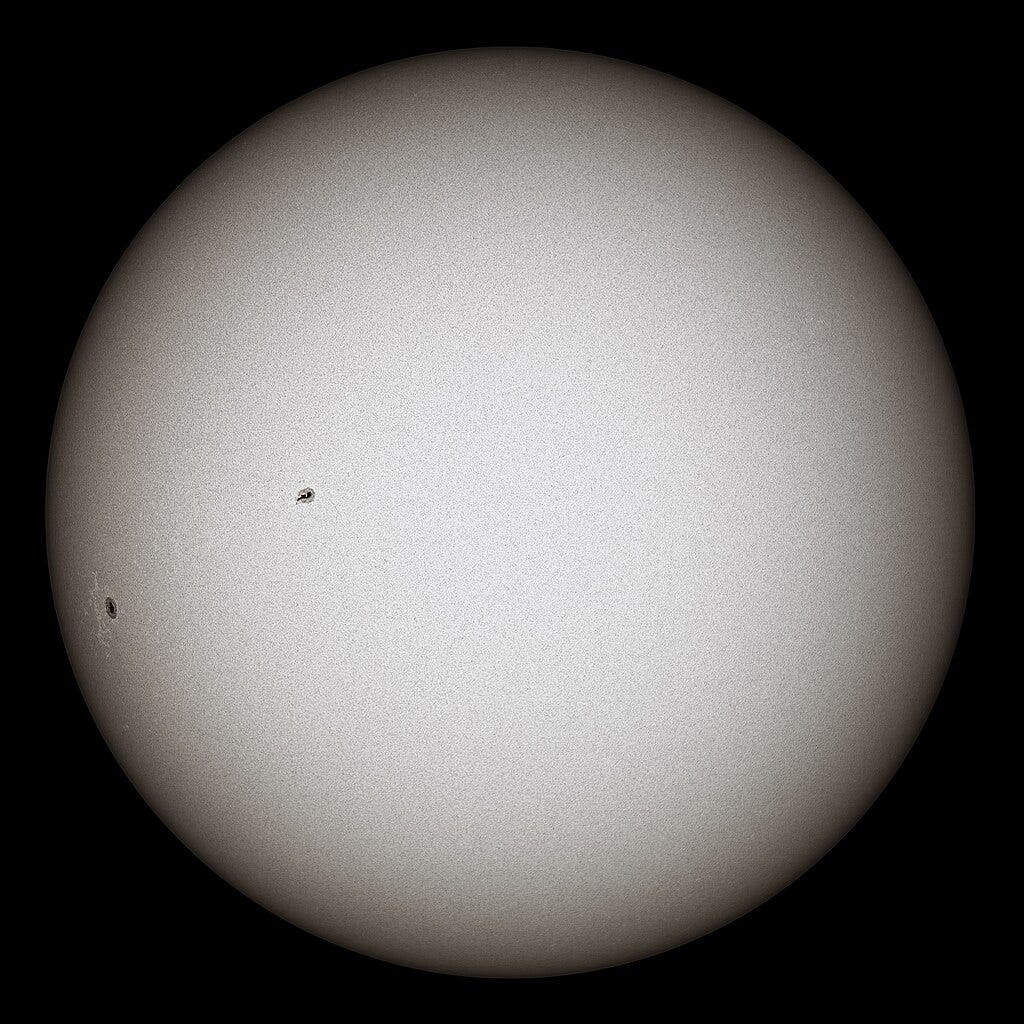

And so on. It’s unpleasant for us to notice the universe is basically just white spheres, rotating. Did you think your sun a beautiful orange? No, it is the white of all colors, so therefore has no colors at all, a sphere voided. Behold your sickly sun.

The reaction to Neptune’s new nudity reminded me of one of the most famous chapters in Moby-Dick (like many chapters, more of an essay than fiction) titled “The Whiteness of the Whale.” Nothing is more terrible, Melville argues, than the whiteness of absence, for it reveals the uncomfortable truth about ontology.

… in essence whiteness is not so much a color as the visible absence of color; and at the same time the concrete of all colors; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows—a colorless, all-color of atheism from which we shrink?

And when we consider that other theory of the natural philosophers, that all other earthly hues—every stately or lovely emblazoning sweet tinges of sunset skies and woods; yea, and the gilded velvets of butterflies, and the butterfly cheeks of young girls; all these are but subtile deceits, not actually inherent in substances, but only laid on from without; so that all deified Nature absolutely paints like the harlot, whose allurements cover nothing but the charnel-house within; and when we proceed further, and consider that the mystical cosmetic which produces every one of her hues, the great principle of light, forever remains white or colorless in itself, and if operating without medium upon matter, would touch all objects, even tulips and roses, with its own blank tinge…

And of all these things the Albino whale was the symbol.

Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?

This chapter is when Captain Ahab’s struggle against Moby Dick, supposedly for personal revenge over his leg (sawed off in the jaws of the monster), instead becomes something more. The white whale represents by its mere existence the greatest of cosmic horrors—pure absence, complete disregard for human wants or needs. A situation Ahab finds intolerable. The whiteness of the whale is an unbearable reminder that the rest of nature has been “painted like a harlot” and offers only the illusion of meaning. The colors are just in our heads. And so is everything else.

The blank page. White! When creatures live underground, eyeless, slinking, what color do they become? Think of Sméagol: colored, tan, happy by the river bank. Think of Gollum. White! Anglerfish who have never seen the sun, evolving without vision into endless forms most ugly. White! Cosmic maggots wiggling in the dark between stars. White!

All of this is, of course, considered inappropriate to remark upon for scientists. It is seen as giving away too much to merely acknowledge that maybe, just maybe, the progressive march of science has some sort of impact on humanity’s search for meaning, and isn’t simply universally positive and affirming.

Philosopher Daniel Dennett had a term for this: the idea of a “universal acid,” a hypothetical substance that can eat through any container, will burrow and burrow to the core of the world. Dennett used universal acid as a metaphor for Darwinism, but, in the maximally pessimistic take, he may as well have been talking about all of science: a universal acid that threatens to strip away meaning. Even if we don’t go that far, what’s definitely true is that science is a universal de-coloring agent. It is achromatizing. For Neptune’s loss of color has played out again and again as science has advanced and the natural world has been stripped of its subjective paint. This aspect of science is by design; it removes subjectivity on purpose, a strategy that goes back to science’s origins. In 1623, when Galileo Galilei wrote his scientific manifesto, The Assayer, he declared that:

Philosophy is written in this grand book, the universe, which stands continually open to our gaze. But the book cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language the read the letters in which it is composed. It is written in the language of mathematics…

Emphasizing mathematics explicitly meant emphasizing the quantitative aspects of matter: all of nature, Galileo argued, should be understood in terms of properties like size, shape, location, and motion. And ever since, science has worked to push all qualities back, including color, yes, but far more as well. As Hume wrote in A Treatise of Human Nature:

Vice and virtue, therefore, may be compared to sounds, colors, heat and cold, which, according to modern philosophy, are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind.

The end result is that, according to science, there are no qualitative properties anywhere in the universe—no blues and no reds, no pleasures nor pains, no vices nor virtues, nothing at all… except those that exist inside our skull. As contemporary philosophy of mind Philip Goff imagines in his book Galileo’s Error:

If Galileo traveled in time to the present day to hear that we are having a difficulty giving a physical explanation of consciousness, he would most likely respond, “Of course you are; I designed physical science to deal with quantities not qualities.”

But science’s old and very purposeful compartmentalization, a strategy that has been wildly successful, must necessarily break down. Its unstable structure is why neuroscience is in such a strange spot, since neuroscientists are forced, usually against their will, to deal with the undeniable fact that we are conscious beings experiencing, and those experiences have qualities. While the rest of the sciences can content themselves with the colorless, those on the hunt for a scientific theory of consciousness must actually look for real colors.

For hundreds of years, science’s progression has meant that every atom has become as white as Melville’s whale, as white as Neptune. Imagine the colors draining from the great map of the cosmos, retreating like a tide going out, paints losing themselves into pale, until the whole world is white. Except… there! Right there! A small bloom of color still pulsing. Irreducible iridescences of purples and reds and greens. The human brain as an unbowed bloom of hues that stubbornly refuses to go away, even as everything around it fades to white. And that’s the way it sits now, barely holding on.

But this small bloom of color is dense with qualities, for that’s where all the colors in the universe have gone. They’ve all been compressed and pushed back into a little three-pound lump of matter. Its density makes it unstable. Maybe one day it will sputter out altogether and only whiteness will remain, even inside our heads. It will turn out we are under a cruel illusion, and humans as entities will join the ranks of Neptunes and suns, nothing but another colorless shape. Or maybe not. Maybe one day that small irreducible flicker will become a flame, and then there will be a roar of expansion as every color under the rainbow begins to spill across the frame of the world once more, out and out, until the whole universe is technicolored with magic once again.

Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?

This is a swell article, but I think it the takeaway should be that Neptune sucks as a planetary body and is terrible and we should grind it into a fine powder and give Uranus rings or something worthwhile. It's stupidly far away, it's old, it's slow, and it doesn't even have the cool weird spinny-ness of Uranus. Besides, it's lost it's fancy blue color so now we're stuck with a discount Uranus floating around the edge of our lil star going "HEY I'M STILL COOL DON'T FORGET ABOUT ME" while we all know that Neptune would be forgotten in the grand annals of history if it evaporated from this fine reality one cheery summer morn.

What a great piece! I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what is lost when only the countable matters. You illustrate the effect of science very clearly.

Another domain is culture. When we only value the easiest metrics to obtain then the ultimate benchmark, money, becomes the most important factor. It bums me out.