Billions in funding, and with recent glowing cover stories in Time Magazine, The New Yorker and The New York Times, it’s clear that the creed of effective altruism is on the rise. When I talk to its proponents it has the aura of being almost too successful, as they often mention secret internecine wars and squabbles only those on the inside care about. It’s certainly a movement I’m asked about all the time, especially lately. And when I am, what first springs to my mind is Bertrand Russell’s 1927 lecture titled “Why I am not a Christian,” for it’s a speech that summarizes my feelings about effective altruism. This may seem like an odd analogy, or even (to some) an insulting one, since the two are so different. But to see what I mean about it springing to mind, here’s a passage from Russell’s speech, but with “Christianity” replaced with “effective altruism:”

Some people mean no more by it than a person who attempts to live a good life. In that sense I suppose there would be effective altruists in all sects and creeds; but I do not think that that is the proper sense of the word, if only because it would imply that all the people who are not effective altruists—all the Buddhists, Confucians, Mohammedans, and so on—are not trying to live a good life. I do not mean by an effective altruist any person who tries to live decently according to his lights. I think that you must have a certain amount of definite belief before you have a right to call yourself an effective altruist.

In his lecture Russell handily gives short reasons why the traditional official reasons for believing in Christianity—like the arguments from first cause, from natural law, or from design—simply don’t hold water. Furthermore, Russell argues that Christianity, despite cloaking itself in moral certitude, actually leads to immoral outcomes when its beliefs are taken literally:

Supposing that in this world that we live in today an inexperienced girl is married to a syphilitic man, in that case the Catholic Church says: ‘This is an indissoluble sacrament. You must stay together for life.’ And no steps of any sort must be taken by that woman to prevent herself from giving birth to syphilitic children. That is what the Catholic Church says. I say that that is fiendish cruelty, and nobody whose natural sympathies have not been warped by dogma, or whose moral nature was not absolutely dead to all sense of suffering, could maintain that it is right and proper that that state of things should continue.

You can buy Russell’s criticisms of Christianity or not, things have certainly changed since Russell’s day in many ways, at least in some places, and while I myself am not a practicing Christian I lack his anti-Christian vitriol. But my point is just to make an analogy: that what Russell saw in Christianity, which he thought was based on bad philosophical reasoning and concomitant immoral outcomes, are things I see in effective altruism, which ultimately makes the philosophy unattractive to me. This is not because of some trite metaphor wherein “effective altruism is the new religion” or anything like that—it is because it is based on initially flawed reasoning that when taken literally leads to immoral outcomes.

Note that effective altruism, having grown up in academia, has a lot of jargon (not that there’s anything wrong with that, sometimes jargon is necessary). I’m purposefully not going to use much of it, with the goal of (a) non-experts being able to follow along, and (b) the criticisms I’ll discuss don’t ultimately need a technical presentation. For despite the seemingly simple definition of just maximizing the amount of good for the most people in the world, the origins of the effective altruist movement in utilitarianism means that as definitions get more specific it becomes clear that within lurks a poison, and the choice of all effective altruists is either to dilute that poison, and therefore dilute their philosophy, or swallow the poison whole.

This poison, which originates directly from utilitarianism (which then trickles down to effective altruism), is not a quirk, or a bug, but rather a feature of utilitarian philosophy, and can be found in even the smallest drop. And why I am not an effective altruist is that to deal with it one must dilute or swallow, swallow or dilute, always and forever.

The current popularity of effective altruism is, I think, the outcome of two themselves popular philosophical thought experiments: the “trolley problem” and the “shallow pond.” Both are motivating thought pumps for utilitarian reasoning.

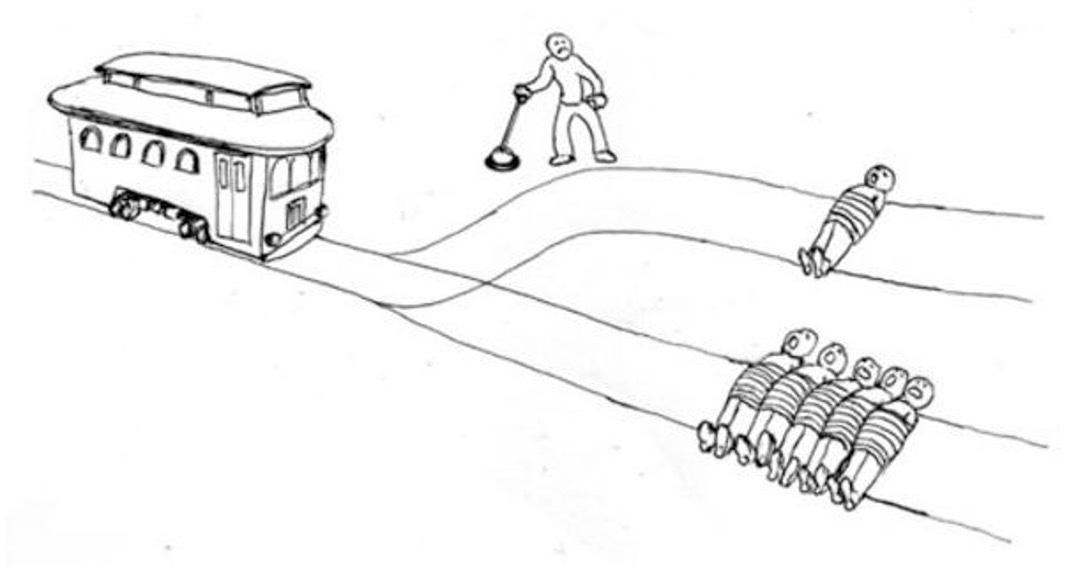

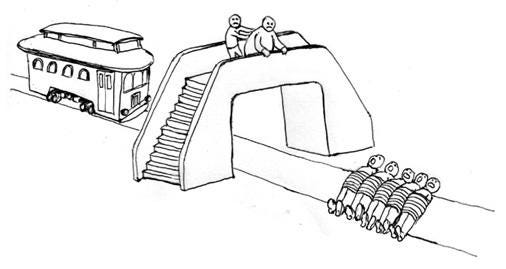

The trolley problem is a meme almost everyone knows at this point: a trolley is about to run over five people. Do you switch it to a different track with one person instead?

I remember first being introduced to the trolley problem in college (this was B.M., “Before Memes”). People were asked to raise our hands if we would pull the lever to switch the tracks, and the majority of people did. But then the professor gave another example: What if instead you have the opportunity to push an obese person onto the tracks, and you somehow have the knowledge that this would be enough slow the trolley and save the five? Most people in class didn’t raise their hands for this one.

Maybe all those people just didn’t have the stomach? That’s often the utilitarian reply, but the problem is that alternative versions of the deceptively simple trolley problem get worse and worse, and more and more people drop off in terms of agreement. E.g., what if there’s a rogue surgeon who has five patients on the edge of organ failure, and goes out hunting the streets at night to find a healthy person, drags them into an alley, slits their throat, then butchers their body for the needed organs? One for five, right? Same math, but frankly it’s a scenario that, as Russell said of forcing inexperienced girls to to bear syphilitic children: “. . . nobody whose natural sympathies have not been warped by dogma. . . could maintain that it is right and proper that that state of things should continue.”

The poison for utilitarianism is that it forces its believers to such “repugnant” conclusions, like considering an organ-harvesting serial killer morally correct, and the only method of avoiding this repugnancy is either to water down the philosophy or to endorse the repugnancy and lose not just your humanity, but also any hope of convincing others, who will absolutely not follow where you are going (since where you’re going is repugnant). The term “repugnant conclusion” was originally coined by Derek Parfit in his book Reasons and Persons, discussing how the end state of this sort of utilitarian reasoning is to prefer worlds where all available land is turned into places worse than the worst slums of Bangladesh, making life bad to the degree that it’s only barely worth living, but there are just so many people that when you plug it into the algorithm this repugnant scenario comes out as preferable.

To see the inevitability of the repugnant conclusion, consider the other popular thought experiment, that of the drowning child. Written in the wake of a terrible famine in Bengal, Peter Singer gives the reasoning of the thought experiment in his “Famine, Affluence, and Morality.”

. . . if I am walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning in it, I ought to wade in and pull the child out. This will mean getting my clothes muddy, but this is insignificant, while the death of the child would presumably be a very bad thing. . . It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor's child ten yards from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away.

And all that sounds very good—who would not soil their clothes, or pay the equivalent of a dry cleaning bill, to save a drowning child? But when taken literally it leads, very quickly, to repugnancy. First, there’s already a lot of charity money flowing, right? The easiest thing to do is redirect it. After all, you can make the same argument in a different form: why give $5 to your local opera when it will go to saving a life in Bengal? In fact, isn’t it a moral crime to give to your local opera house, instead of to saving children? Or whatever, pick your cultural institution. A museum. Even your local homeless shelter. In fact, why waste a single dollar inside the United States when dollars go so much further outside of it? We can view this as a form of utilitarian arbitrage, wherein you are constantly trading around for the highest good to the highest number of people.

But we can see how this arbitrage marches along to the repugnant conclusion—what’s the point of protected land, in this view? Is the joy of rich people hiking really worth the equivalent of all the lives that could be stuffed into that land if it were converted to high-yield automated hydroponic farms and sprawling apartment complexes? What, precisely, is the reason not to arbitrage all the good in the world like this, such that all resources go to saving human life (and making more room for it), rather than anything else?

The end result is like using Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World as a how-to manual rather than a warning. Following this reasoning, all happiness should be arbitraged perfectly, and the earth ends as a squalid factory farm for humans living in the closest-to-intolerable conditions possible, perhaps drugged to the gills. And here is where I think most devoted utilitarians, or even those merely sympathetic to the philosophy, go wrong. What happens is that they think Parfit’s repugnant conclusion (often referred to as the repugnant conclusion) is some super-specific academic thought experiment from so-called “population ethics” that only happens at extremes. It’s not. It’s just one very clear example of how utilitarianism is constantly forced into violating obvious moral principles (like not murdering random people for their organs) by detailing the “end state” of a world governed under strict utilitarianism. But really it is just one of an astronomical number of such repugnancies. Utilitarianism actually leads to repugnant conclusions everywhere, and you can find repugnancy in even the smallest drop.

How can the same moral reasoning be correct in one circumstance, and horrible in another? E.g., while the utilitarian outcome of the trolley problem is considered morally right by a lot of people (implying you should switch the tracks, although it’s worth noting even then that plenty disagree) the thought experiment of the surgeon slitting innocent throats in alleys is morally wrong to the vast majority of people, even though they are based on the same logic. Note that this is exactly the same as our intuitions in the shallow pond example. Almost everyone agrees that you should rescue the child but then, when this same utilitarian logic is instead applied to many more decisions instead of just that one, our intuitions shift to finding the inevitable human factory-farms repugnant. This is because utilitarian logic is locally correct, in some instances, particularly in low-complexity ceteris paribus set-ups, and such popular examples are what makes the philosophy attractive and have spread it far and wide. But the moment the logic is extended to similar scenarios with slightly different premises, or the situation itself complexifies, or the scope of the thought experiment expands to encompass many more actions instead of just one, then suddenly you are right back at some repugnant conclusion. Such a flaw is why the idea of “utility monsters” (originally introduced by Robert Nozick) is so devastating for utilitarianism—they take us from our local circumstances to a very different world in which monsters derive more pleasure and joy from eating humans than humans suffer from being eaten, and most people would find the pro-monsters-eating-humans position repugnant.

To give a metaphor: Newtonian physics works really well as long as all you’re doing is approximating cannon balls and calculating weight loads and things like that. But it is not so good for understanding the movement of galaxies, or what happens inside a semiconductor. Newtonian physics is “true” if the situation is constrained and simple enough for it to apply to; so too it is with utilitarianism. This is the etiology of the poison.

Unwilling to abandon their philosophy merely because it is poisonous, some simply swallow it whole. This is the “shut up and multiply” approach of, e.g., Eliezer Yudkowsky, who writes in his Sequences that:

This isn’t about your feelings. A human life, with all its joys and all its pains, adding up over the course of decades, is worth far more than your brain’s feelings of comfort or discomfort with a plan. Does computing the expected utility feel too cold-blooded for your taste? Well, that feeling isn’t even a feather in the scales, when a life is at stake. Just shut up and multiply.

(Given that this is a critical essay and I am mentioning him individually, I should point out that on other issues I think Yudkowsky has been presciently correct, e.g., in sounding the alarm early about AI safety). But swallowing whole the poison of utilitarianism leads to ethical conclusions that are impossible to take seriously. For example:

. . .pick some trivial inconvenience, like a hiccup, and some decidedly untrivial misfortune, like getting slowly torn limb from limb by sadistic mutant sharks. If we’re forced into a choice between either preventing a googolplex people’s hiccups, or preventing a single person’s shark attack, which choice should we make? If you assign any negative value to hiccups, then, on pain of decision-theoretic incoherence, there must be some number of hiccups that would add up to rival the negative value of a shark attack. For any particular finite evil, there must be some number of hiccups that would be even worse.

No. There isn’t. Evils and goods are not what is called “well-ordered.” Mathematically, this means that they cannot all be ranked in a gigantic set, from greatest to least, objectively, and so be added and subtracted against each other. The reason is that there are qualitative, not just quantitative, differences between various positive and negative things, which ensures there can never be a simple universal formula. And the vast majority of people can see these qualitative differences, even if they rarely articulate them. E.g., hiccups are such a minor inconvenience that you cannot justify feeding a little girl to sharks to prevent them, no matter how many hiccups we’re talking about. Goods and evils are instead what’s called a partially-ordered set, that is, some are comparable, and can be ranked against each other, and others aren’t. The utilitarian, starting from the (gargantuan) assumption that morality is just calculations along a well-ordered set of good and evil outcomes, is forced into repugnant conclusions over and over every time they compare things that aren’t local in the set, or when they hit a particularly convoluted part of it. E.g., if you had the cure for hiccups in one hand, and a little girl in the other, and a bunch of sharks below, the expected value supposedly says you should drop the little girl. Yet, if one could put it to an immediate planetary-wide vote (maybe you’re a very popular live-streamer in this scenario), the obvious result would come in: “We don’t care if we occasionally get the hiccups a couple times a year, it’s only a minor inconvenience, hiccups are totally incomparable to this girl being eaten alive, please save the girl.” The response would come in this way because most people recognize that the “evil” of a hiccup is not qualitatively the same kind of “evil” as feeding a little girl to sharks, in the same way that the “good” of putting on warm socks is not the same as the “good” of saving a little girl from sharks. But the utilitarian, veins coursing with swallowed poison, must say back to the people of the planet: “Your votes are driven by your feelings. Shut up and multiply.” And then drops the girl.

What the utilitarian doesn’t understand is that people’s feelings are not just random feelings—they reflect that most people don’t buy the background assumption of the utilitarian. Indeed, think how incredibly lucky we would have to be to live in a universe where every possible situation can be judged via a knowable finite algorithm as more or less moral than every other possible situation, and, furthermore, that comparing these situations involves mere addition and subtraction, multiplication and division—such a belief almost necessitates platonism, or perhaps even divine creation. Like most beliefs of this kind, it is a result of not understanding Wittgenstein’s point that the definitions of words, like “good” or “evil,” do not refer to some essential property, but rather a family-resemblance; apples to apples makes sense, but apples to oranges changes the equation irreducibly.

And an arbitrage trade between two things that aren’t actually equal leads to a constant worsening of the world, since you are not actually trading like to like. Here it is perhaps worth noting that one of the main sources of funding for effective altruism, Sam Bankman-Fried, began down his path to billionaire-hood (just a few months after being the head of an effective altruist organization) by taking advantage of a notorious case of arbitrage when in 2017 the price of Bitcoin in Japan rapidly outran the price in America—Bankman-Fried was selling in Japan every day, buying in America every day, over and over, until the price of the two equalized. You get rich doing this in the world of economics, but the problem in applying it everywhere is that morality is not a market.

The other popular response to the poison is one that I personally find more palatable, albeit still unconvincing, which is its dilution. I say palatable because, as utilitarianism is diluted, it loses its teeth, and so becomes something amorphous like “maximize the good you want to see in the world, with good defined in a loose, personal, and complex way” or “help humanity” or “better the world for people” and almost no one can disagree with these sort of statements. In fact, they verge on vapidity.

Proponents of dilution admit that just counting up the atomic hedonic units of pleasure or pain (or some other similarly reductive strategy) is indeed repugnant. Perhaps, they say, if we plugged in meaning to our equations, instead of merely pleasure or suffering, or maybe weighted the two in a some sort of ratio (two cups of meaning to one cup of happiness, perhaps), this could work! The result is an ever-complexifying version of utilitarianism that attempts to avoid repugnant conclusions by adding more and more outside and fundamentally non-utilitarian considerations. And any theory, even a theory of morality, can be complexified in its parameters until it matches the phenomenon it’s supposed to be describing.

Upset that it would technically increase the net happiness in the universe to let necrophiliacs sexually abuse dead dogs in secret, and therefore you should encourage this practice? Add in some non-utilitarian extra axioms to make sure this particular repugnancy doesn’t happen. Just as how Ptolemy accounted for the movements of the planets in his geocentric model by adding in epicycles (wherein planets supposedly circling Earth also completed their own smaller circles), and this trick allowed him to still explain the occasional paradoxical movement of the planets in a fundamentally flawed geocentric model, so too does the utilitarian add moral epicycles to keep from constantly arriving at immoral outcomes.

“Well, what if we change from only caring about absolute amounts of happiness or pleasure and instead try to maximize the meaning in people’s lives?” Epicycle added. “We could value things like freedom above and beyond moral worth of sheer numbers of happy people.” Epicycle added. “What if we calculate the total sum of expected happiness in the remainder of the universe, all the way out till its end, for any particular action?” Incalculable epicycle added. “Maybe we need to have special rules around negative causation, like distinguishing between doing and allowing.” Epicycle added. And often such additions simply bring on other repugnancies, e.g., “What if we take the average happiness instead?” quickly leads to the repugnant conclusion that one should prefer a single happy individual over a planet of unhappy individuals—but all the epicycles are like that, just more Newtonian physics describing things that aren’t fundamentally Newtonian.

So it goes, Greeks tweaking their star charts to match the movements of the heavens until the theory is as ugly as it is ungainly.

Which brings me to effective altruism. A movement rapidly growing in popularity, indeed, at such a pace that if it somehow maintains it, it may have as much to say about the future of morality as many contemporary religions. And I don’t think that there’s any argument effective altruism isn’t an outgrowth of utilitarianism—e.g., one of its most prominent members is Peter Singer, who kickstarted the movement in its early years with TED talks and books, and the leaders of the movement, like William MacAskill, readily refer back to Singer’s “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” article as their moment of coming to.

This means that, at least in principle, to me effective altruism looks like a lot of good effort originating in a flawed philosophy. However, in practice rather than principle, effective altruists do a lot that I quite like and agree with and, in my opinion—and I understand this will be hard to hear over the sound of this much criticism, so I’m emphasizing it—effective altruists add a lot of good to the world. Indeed, their causes are so up my alley that I’m asked regularly about my positions on the movement, which is one reason I wrote this. I think the effective altruist movement is right about a number of things, not just AI safety, but plenty of other issues as well, e.g., animal suffering. But you don’t have to be an effective altruist to agree with them on issues, or to think they have overall done good.

However, due to its origins in utilitarianism, the effective altruist movement is itself always drawn toward the exact same repugnancy, and faces the same choice to either dilute it or swallow it. One can see repugnant conclusions pop up in the everyday choices of the movement: would you be happier being a playwright than a stock broker? Who cares, stock brokers make way more money, go make a bunch of money to give to charity. And so effective altruists have to come up with a grab bag of diluting rules to keep the repugnancy of utilitarianism from spilling over into their actions and alienating people. After all, in a trolley problem the lever is right in front of you and your action is compelled by proximity—but in real life, this almost never happens. So the utilitarian must begin to seek out trolley problems. Hey, you, you’re saving lives in Nigeria? How about you go to Bengal? You’ll get more bang for your buck there. But seeking out trolley problems is becoming the serial killer surgeon—you are suddenly actively out on the streets looking to solve problems, rather than simply being presented with a lever.

Therefore, the effective altruist movement has to come up with extra tacked-on axioms that explain why becoming a cut-throat sociopathic business leader who is constantly screwing over his employees, making their lives miserable, subjecting them to health violations, yet donates a lot of his income to charity, is actually bad. To make the movement palatable, you need extra rules that go beyond cold utilitarianism, otherwise people starting reasoning like: “Well, there are a lot of billionaires who don’t give much to charity, and surely just assassinating one or two for that would really prompt the others to give more. Think of how many lives in Bengal you’d save!” And how different, really, is pulling the trigger of a gun to pulling a lever?

For when I say the issues around repugnancy are impossible to avoid, I really mean it. After all, effective altruists are themselves basically utility monsters. Aren’t they out there, maximizing the good? So aren’t their individual lives worth more? Isn’t one effective altruist, by their own philosophy, worth, what, perhaps 20 normal people? Could a really effective one be worth 50? According to Herodutus, not even Spartans had such a favorable ratio, being worth a mere 10 Persians.

Of course, all the leaders of the effective altruist movement would at this point leap forward to exclaim they don’t embrace the sort of cold-blooded utilitarian thinking I’ve just described, yelling out—We’ve said we’re explicitly against that! But from what I’ve seen the reasoning they give always comes across as weak, like: uh, because even if the movement originates in utilitarianism unlike regular utilitarianism you simply aren’t allowed to have negative externalities! (good luck with that epicycle). Or, uh, effective altruism doesn’t really specify that you need to sacrifice your own interests! (good luck with that epicycle). Or, uh, there’s a community standard to never cause harm! (by your own definition, isn’t harm caused by inaction?). Or, uh, we simply ban fanaticism! (nice epicycle you got there, where does it begin and end?). So, by my reading of its public figures’ and organizations’ pronouncements, effective altruism has already taken the path of diluting the poison of utilitarianism in order to minimize its inevitable repugnancy, which, as I’ve said, is a far better option than swallowing the poison whole.

I mean, who, precisely, doesn’t want to do good? Who can say no to identifying cost-effective charities? And with this general agreeableness comes a toothlessness, transforming effective altruism into merely a successful means by which to tithe secular rich people (an outcome, I should note, that basically everyone likes). But the larger problem for the effective altruist movement remains that diluting something doesn’t actually make it not poison. It’s still poison! That’s why you had to dilute it. It’s just now more fit for public consumption than it was without the dilution.

One thing I very much like about effective altruism is how much more attention they pay to online writing than other communities—perhaps as a young and energetic movement they are ahead of the curve in their preferences (or so I’d like to think). An effective altruist organization even once gave some funding to me. Indeed, this very essay, which I’d long planned to write some version of, is coming out now because the same effective altruist organization is offering a $20,000 prize to whomever gives the best critique of effective altruism this month. A thing I find admirable, if slightly masochistic (he says as he literally bites the hand that feeds him). Unfortunately, my criticism is how the utilitarian core of the movement is rotten, and I think that’s the part anyone in the movement least wants to see criticized, since there’s almost nothing they can do about it if the core is indeed wrong. E.g., in the guidelines of the contest they write that they are looking for:

. . . we would be most interested in arguments that recommend some specific, realistic action or change of belief.

My worry is that such a guideline will lead trivial or inconsequential criticisms, since asking for suggestions means restricting it to constructive criticism. But why I am not an effective altruist is because, from what I’ve seen, the issues go beyond what’s fixable via constructive criticism. While plenty of academic papers try to address the repugnant conclusion (often, in my opinion, making the mistake of it being some overly-specific problem involving only population and “mere addition”), the main result in the literature has been that repugnant conclusions are basically impossible to avoid when using the utilitarian approach writ broadly. In fact, plenty of the leading proponents of effective altruism write entire papers about these problems and arrive at very pessimistic conclusions. E.g., here’s the conclusion to an academic paper on how poorly utilitarianism does in extreme scenarios of low probability but high impact payoffs, written in 2021 by the the CEO of the effective altruist FTX Foundation, the very organization giving out the $20,000 criticism prize for this contest:

In summary, as far as the evaluation of prospects goes, we must be willing to pass up finite but arbitrarily great gains to prevent a small increase in risk (timidity), be willing to risk arbitrarily great gains at arbitrarily long odds for the sake of enormous potential (recklessness), or be willing to rank prospects in a non-transitive way. All options seem deeply unpalatable, so we are left with a paradox.

In other words, the attempted academic answers by utilitarians are what I’ve already outlined, merely presented more technically and focused much more on specific instances, for which they either import esoteric epicycles from non-utilitarian moral theories to dilute the poison, or come up with increasingly arcane justifications to swallow the poison (one such reason to swallow it, they tautologously conclude, is that the poison is unavoidable!). Occasionally they just throw up their hands. Yet, even as these problems crop up in a large academic literature, most utilitarians are unwilling to question why they are dealing with a poison in the first place. Whereas I’m of the radical opinion that the poison means something is wrong to begin with.

So here’s my official specific and constructive suggestion for the effective altruism movement: People are always going to be off-put by the inevitable repugnancy, so to convince more people and grow the movement, keep diluting the poison. Conceptualize this however you need to. Internally, just say the normies don’t have the stomachs of steel you have. Your reasons why don’t matter. What matters is you dilute, in fact, dilute it all the way down, until everyone is basically just drinking water. You’re already on the right path. Do things like start calling it “longtermism” and make it just about caring about the future of humanity and reducing existential risk, which few people can argue with, and which can be justified in many ways. Under a big tent, let a thousand flowers bloom! Take rich people’s money and give it to your friends doing weird projects! Throw cash at AI safety even if we have no actual idea if it’s better than buying mosquito nets! Fork it over to Mars colonization! Does building a city on Mars really do that much to solve existential risk? Maybe some, but the real reason to do it is going to space is awesome and epic—so mine an asteroid or something! Pioneer new ways of giving via micro-grants! Will they work better than standard charities? They’ll be better at some things, worse at others, kind of a wash actually! Fund batshit science like my own field, the science of consciousness, or crazy young theoretical physicists looking for theories of everything with a chance of finding one similar to, oh, about being struck by lightning. Can’t figure out how giving blogs $100,000 in prize money is worth dozens of Bengalis being supported for life? Or preventing 1,000 cases of third-world blindness? It doesn’t matter! Basically, just keep doing the cool shit you’ve been doing, which is relatively unjustifiable from any literal utilitarian standpoint, and keep ignoring all the obvious repugnancies taking your philosophy literally would get you into, but at the same time also keep giving your actions the epiphenomenal halo of utilitarian arbitrage, and people are going to keep joining the movement, and billionaires will keep donating, because frankly what you’re up to is just so much more interesting and fun and sci-fi than the boring stuff others are doing.

I realize this suggestion may sound glib, but I really do think that by continuing down the path of dilution, even by accelerating it, the movement will do a lot of practical good over the next couple decades as it draws in more and more people who find its moral principles easier and easier to swallow. A back of a napkin is all you need, and the utilitarian calculations can be treated as what they are: a fig leaf.

What I’m saying is that, in terms of flavor, a little utilitarianism goes a long ways. And my suggestion is that effective altruists should dilute, dilute, dilute—dilute until everyone everywhere can drink.

Seems to me that the standard approach to criticizing any philosophy - personal, political, economic,... - is to use exceptions to negate the rule (except for when your own philosophy is in the firing line).

The hubristic notion that humans can develop (or is it identify?) a rule that can cover all situations is the source of so much animosity AND idiocy. Humans are flawed and limited, so anything that results from their efforts will be flawed and limited.

Why can't we just accept that and "pursue perfection" instead of "demanding perfection". Perfection can never be attained, but pursuit of it is a worthwhile activity.

This is my favorite piece of your writing to date. I share your perception of utilitarianism, and I thought this was a great, timeless meta-summary of the ways it goes crazy but also why EA is good in the short-term. Much of my conflicts with EA come from their self-professed criteria that, for a problem to be suitable for EA, it must be important, neglected, and tractable. Neglect seems like a cop-out from trying to contribute to popular things that are still incredibly important, and tractable is so subjective that it could justify whatever you want (ex: AI safety doesn't seem tractable because we don't actually know if or how to generate machine consciousness, but math PhDs swear it's tractable and thus we have Yud's AI death cult. Meanwhile, permitting reform seems really important, but math PhDs say "not tractable" because you'd have to build a political coalition stronger than special interests and if it's not solvable with a blog post or LaTex, it's impossible.)