NASA and SpaceX are establishing the first Martian city by 2030

The gates of the wonder world are opening in our time

When the Space Shuttle retired in 2011, stranding the USA without access to orbit, it took a retirement tour around the country. As it was carted from city to city the images played out nation-wide in funereal Americana. Despite the uplifting rhetoric and crowds, it was clear on TV we were watching a casket be carried out, and it seemed then inevitable my generation would be Earth-bound our whole lives.

What a difference a decade makes, no?

Developments in the space industry are occurring faster than at any time since the Apollo era—no, faster. And the ones setting the quick tempo for everyone else are at SpaceX. Down in Boca Chica, Texas, where they are building their massive reusable rocket Starship, the construction has been impressive, speedy, and very public. Every day drones buzz over the site to take photos for the multiple news shows that just follow SpaceX development—that’s how much is going on. And there’s no doubt the company’s aim is a city on Mars.

Their momentum is why, when I originally posted my predictions for 2050, the first prediction was the existence of a city on Mars. A common (and reasonable) reply was “You criticize other futurists for making too far-fetched predictions, but your very first one is a Martian city by 2050, which is itself far-fetched.” Such skepticism would have been warranted even just back in 2013, but then SpaceX captured 30% of the global market share of commercial launch contracts in 2013, and by 2018 this doubled, up to 65%. I think it reasonable, at this point, to believe the hype.

Still, all this stuff is so new it’s not quite in the public eye. It was only last month that authors from both NASA and SpaceX released an initial joint white paper for the proposed Martian city, named by SpaceX “Starbase Alpha.”

The construction of this city will be dependent on SpaceX’s flagship project: the Starship. It’s a still-in-development massive but reusable rocket, the largest ever made. Designed to be mass-produced out of (relatively) cheap stainless steel, it has a streamlined architecture with as few parts as possible, and will be able to both land on and take off from its extraterrestrial destinations. In the future, expect to have fleets of Starship where dozens leave together for Mars during launch windows, operating like a space caravan.

Pollyannish? Even within the space industry, many simply don’t understand how much of an advance Starship represents in terms of making space transport cheaper by orders of magnitude. Space industry blogger Casey Handmer writes that:

Starship is designed to be able to launch bulk cargo into LEO [low Earth orbit] in >100 T chunks for <$10m per launch, and up to thousands of launches per year. By refilling in LEO, a fully loaded deep space Starship can transport >100 T of bulk cargo anywhere in the solar system, including the surface of the Moon or Mars, for <$100m per Starship. Starship is intended to be able to transport a million tonnes of cargo to the surface of Mars in just ten launch windows.

100 tons of bulk cargo into space for less than $100 million. That’s as much as single launches have cost in some cases! In comparison, the average cost to launch 100 tons of mass into space between 1970 and 2000 was well over a billion dollars, something like $1,677,950,000. That’s an order of magnitude reduction, which changes the economic cost-benefit ratio of space travel entirely.

Another fact that’s gone under-appreciated is that the Starship’s fuel source, unlike all other rockets, is methane, which can be made using raw materials available throughout the solar system (humans will basically just be farting from planet to planet). Rockets can’t take their return fuel with them, but Starships can uniquely travel to planets or moons, and, as long as methane can be made there like it can be on Mars, refuel for a return trip.

But at first Starships won’t return at all. The white paper says that:

The first set of Starships launched to Mars will be uncrewed and are intended to demonstrate the capability to successfully launch from Earth and land on Mars with human-scale lander systems. These uncrewed vehicles will also provide the opportunity to deliver significant quantities of cargo to the surface in advance of human arrival. . . In addition, such missions could enable delivery of mobile robotic assets that could be used to conduct planetary science research either autonomously or through high-latency teleoperation.

This last idea of using the early Starships as one-offs to deliver NASA rovers ('“robotic assets”) is, in my opinion, unlikely to occur—in fact, I think it’s possible there’ll be minimal NASA technological involvement in the first Starships to Mars, a telling indication that the tip-of-the-spear development has firmly switched from public to private. NASA is just too slow. This might sound like undue criticism, but consider the James Webb telescope. It was supposed to launch in December of this year, but that’s already a hefty delay from its originally scheduled launch in 2007, and it was just delayed again this month because, ah, they dropped it.

So it’s quite possible NASA will be in the position where someone says: “Hey, hop in, we’re going to Mars and we got space for a robot” and they’ll have to reply “Sorry, it will take us five years to build a rover for this mission, can’t you just wait a tick?”

While these first ships obviously won’t be crewed, when they are, what will the journey be like? Well:

Crewed Starships will have on the order of 1100 [cubic meters] forward space (most of which will be pressurized for human habitation).

This is about the size of a third of an Olympic swimming pool. That may seem quite small, and it is, but consider this distribution of average residential space occupants have in different countries:

That tiny box at the front labeled “HK” is Hong Kong (only 15 square meters of floor space). Even if only half of the proposed 1,100 cubic meters is residential, at 20 people that’s ~22 cubic meters per person, which is around the size of a smaller bedroom. Obviously it will be divided up into commons and sleeping quarters, but given that some people here on Earth sleep in tubes, it seems doable, and the math changes dramatically if it’s 12 people per ship instead of 20. According to the white paper:

Humans will likely live on the Starship for the first few years until additional habitats are constructed, so the radiation risk must be assessed and mitigated with equipment planned to support this initial infrastructure. The first wave of uncrewed Starship vehicles can also be relocated and/or repurposed as needed to support the humans on the surface. These vehicles will be valuable assets for storage, habitation, and as a source of refined metal structures and resources.

In other words, Starships are the habitats. They are the size of a small building, and can simply serve as such, parked.

What, precisely, will people do once they’re on Mars? I once made a friendly bet with researcher Simon DeDeo1 over at the Sante Fe Institute that the first crews of Mars would basically just be construction workers, and that construction on Mars would look pretty much like construction here on Earth, except that everyone will be wearing spacesuits. He bet that everything would be 3D-printed and made by remote-control robots by then, a very automated, non-human, and futuristic process. Now that we know more of the plan, it is indeed looking like we’ll be relying on human power, people living in the Starships themselves:

Current SpaceX mission planning includes the intention that these vehicles will also carry hardware needed to support the human base including equipment for increased power production, water extraction, LOX/methane production, pre-prepared landing pads, radiation shielding, dust control equipment, exterior shelters for humans and equipment, etc.

Much of this will be made, or parts made, here on Earth, but the construction on Mars will involve pretty much the stuff construction here does. The equipment will be tailored for the Martian environment, but in many cases, surprisingly familiar. Casey Handmer points out that:

After Starship, Caterpillar or Deere or Kamaz can space qualify their existing commodity products with very minimal changes and operate them in space. In all seriousness, some huge Caterpillar mining truck is already extremely rugged and mechanically reliable. McMaster-Carr already stocks thousands of parts that will work in mines, on oil rigs, and any number of other horrendously corrosive, warranty voiding environments compared to which the vacuum of space is delightfully benign. A space-adapted tractor needs better paint, a vacuum compatible hydraulic power source, vacuum-rated bearings, lubricants, wire insulation, and a redundant remote control sensor kit.

In other words, pretty minimal changes to get a tractor working on Mars. So if you want to imagine the future in ten years, picture a big Martian construction site busy with people in spacesuits driving John Deere tractors around. It is, in other words, frontier work. The aesthetics of human space colonization is Firefly, or the grit of the original Star Wars, not the sleek bureaucratic competence of Star Trek.

When should we expect the first dusty missions? According to the white paper:

SpaceX is aggressively developing Starship for initial orbital flights, after which they intend to fly uncrewed flights to the Moon and conduct initial test flights to Mars at the earliest Mars mission opportunity, potentially as soon as 2022, or failing that in the 2024 window.

These dates may sound preposterously close, given the spareness of the plans. However, Starship (originally introduced as the “Interplanetary Transport System”) has gone from being a gleam in SpaceX’s eye in 2016 to the last leg of development now. If this developmental pace is sustained, they might indeed just make the 2024 Earth-Mars launch window. That means humans could well have already broken ground on the construction of Starbase Alpha by 2030 and be living on Mars permanently.

I know such speculations sound fanciful, a classic case of counting chickens before hatching. There are a couple things that could slow this all down. First, perhaps SpaceX will run into possible financial troubles if it can’t get Starship working by next year. Alternatively, bad actors like Russia and China might launch a slew of anti-satellite debris into orbit, closing our pathway to space by making low Earth orbit too dangerous (also called “Kessler syndrome”). Another possible obstacle is political regulation based on concerns around space privatization by billionaires, i.e., a legislative fight between “Ups” (republicans, a large swath of democrats) and “Downs” (the progressive side of the Democratic party, like Bernie Sanders). But there’s a reason Carl Sagan called Mars “the wonder world.” Given its mythological hold over the human imagination, I’d be shocked if bipartisan support wasn’t broad enough to forestall preventative regulation.

I know a palpable giddiness when talking about space news reveals me as an “Up”—I’m not going to pretend to be objective here—but I do know not everyone feels that way. I at least try to be sympathetic to the Down point of view. In the end, the reasons for our colonizing another planet are vast and inexplicable. They are difficult to share, difficult to convince someone of—it’s like trying to convince someone to like a certain genre of music. You either feel the frontier vibe, or you don’t, and if you don’t feel it the whole thing seems over-the-top and chest-beating and unnecessary.

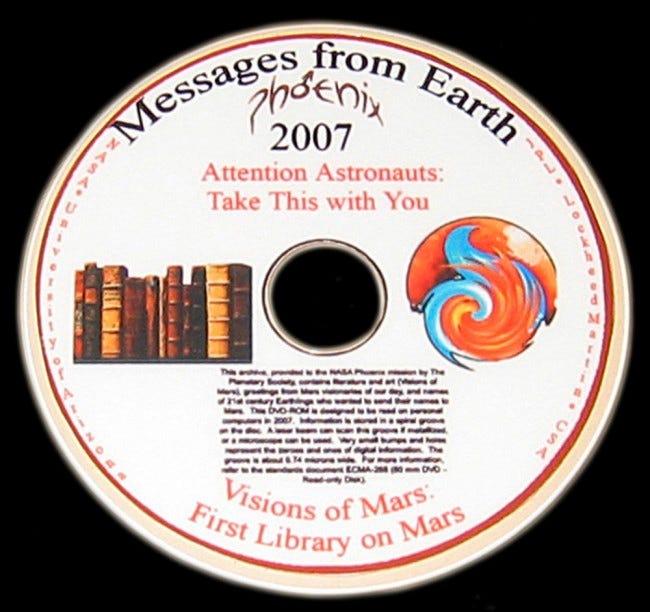

But let me give, perhaps, the most concrete possible reason I can think of to go to Mars: retrieving this DVD, a disk that sits on a defunct rover up near the Martian North Pole.

Stored on it are audio messages to future humans living on Mars, including some by Carl Sagan and Isaac Asimov. A chorus of human voices waits for us on another planet. It was sent onboard part of the 2008 Phoenix Rover, and is Martian-weather proof, so will still be readable. A priceless historical artifact just sitting there in the open. To get it you’ll have to go during the summer period, or, if you go during the winter period, you’ll have to break the frozen layer of dry ice that coats the rover. For on Mars, it snows dry ice.

Sagan’s recording is of him speaking casually in front of a waterfall in Ithaca, New York. Unsaid is that he is dying of a rare bone marrow disease at the age of 62. He thrums in his distinctive voice:

I don't know why you're on Mars . . . Maybe we're on Mars because we recognized that if there are human communities in many worlds, the chances of us being rendered extinct by some catastrophe on one world is much worse. Or maybe we're on Mars because of the magnificent science that can be done there, that the gates of the wonder world are opening in our time. Or maybe we're on Mars because we have to be. Because there is a deep nomadic impulse built into us by the evolutionary process. We come, after all, from hunter-gatherers. And for 99.99 percent of our tenure on Earth, we've been wanderers. And the next place to wander to, is Mars. But whatever the reason you're on Mars is, I'm glad you're there, and I wish I was with you.

So here’s a reason to go to Mars: to physically get this disk. You can then drive the it back in your converted tractor to the habitat, kick the dust off your boots and hang up your suit, and maybe pour yourself a glass of precious whiskey, all so that you can listen to those recordings for the first time where they’re meant to be listened to. Perhaps then, as outside the habitat window red sand plays in patterns vast and inexplicable, revelations impossible to communicate will cut you so sweetly you’ll cry.

Water waster.

Simon DeDeo was sadly hounded off Twitter by an angry mob earlier this year, as so many bright people who participate in “the discourse” are.

Erik I love your optimism in this post. But while optimism is the best mental stance for a happy and useful life, it can result in naive battle plans. For example:

Re "Another possible obstacle is political regulation based on concerns around space privatization by billionaires" - yes, this is a likely and dangerous obstacle. The US government can kill the private space sector in the US anytime with unfriendly overregulation, and is all too likely to give in to cultural pressures against private spaceflight.

Musk & Bezos &co. should really consider preparing to move offshore just in case. I'm not joking.

To me the *only* thing that can keep the US on track to the Moon, Mars and beyond, is competition with China. Therefore, even though I dislike certain aspects of today's China, I'm a big fan of the Chinese space program. And if the West can't compete, then well, here's to China.

Erik I’m also an Up (and very proudly and unapologetically so), but perhaps stop using the terms Up and Down? They can be interpreted, um, differently, you know. Suggest Cosmists and Terrans.