We Are Not Low Creatures

Life on Mars aims us all upward

We are not low creatures.

This is what I have been thinking this week. Even though humanity often does, at its worst, act as low creatures.

Some act like vultures, cackling over the dead. Or snakes, who strike to kill without warning, then slither away. Or spiders, who wait up high for victims, patient and hooded and with the blackest of eyes.

But as a whole, I still believe that we are not low creatures. We must not be low creatures. We simply need something to help us remember.

An arrow-shaped rock on Mars, only a few feet across, and found sitting at the bottom of an ancient dried-up river, helped me remember. For, on Wednesday, and therefore lost amid the news this week, a paper was published in Nature. It was the discovery that—arguably for the first time in history—there are serious indications of past life on Mars.

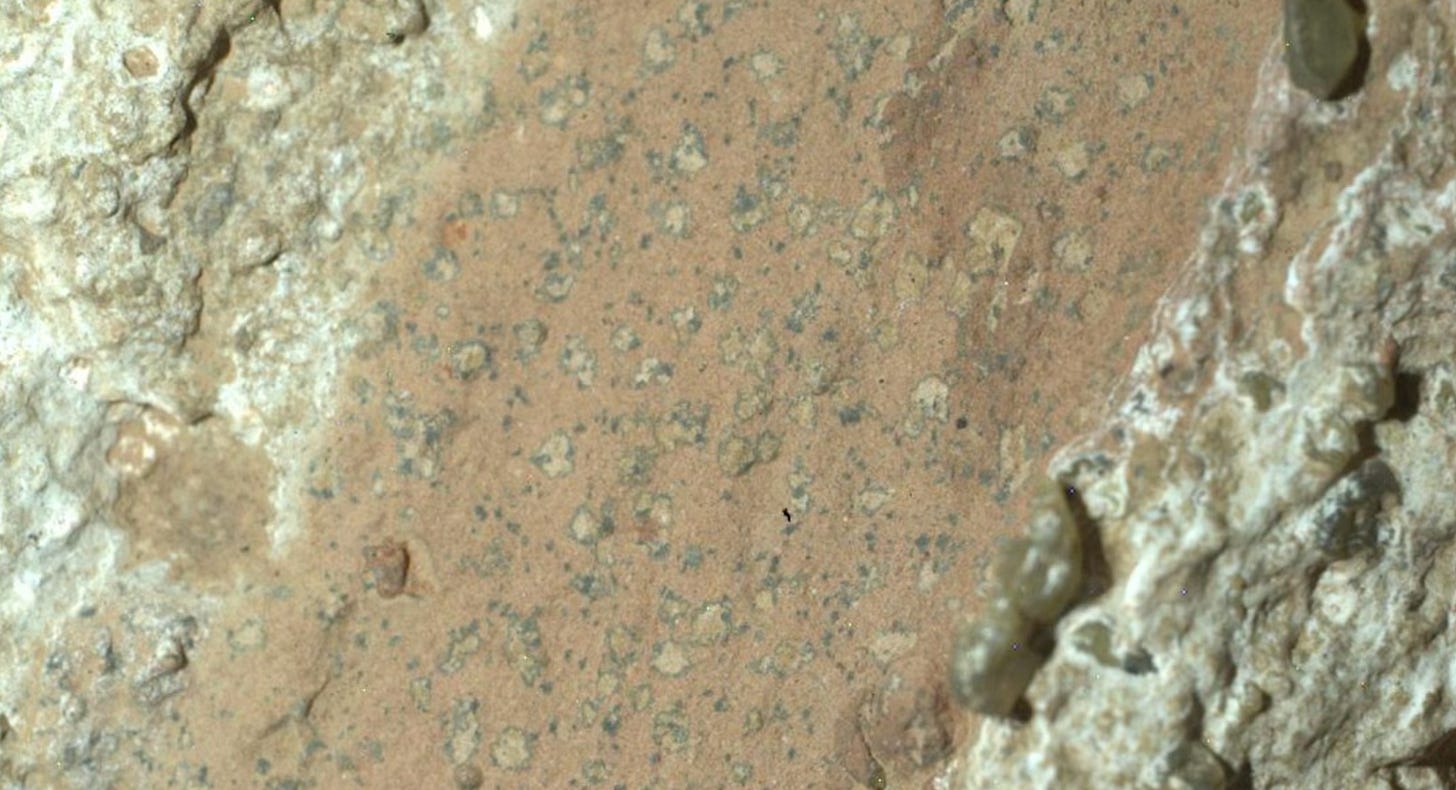

Specifically, these “leopard spots” were analyzed by the rover Perseverance.

According to the paper, these spots fit well with mineral leftovers of long-dead microbes.

Minerals like these, produced by Fe- and S-based metabolisms [iron and sulfur metabolisms], provide some of the earliest chemical evidence for life on Earth, and are thought to represent potential biosignatures in the search for life on Mars. The fact that the reaction fronts observed in the Cheyava Falls target are defined by small, spot-shaped, bleached zones in an overall Fe-oxide-bearing, red-coloured rock invites comparison to terrestrial ‘reduction halos’ in modern marine sediments and ‘reduction spots’, which are concentrically zoned features found in rocks of Precambrian and younger age on Earth.

It matches with what we know about some of the oldest metabolic pathways here on Earth, and there are not many abiotic (non-biological) ways to create these sorts of patterns, and of those abiotic ways (the null hypothesis) there is no evidence right now that this rock experienced those.

Maybe this helps people contextualize it: If this exact same evidence had been found on Earth, the conclusion would be straightforwardly biological, and an abiotic explanation would be taken less seriously—such a finding would likely end up in textbooks about signs of early life on Earth and used to argue for hypotheses about how life evolved here. Remember, without fossils, all we have are similar traces of the early life on Earth. What are cautiously called “biosignatures” on Mars are the exact same kind of evidence we accept about our own pre-fossil past (in fact, this is arguably better evidence than what we have on Earth if you compare like-to-like cases and factor in the instrument differences and limitations).

Unlike other recent, and far more controversial claims of alien life (e.g., statistically debatable signs of potential biosignatures on extrasolar planets light years away, or Avi Loeb’s ever-changing hub-hub around an extrasolar comet) the scientists in this case have been very conservative and careful in their language, as well as their scientific process.

Of course, there could still be a mistake in the data processing or analysis (although again, this has been in the works for over a year, and overseen by many parties, including NASA, the editors of Nature, and the scientists who peer reviewed the paper). It’s true that the minerals and patterns might have come from some sort of extreme heat that occurred in the ancient lakebed. But an alternative abiotic process that explains the growth-like patterns of leftover traces would have to have occurred all throughout the rock, not just in one layer, like it would from an errant lava flow, and that’d be quite strange.

Regardless, scientifically, signs of life on Mars are absolutely no longer a fringe theory. It is no longer “just a possibility,” and it is definitely not “unlikely.” There is at least a “good chance,” or another glass-is-at-least-half-full equivalent judgement, that one of the planets closest to us once also had life.

And in this, now, I think the path is set. The light is green. The time for boots on the ground is now. Don’t send a robot to do a human’s job; the technology is too constrained. There are signs of past life on Mars, and so to be sure, we must go. We must go to Mars because humanity cannot be low creatures. We must go because a part of us belongs in the heavens. So we must go to the heavens, and there find answers to the ultimate questions of our existence.

Our origins will be revealed on Barsoom.

I don’t think most understand what it means if Mars turns out to have once had life. It is not just the discovery that alien organisms existed back then. It’s much more than that. One of the most determining facts in all of history may become that Mars is a dead planet.

Now, that alone is not news. Even as a child I knew Mars was a dead world, because that’s how the red planet is portrayed culturally, like in The Martian Tales, authored by Edgar Rice Burroughs (writer of the original Tarzan). Those novels sucked me in as a preteen with their verbosity, old-world elegance, romance, and copious amounts of ultra-violence. The New York Times once described the Martian Tales as a “Quaint Martian Odyssey,” perhaps because the pulpy book covers had a tendency to look like this:

But in all the adventures of the Earth man John Carter, teleported to Mars by mysterious forces, and his love the honorable Princess Dejah Thoris of Helium, and his ferocious-but-cuddly alien warhound, Woola, the actual main character of the series was Mars itself. A dying world, a planet dusty with millennia, known as “Barsoom” by its inhabitants, Mars had once been lush with life, but by the time the books take place its remains form a brutalist landscape, dominated by ancient feats of geo-engineering like the planet-spanning canals bringing in the scant water, and the creaking mechanical “atmosphere plants” that create the thin breathable air.

The dying world of Barsoom captured not just my imagination, but the imagination of kids everywhere. Including Carl Sagan. In his Cosmos episode about Mars, “Blues for a Red Planet,” Sagan says that when he was young he would stand out at night with arms raised, imploring the red planet to mysteriously take him in, as it had John Carter.

Mars being a dead world, just as Burroughs imagined the background environs of Barsoom to be (but without the inhabitants of big green men), matters a great deal. Because if Mars once harbored life, the record of that life would remain, unblemished and untouched, in far better condition than here. Making Mars basically a planetary museum for the origins of life, preserved in time.

For example, Mars has no plate tectonics, which continually rebury our Earth, making discovering anything about early life on our blue world nigh impossible. Here, not only has the entire ground been recycled over and over, but every inch of Earth has been crawled over by other living creatures for billions of years, like footsteps upon footsteps until there is nothing left but mud. This contamination is absent on Mars. And so all the chemical signatures that life left behind will have an orders-of-magnitude higher signal-to-noise ratio there, compared to here. Not only that, there’s ice on Mars. Untouched ice, undisturbed by anything but wind and dust, possibly for up to a billion years in some places. What do you think is in that ice? If this biosignature remains undisputed, and is not an error, then we should expect, very possibly, for there to be Martian microbes. Which might, and I am not kidding here, literally still be revivable. There have been reports of reviving bacteria here on Earth from 250 million years ago, which had been frozen in salt crystals (of which there are a bunch on Mars in the form of ancient salt deposits, and they’d again be much better preserved than here).

Mars is therefore like a crime scene that has been taped off for billions of years, containing all the evidence about the origin of life and the greater Precambrian period. Fossils could be on Mars from these times. Even assuming that Mars never developed multicellular life, there could be fossils of colonies, like chains and algae and biofilms. There are fossils of such things on Earth that are 3.5 billion years old, like stromatolites (layers of dead bacteria). Yes, you can see something that was alive 3.5 billion years ago with your naked eye. You can hold it in your hand. And that’s on our churning, wild, verdant, overgrown, trampled, used-up and crowded blue world, not the mummified red one next door.

The Nature paper (without really mentioning it explicitly) supports the thesis that Mars is a museum for the origin of life. The rocks don’t show any scorching or obscuring from acidity or high temperatures. There’s basically no variation in the crystallinity to mess up the patterns here. Everything just looks great for making the inference that this was life’s leftovers.

Overall, a biosignature like the one published this week switches Mars from “A nearby dead world that we could go to if we felt like it” (all while nay-sayers shout “Why not live in Antartica lol!”) to an absolute requirement for a complete scientific worldview. If you care at all about the origins of life itself, then you want us to go to Mars. Mars could solve questions like:

How did life evolve? Under what conditions? How rare are those conditions? Did life spread from Earth to Mars? Or Mars to Earth? Or did they both develop it simultaneously?

I can’t help but note: the reactions would indicate an iron-sulfur based metabolism for the Martian microbes, which is a metabolism that goes back as far as Earth’s history does. There is literally something called the “iron-sulfur world hypothesis.” So there’s a very close match to what was just found on Mars, and the potential early metabolic pathways of Earth. This could be a case of convergent evolution, which tells us a lot about the probabilities of life evolving in general. Or it could indicate transfer between planets via asteroid collisions knocking chunks off into space, which sounds crazy, but was a surprisingly common event. Early life could have hitched a ride on such a chunk (also called “natural panspermia”). Natural panspermia could either be an Earth → Mars scenario, or a Mars → Earth scenario.

Intriguing for the Mars-as-a-museum hypothesis, it seems a priori more likely to be Mars → Earth scenario for any potential panspermia, as Mars was a bit ahead, planetary formation wise. If this ended up being true it would mean Mars contains the actual origins of life. And so any signs of life’s origin literally aren’t here, on Earth, they are over there (explaining why we are still stuck on this question).

Finally, one must mention: it could have been artificial panspermia. Seeding. A fly-by. You just hit a solar system and start delivering probes containing a bunch of hardy organisms that love iron and sulfur. Two planets close by at once? And they’re both wet with water? That’s an incredibly tempting bargain someone may have taken, 4 billion years ago. There’s zero, zip, nada evidence for it, right now. It’s just another hypothesis on the table, one that the museum of Mars could rule in or out. Consider that a co-author of the study said that, if the biosignature was made by life, its results:

… means two different planets hosted microbes getting their energy through the same means at about the same time in the distant past.

Anyway, enough handwaving speculation, the point is that we now have an entire planet that can potentially answer the Biggest Questions, and we won’t know those answers until we legitimately go and check. As Science writes:

Bright Angel samples and others are stored on the rover and at cache points on the Martian surface in labeled tubes for eventual retrieval, but the proposals for how to go get them are in a state of expensive disarray.

I think it’s really important we solve that “expensive disarray.” And not just retrieve these particular samples mechanically, as was planned in the usual Wile E. Coyote kind of NASA scheme involving launching the sample tubes into orbit to be caught by some other robot.

When it comes to space, we’ve completely forgotten about humans, and how capable we are, and the vital energy that comes from humans doing something collectively together. Maybe because we didn’t have a good uniting reason. Now we do. One human on Mars could do more in a single day with a rock and a high school level lab than robotic missions could do in decades.

Humanity is fractured and warring. We kill each other in horrible ways. Our mental health? Not great! Our democratic values? Hanging by a thread!

I know it sounds crazy, but in a way I think it’d be better to go to Mars than have yet another political debate. Yes, much of our troubles are policy—there’s a ton of true disagreements, poor reasoning, and outright malice. But think of the nation as if it were just one person. For an individual, it’s true that digging deep down into a personal issue and reaching some internal reconciliation after a bunch of debate is sometimes the answer. But other times, you’ve just obsessed over the problem and made it larger and worse. Then, it’s actually better to just go out into the world and embrace the fact that you’re a human being with free will who can Just Do Things. Same too, I think, with civilizations. We can Just Do Things too. And going to Mars, done collectively, nationwide, in the name of humanity as a whole, would have deeply felt ramifications for the memes and ids and roiling hindbrains that dominate our culture today.

And yes, getting to Mars is not going to be easy. NASA needs to get off its collective butt and actually operate in a way it hasn’t in decades and switch to caring about human missions. Our tech titans will need to refocus away from winning the race about who can generate the most realistic images of cats driving cars, or whatever.

But most of all, we need to remember that we are not low creatures.

Let’s go to Mars.

Astrophysicist here. I've always found it striking that back in the 1970s, the first Viking lander on Mars carried a suite of life-detection experiments, one of which got a positive result consistent with microbial metabolism (the labeled release experiment). This was dismissed after the same lander's Gas Chromatograph–Mass Spectrometer (GCMS) found no organic material. But, in 2008, further experiments showed that the GCMS could feasibly have destroyed any organic compounds, leading to a false negative.

Gilbert Levin, the PI of the labeled release experiment, maintained his whole life that his experiment did find evidence for life on Mars.

I'm amazed that in the half-century since Viking, these results have never really been followed up. The community seemed to conclude that there was no evidence for life on Mars and stopped trying. It's only in the last decade, with our new ability to detect bio-signatures on nearby exoplanets, and with the hint of phosphene on Venus (etc) that the idea has started to seem less crazy.

With these new findings, I wouldn't be surprised if it turns out that Levin was right all along. Exciting times! But as you say, we need a serious sample return or crewed mission to get to the bottom of it.

Anything to propel us into Expanse world ASAP