What killed the writer Mark Baumer?

The publishing industry's troubled relationship with writers

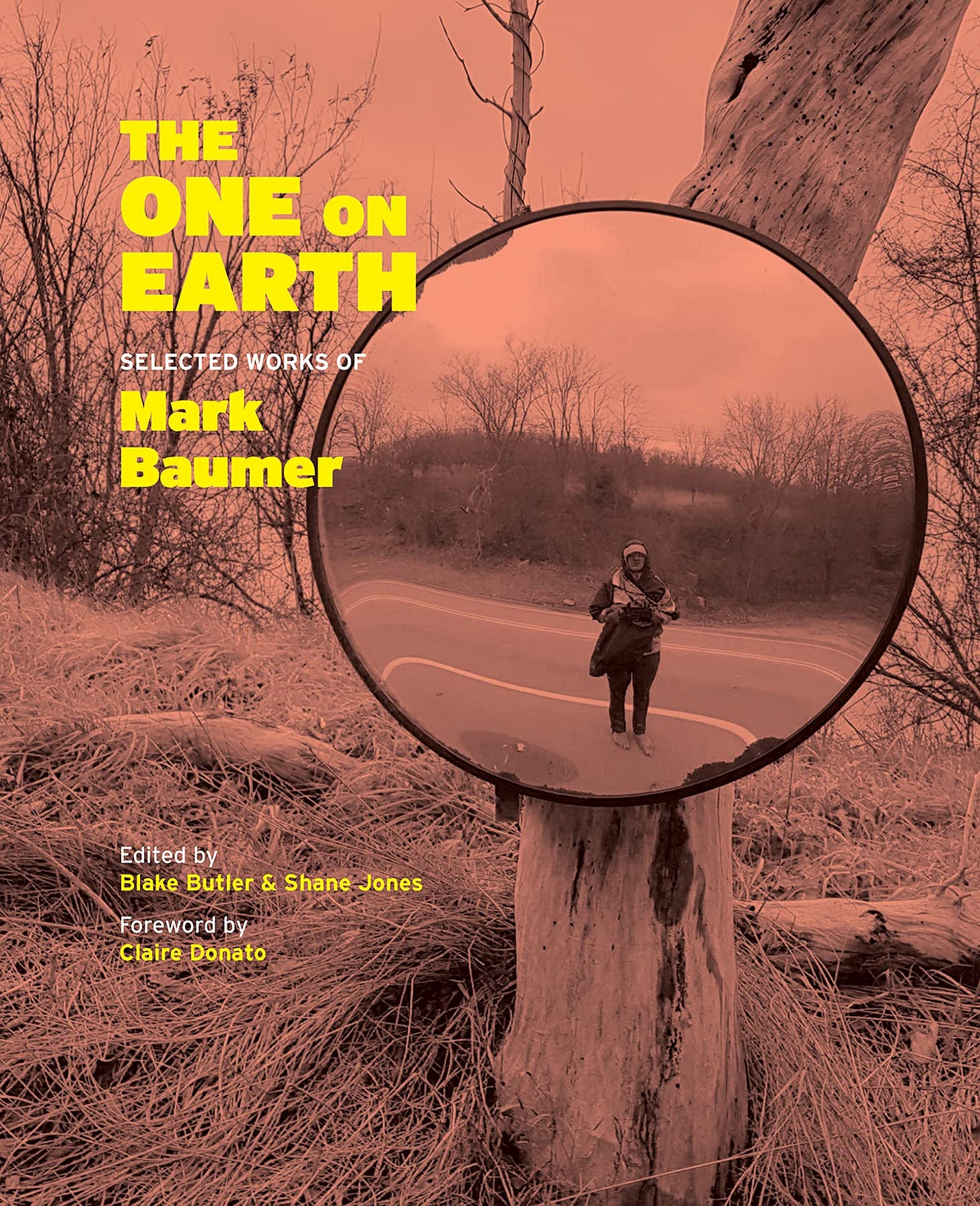

You likely haven’t heard of him. He was not famous, and only 33 at the age of his death. Merely an aspiring writer and devoted environmentalist. Though the automobile crash that took his life back in 2017 did make a few headlines due to its extremely unusual circumstances. It was a notable event for me personally, since I had been following his relatively obscure blog. At the time the tragedy seemed to me emblematic of something significant just out of sight, an obscured thing it has taken me years to even glimpse through a glass darkly.

What’s so interesting about this one man’s death? Let’s start with the fact he was a young writer who once taught a class at Brown University called “Everything is Fiction,” and was later struck dead by a gas-guzzling carbon-monoxide spewing beast of an SUV while he was walking on the side of the highway during the 101st day of his attempt to cross America barefoot, an effort to raise money online to combat climate change, and all this, his death, the accident, occurred on the day Donald Trump took the office of the president in 2017. The collision itself happened just hours after Marc had posted a photo to his blog, the ominous www.notgoingtomakeit.com, of his bare feet next to yellow graffiti letters that read “KILLED” with an arrow pointing forward to his immediate future.

His death was reported in The New York Times, although the ironies, the layer of facts so darkly comic it was tragic, the extremely American nature of it all, were only hinted at.

This is because the headlines at the time of his death naturally focused on the easy story of Mark Baumer’s death: his goal to walk across America barefoot to raise awareness and money for climate change. The same story is reflected in the documentary Barefoot: the Baumer Story came out in 2019. In the documentary, his girlfriend at the time described his motivation to go on the walk, which he would never complete, as “He sort of felt a kind of sense of urgency about changing his life in some way.”

It’s not made explicit in the coverage or the documentary, but at first glance he seemed similar to Christopher McCandless from Into the Wild, another saintly young man dispossessed of the modern world who would eventually meet a tragic end.

There wasn’t much mention of his writing by the press. Which makes sense, since it wasn’t well known. At the time Baumer was mainly a self-published writer of experimental poems and novellas, although he had won a few awards for his poetry in literary magazines. He also had professional success locally at Brown University, where he taught a fiction class known for being weird and, paradoxically, for being without criticism.

“Mark takes a different tact than most professors,” said Kelsey Shimamoto ’13, who took Baumer’s class last fall. She said students wrote profusely and explored new literature styles through reading assignments like Urs Alleman’s “Babyfucker,” but that the class never used the conventional method of collectively critiquing students’ work. “We had almost no criticism for the entire course.”

His gentleness comes across clearly through his videos in his attention to animals and inanimate objects. At the same time, there is an element of violence in the footage he took during his walk, like he is trying to force the worst of America onto himself, as if he could take it into his body and purge it. He wrote dark prose on his blog in those last few days, the ones just before his death and as Trump’s arrive to the White House edged closer:

Remove your tongue. Burn it in a tiny aluminum can fire. Sew the crispy tongue back inside your mouth. Staple every piece of garbage you create to your forehead as a reminder you’re alive in this historical moment of death.

or

I’m ashamed of the majority of white men of america to the point I want to remove all evidence of being a white male from my body.

The footage he took during his barefoot walk, of which is quite a lot, contains a level of mania and fatalism that comes across even before Trump won the election in November. Because it is a crazy thing to do to walk barefoot across America. Your feet swell up to enormous sizes, they become scorched by pavement.

Baumer had read the book Born to Run, about how humans had evolved to run barefoot over long distances. It convinced him he would be safe shoeless. I too once read Born to Run, and started running barefoot down the hills and grasses and through the streets of my sleepy college town, just like our ancient ancestors. I fucked up my knee and never fully recovered.

Yet none of this, the environmentalism, the bare feet, was how I knew him, and it’s what makes me feel the real story is more complicated, darker, perhaps more like Baumer’s own prose. And please note: I didn’t know him personally. But before his death I was aware of him in that online way. There was a sense at the time he was traveling on a path parallel to me. Not the path of activism, but of literature and publication.

See, I had been looking for a literary agent. And when you do that, you start researching them, like finding old YouTube videos to see what they like and their tastes. And these strange YouTube videos kept popping up whenever I typed in a big-name agent into YouTube, a series called “I called an agent because I am an unpublished author and I need a massive book deal.” It contained titles like “Mark Baumer calls Susan Golomb ,” or “Mark Baumer calls Claudia Ballard.” No one ever picked up his calls, because literary agencies don’t, as a rule, answer their phones. He’d call, and then, in an odd voice not quite his own, riff into the answering machine. Sometimes he’d be in his room, sometimes at a busy intersection, sometimes in an aisle at Staples. The calls are like weird pieces of performance art. He’d start with: “ SUUUUUSSSSSSSAAAAANNNNN!!!!” and eventually get to rambles like “Jonathan Franzen does words better than anyone!” (editorial disclosure: Susan Golomb, who is Jonathan Franzen’s agent, along with many others, is also my agent). He’d often end with a litany of his own failures, like mentioning that “none of [my videos] have gone viral, they’ve literally gotten one or two views.”

To be honest these videos contain a level of aggression are hard to dismiss entirely as performance art or quirkiness. But me touting some amateur outside diagnosis would, I think, be a too-easy dismissal of what Mark was doing, which was trying to reconcile himself to the publishing industry, processing it through the kind of online performativity that he’d come to make so much use of in other arenas. At the time I found many of the videos jarring but also quite funny, because it’s easy to demonize gatekeepers when you feel, as all unpublished authors do, that you are being ignored. Looking back at those phone calls now, published yes, but also years older, what I think is: you know, that agent probably double-checked the windows were locked that night.

The driving desire of a book deal crops up all the time in Mark’s output and blog. But he couldn’t get one. Instead, in an experiment, he self-published 50 books on Amazon in a year. These short books, which are mostly quirky poetry and prose, are almost a parody of the publishing industry, like he’s saying “If I can publish fifty books then what is publication anyways?” The titles are things like A Weather Balloon on Saturn: A book about a weather balloon on Saturn and The Day I Died And Left America: A book about the day I died and left america.

One saw clearly his honest desire for publication when there was a rare drop in the performance mask. For example, when Mark Baumer responded in an interview to why he didn’t give up his barefoot quest to walk across America, he answers seriously that:

Deep down I still hold out hope I can convince someone to give me a book deal for this. I don’t know if I’m supposed to think that way or be honest about it but I’ve kind of thought this way my whole life. I keep doing things imagining they will lead to book deals and then I don’t ever get book deals.

According to his father, Mark “wanted to be famous.” For if the writer Tao Lin could be famous, also an author of quirky short books with strange titles like Eeeee Eee Eeee: A Novel, and whose persona has the same awkward and lilting tint of performance art, why not Mark Baumer?

It’s easy to mistake a “hippie” demeanor for being easy-going, but Mark was competitive (all artists are). He played hockey in high school, then played baseball in college and his team made it to the Division III finals. He liked the hardcore encouragement of the Navy SEAL Youtuber David Goggins. I mean could you walk 1,000 miles barefoot, with your feet fucked up with tar and blisters, without being an extremely competitive person? Even if it’s just with yourself?

All this is just to say that Mark didn’t remind me of Chris Mccandless going to find himself in Alaska, ethereally non-materialist, verging on Christ-like. No, even before the accident, who Baumer reminded me of, in his own strange way, was Gatsby.1 Because when you’re not in the publishing industry, you’re out across the harbor in West Egg, looking at that green light bobbing across the waves. If only I were in East Egg. . .

Of course, maybe this was the lens I understood Mark through because I was looking out at the water in the same way. There’s a whole host of people standing there on those docks, waiting to be published, and occasionally, just occasionally, one transcends, uplifted into The Green. People are standing there now. And it’s easy for those inside the industry to forget that longing, that feeling of impossibility, and the unfairness of it all.

Most literary agents receives dozens, if not literally hundreds, of queries every single day. Of which they take on something like 0.0001% of everything that’s sent. Writers must pitch hundreds of personalized query emails to get, at best, a handful or a dozen requests for full manuscripts, most of which are, in turn, never responded to. And agents face the same difficulties! For they must in turn submit to an editor, hoping to hear back. And that editor is in turn behold to some senior editor, and so on, forever really—there’s not any individual to actually blame in this process. It’s just kind of the system we have.

Yet if you ever publicly complain about the arbitrariness of the pipeline as a whole that leads from undiscovered manuscript to published novel, be aware that your fellow discourser is probably contemplating a variant of William F. Buckley’s quip about why Robert Kennedy never appeared on the debate show, Firing Line: “Why does bologna fear the grinder?”

That’s the easy rejoinder: maybe your work just sucks. Your bologna fears the grinder. Your prose doesn’t have that magic publishable quality. It’s an easy answer because it’s protective. The system works. Like Leibniz’s/Panglosses’ idea that this is the best of all possible worlds (or Ayn Rand’s defense of capitalism), it’s a seductive belief because it switches is to ought. You are published, therefore you ought to be published.

As a published novelist now at least somewhat immunized from the response, let me say: the publishing process is brutally unfair. So many brilliant writers either almost failed, or did fail. Some killed themselves. Probably way more than we know. Of course there are the famous cases like John Kennedy Toole, who ran a garden hose from his car exhaust after just a handful of rejections of his manuscript A Confederacy of Dunces. When it was posthumously published due to his mother’s efforts, it won the Pulitzer Prize. For a more contemporary example, consider Hellen DeWitt, a brilliantly intellectual heavy-hitter of a writer, who at some point called her agent threatening to commit suicide over some editorial rejection. Or consider Dow Mossman, who was put in a mental asylum after the publication of The Stones of Summer, which only sold 3,000 copies when it first came out in 1972 (although it was reissued in 2000, since the book has some of the most explosively lyrical prose ever written). Mossman worked odd jobs for the rest of his life and never published again. I could go on, dragging out literature’s dirty laundry, but I think the point is made and everyone can come up with their own examples, both great and small.

I’m not saying Mark Baumer had some genius manuscript hidden away like Toole. Mark’s writing strikes me sometimes shockingly good, but also uneven, sometimes over-the-top—but that’s not my point. It just seems to me that the literary world breaks people sometimes. Psychologically. And not because they are driven insane by their beautiful minds, but because they are ignored, or feel they are ignored. And more often than not the people the industry breaks are not the elites with their Ivy League degree who come to NYC to intern for The Paris Review after their parent’s helping checks clear. No, it breaks the outsiders who want in on the bright lights and no one told them the publishing industry, like almost everything in life, is all about who you know. When Mark got into Brown University, his father incredulously told him “Baumers don’t go to Brown.”

It’s hard to think of a contemporary writer who’s done the equivalent of working 12-hour days at a plastics factory, like Mark did. While the publishing industry has become much more diverse in many ways, its growing reliance on an elite MFA system to do the selective work for agents and editors has made it even less economically diverse than decades ago. I don’t have an MFA, and only got published because I literally moved to New York City, which by itself wasn’t enough, so I also had to get lucky with some literary awards. If I had stayed elsewhere, or moved but been unlucky with awards, I wouldn’t have been published. Of this I am sure. And I personally know a half-dozen writers who are unpublished but produce high quality material, better than many of those who are published. So I am convinced that the number of great unpublished authors in America may rival the number of great published ones. If this is true, and nothing I have seen of the pipeline has convinced me otherwise, this represents a failure—from top to bottom.

To be clear: I have no idea what to do about this. I have zero specific proposals for industry change, no new best practices. Neither do I actually have any unique insight into Mark’s personal motivations either. All I know is what everyone else knows. Mark had many sides. Like everyone’s true self, he cannot be located from the extrinsic perspective. All we end up with is a cipher that reflects back our own subjectivity. The environmental activism that led to his walk was real. So were all his political convictions. And the material cause of what actually killed Mark Baumer is known—the woman driver of the SUV was charged with straying out of her lane on a straight road. When she hit Mark his body flew 120 feet. Yet it somehow seems to me that what loomed behind him as he walked those dangerous highways, pushing him on with its invisible pressures, was a vast system of indifference that we never discuss. It’s a system that no individual can be blamed for, but that, collectively, maybe we all should be. And I’m not talking about climate change.

It’s worth ending on the ultimate irony. If someone were to pitch one last book deal in the form of a novelized version of Mark Baumer’s life, I suspect I know what the reply would be.

Too unrealistic.

Please consider donating to the Mark Baumer Sustainability Fund

The comparison to Gatsby holds moreso now. For both would be killed, in a way, by automobile accidents.

Thanks for your thoughtful essay on the shortcomings of the publishing process and the painful and frustrating process of seeking an audience and getting past the gatekeepers.

I’ve been writing for a living for most of my professional life. I’ve written columns, documentaries, novels (unpublished), scripts, screenplays, marketing copywriting and more. I’ve studied writing at school, in workshops, and attended conferences. It’s fair to say writing has been at the center of my life.

Something I recognized in your piece about Mark Baumer was a sense of desperation and expectation that I see in myself and that I’ve seen in other writers.

The intersection of art and commerce is well-known as a source of frustration for writers. That's where agents and publishers live. But what is less discussed is the intersection of craft and the desire to be recognized, or even celebrated, that can torment writers. When we entangle craft with the need to be seen, we do so at our peril.

As a writer, I have the usual frustrations that come with craft. I’m always trying to find better ways to get a character into a scene or make dialogue feel more authentic. From sentence work to rhythm and endless editing, I strive to make my writing shine. When I’m fully dedicated to that pursuit, I feel great. A day at my desk spent on storytelling is a good day indeed.

But then there’s the matter of how my work will be received. The matter of audience, money, accolades, the desire for recognition. Fantasies in the shower of speeches and notable mentions in the New Yorker and reviews in The New York Times. With every rejection I receive, there is a growing feeling of being left out of a conversation, and an endless, clawing need to be invited to the party, any party.

This insatiable desire is really not writing at all. In fact, it has nothing to do with writing. This is the fantasy of getting in and out of limousines. If there is any defense of this thirst for fame, it’s the hope that it would provide an environment where I can dwell for even longer in the life of my fiction, and be less distracted by the mundane problems of making a living. But that’s not really what drives it.

The more I feed the endless need to be recognized and praised for my work, the harder it becomes to write. The more desperate I feel about my life, scribbling away in obscurity with little or no external validation, the easier it is to fixate on agents and publishers as my only possible saviors. They are no longer people who sell products, they are the cure for what ails me. This state of helplessness is built on the premise that I’m miserable because nobody is reading my work, and that if I had literary success I would be happy. This is the fatal lie, I believe, that drives writers to early deaths.

I already know from my limited experience with success that I immediately want more success. And I also know from watching successful people that their recognition doesn’t seem to have provided them the relief I seek either. Graveyards are filled with famous artists who died miserable. Hemmingway, David Foster Wallace, the list goes on and on. It might feel like I’m just one big book deal away from feeling whole, but that’s not how happiness works. Does that stop me from daydreaming of success or wishing I would sell my work? No, not at all. But it does provide me with just enough self-awareness to know that my craving for success is my problem, not my lack of fame.

And the solution to that problem? For me, it’s to once again get back to writing. Because when I write something that I think succeeds as a piece of art, I feel a satisfaction and a serenity that nothing else can provide. Writing, for me, is and always will be, its own reward. It’s OK to want success, and it’s OK to feel the frustration that comes with rejection. That’s only human. But to confuse it with what it means for me to be a writer is to enter into a delusion that only deepens my desperation and diminishes my work.

So, in answer to your question, “What killed Mark Baumer?” I posit that his misconception that getting a book deal would kill a pain that comes from elsewhere is what killed him. I want things too, desperately, but shutting that voice out and getting back to work is all I’ve found that works.

Your deeply insightful piece made me think. Not merely of two or three, but many, truly many things about writing, writers, and the market. Above all and first of all, let me say this please. I feel very sorry for Mark Baumer. I drive often on the high roads (= highways), thus interstates, and, there, an autonomy of vehicles prevails. No place for men or women walking along for a longtime even in the very sideway. I hope his soul is in peace now and forever. The earth also has to stop warming itself up and up. Mark Baumer seems to me a sensible person in his essence.

Now, the market. Fist of all, my question to self and selves. Why do writers need readers? In the principle, sellers need buyers. The way of advertising and distributions matter too. There are pipelines on the market for products to flow. You rightly said of it as the industry, because it is the industry, in which duties and tasks are divided by professionals accordingly. If a writer-would-be wants to be properly acknowledged, he or she has to get into all of it in the industry, otherwise, let them stand at a street corner for readers-would-be to snatch up by.

Money matters, profoundly. Living is writing or vice versa. Otherwise, the existence of readers may not be crucial at the core. If I allow myself to state in oversimplification about visual artists, there are two types of desires. One is on the artists' life style, galleries, receptions, shows, parties, flashlights, magazine interviews, or, at least, possibility to say friends and relatives that "I'm artist". The other is creators who make arts and work in the same pace and ardency or naturalness of breathing air to live. The latter needs money to live, of course, but gallery receptions reside at no pivotal point.

I said of oversimplification. Well, actually, I suddenly realized I would be able to write on this topic (writers, readers, and the market) in my substack through an elaboration. I will, if that happens, mention this piece of yours about Mark Baumer's death. Thank you for your good writings as usual.