The Internet You Missed: A Last 2025 Snapshot

TIP's community writing: Part 2 of 2

There are many internets. There are internets that are bright and clean and whistling fast, like the trains in Tokyo. There are internets filled with self-serious people pretending they’re in the halls of power, there are internets of gossip and heart emojis, and there are internets of clowns. There are internets you can only enter through a hole under your bed, an orifice into which you writhe.

Every year, paid subscribers of The Intrinsic Perspective submit their writing, and I curate and share the results. As usual, I’m impressed by the talent on display.

This is Part 2. I shared Part 1 months back, and while I normally do pace installments out, their rather lengthy separation this year was not my fault, you see. As I’m sure you’ve noticed, time itself has sped up in 2025—in 2024 time, it’s only late September. As scientists will likely show any day now, this is a function of our consciousnesses rapidly shrinking in qualia volume, thanks to a “temporal squeezing” effect triggered by neural downsampling after watching even the tiniest amount of AI slop from the corner of your eye.

Still, the quality was truly exceptional this year, so I’m happy I got to read these, and choose some excerpts to share. Please note that:

I cannot fact check each piece, nor is including it an endorsement of its contents or arguments.

Descriptions of each piece, in italics, were written by the authors themselves, not me (but sometimes adapted for readability). I’m just the curator here.

I personally pulled the excerpts and images from each piece after some thought, to give a sense of them.

So here is their internet, or our internet, or at least, the shutter-click frozen image of one possible internet.

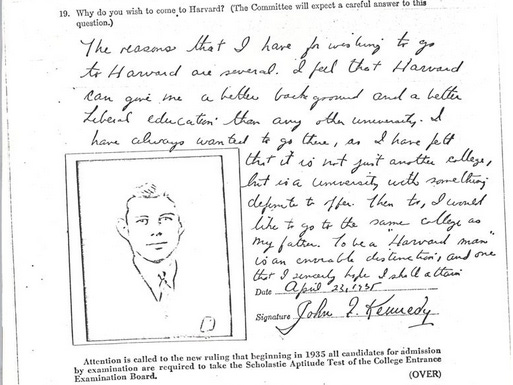

1. “JFK vs. Jeffrey Wang” by Samuel Kao.

Comparing two Harvard admissions essays, one from 1935 and the other from 2014, and showing how the American elite has changed for the worse.

For whatever reason I started thinking about an essay that AI startup entrepreneur Jeffrey Wang had written about studying at McDonald’s, which he used to apply successfully to several elite universities like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton in 2014….

I also remembered John F. Kennedy’s admissions essay to Harvard, which went viral some time ago for its risible—to a 21st century reader—brevity, and I thought Kennedy’s work was a useful counterpoint to Wang’s. Taken together, they provide an easy way to survey changes in elite selection in American society.

We will start with Wang’s essay, because it is a much richer text than Kennedy’s. Obviously, the prose is bad, but this is a high school essay, and I was not much better at that age. It is the very concept of the essay that is reviling. Juxtaposing the ostensibly lofty work of secondary school lucubrations with the quotidian environs of the suburban McDonald’s branch is a gimmick, and these gimmicks impress admissions officers, who are morons…. Too bad the essay is downright anti-intellectual. Here is the last sentence, which to Wang’s credit captures the essence of the whole work: “I’ve learned that contentment can exist in imperfect and unforeseen places when you simply observe your surroundings, adapt, and maybe even eat a French fry.” Precious words, but wholly without value.

2. “The Leviathan, the Hand, and the Maelstrom” by Nathan Witkin.

Social media and the smartphone are the technical bases of a new social institution that has, at great cost, ‘modernized’ the public square.

Put another way, while posts range widely in medium and significance, they are still all ‘content,’ in its cynical contemporary sense. What is ‘content’ in the way we now use this term if not an instance of communication… of secondary importance to its attentional ‘exchange’ value?

Projecting these developments forward, there is good reason to think we are on the cusp of a transition very similar to that experienced by the premodern exchange in goods. Premodern societies exchanged goods for a much richer variety of reasons—to mark rites of passage, to welcome outsiders, to send diplomatic signals, to pay feudal or religious tribute—only for the vast majority of these to be displaced by the formalized, Pareto-improving market transaction.

The rise of the Forum heralds something similar with respect to exchange in communication…. just as we do not know, or care to know most of the people we buy goods (and services) from, just as we often occupy completely different normative, cultural, and geographical spheres from them, our communicative behavior on the Forum—a rapidly rising proportion of our communicative behavior as such—is impersonal and transactional.

3. “Why a Random Stranger Would Read Your Fiction Book” by Sieran Lane.

How to make your fiction book look attractive to a random reader who has never heard of you.

A while ago, my nonfiction writing coach gave us feedback on our work. He said to a classmate, let’s call her Rini, that she shouldn’t name her Substack “Rini’s Journey.”

He asked, “Why would a random reader on the internet care about someone they don’t know called Rini?”

She was a little upset by that remark.

It made me think more, too. Our nonfiction coach trained us to scan headlines to see if we, as random strangers, would care enough to click on them.

With nonfiction, this is fairly straightforward to do. If the title is interesting or relevant to my life, then I might click it….

But with fiction, how do you grab someone’s attention?

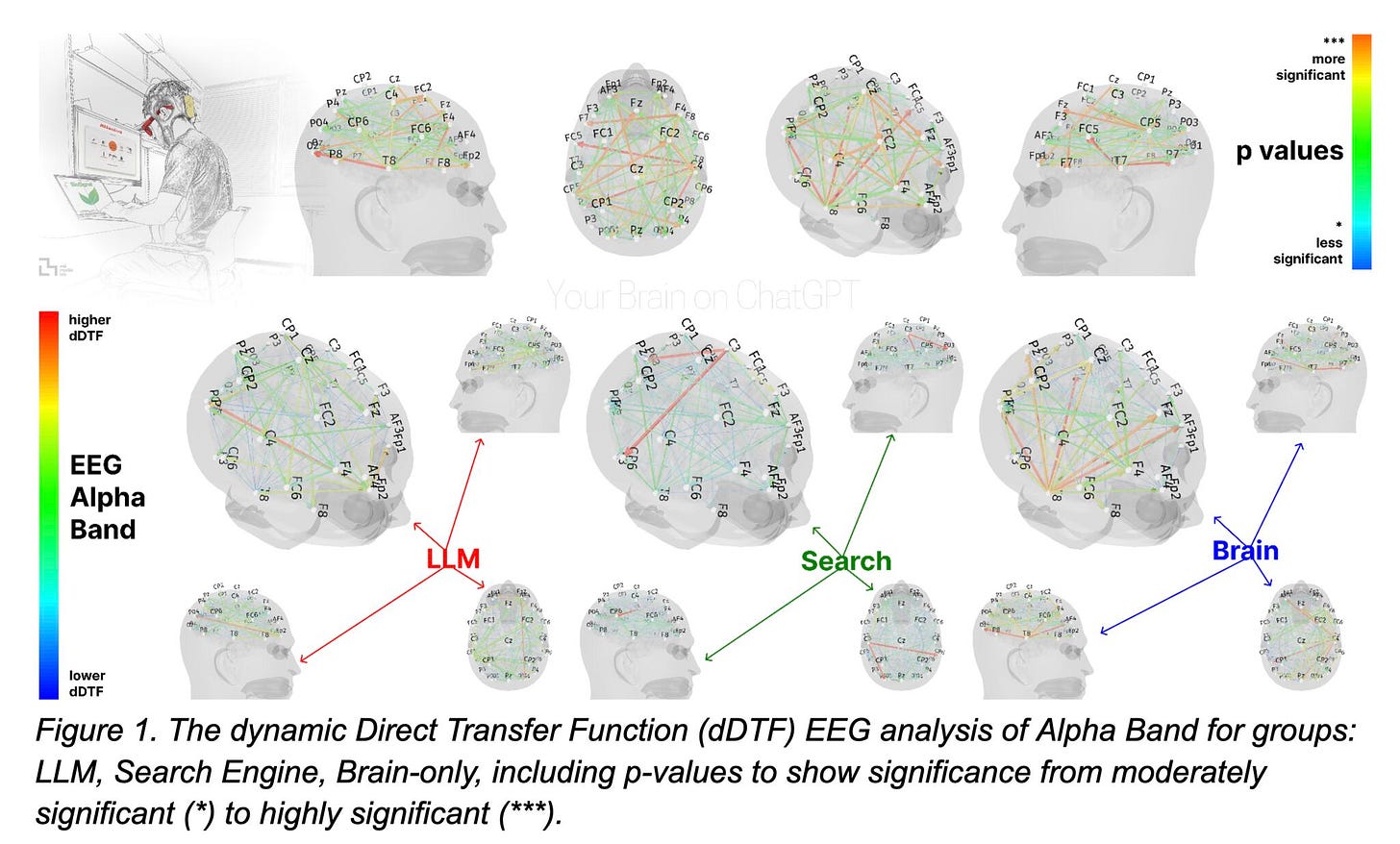

4. “We’re not getting Dumber” by Alejandro “Kairon” Arango.

Are LLMs actually making people dumber? Or are we just measuring skills for a system that’s evolving into a different society?

The paper “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task“ by Nataliya Kosmyna, Eugene Hauptmann, et al., that’s been doing the rounds on LinkedIn and Twitter as of late, does outline some measured decrease in mental faculties in students….

The researchers found that “EEG revealed significant differences in brain connectivity: Brain-only participants exhibited the strongest, most distributed networks; Search Engine users showed moderate engagement; and LLM users displayed the weakest connectivity.” They also noted that “cognitive activity scaled down in relation to external tool use.”

But.

That’s only because they’re measuring the repeated performance over writing a single essay: once aided by AI, once aided by Google, once by themselves, and (optionally) once again using AI after having done it themselves. The study tracked 54 participants over four months, with researchers concluding that “LLM users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.”

Yeah, that’s one hell of a headline.

5. “The sky is psychedelic: why so many people see strange lights in the sky” by Joel Frohlich.

Why ambiguous lights in the sky are often perceived as having extraordinary significance within the framework of predictive processing and evolutionary psychology.

According to neuroscientist and author Erik Hoel, social contagion is the main culprit, no different than the social contagion that triggers a mass outbreak of spontaneous dancing in the streets. I see something in the sky I don’t recognize, I call it a drone, and you, being suggestible, also start interpreting lights you don’t recognize in the sky as drones. Exponential growth kicks in, and a misinformation outbreak ensues.

I certainly don’t disagree with this explanation. But I also don’t think it’s the full story….

In a manuscript that we recently uploaded to the preprint server ArXiv, we offer several related perceptual mechanisms to explain the drone flap. The first is what we call the principle of skyborne impoverishment. According to this principle, lights that appear in the sky are extremely impoverished compared with stimuli viewed elsewhere…. Without context, distance, shape, or texture cues, a given light in the sky could be just about anything.

…. given our ancestral history, the human mind, it seems, has evolved to perceive deep meaning in the sky. And so, when we do look up, we see profundity rather than triviality. In short, we tend not to shrug off ambiguous lights in the sky because the sky is psychedelic.

6. “Are minds made of wonder?” by Oshan Jarow.

On his mother’s peculiar recovery from brain surgery, how some of the frontiers of consciousness science are curving back around to the ideas of an 11th century Kashmiri philosopher, and the growing suspicion that awareness is something like wonder incarnate.

In her early 60s, my mother began fumbling her words a bit too often. Around Christmas of 2022, we all began to notice. Her sentences would stop short, and she’d look around, as if someone had swooped in and stolen the word she intended to use. Did anyone see where it went?

English is her second language. And she still seemed quick as ever with her French, though mine was broken enough that I couldn’t be sure. So maybe, we thought, she was fine. Just getting old.

A few months later, either by dumb luck or divine intervention, she slammed the side of her head on the corner of an opened kitchen cabinet so hard she vomited. My sister brought her to the hospital, where they confirmed that yes, she had a mild concussion.

That’s when they noticed the tumor.

7. “Linguistic DNA of South Asian languages” by Pooja Babu.

On the unique sound that is prevalent in the languages of South Asia.

How do you identify if someone is a South Asian or from the Indian subcontinent? Ask them to pronounce ṭ (as in ṭamāṭar in Hindi), ḍ (as in ḍamaru in Hindi), ṇ (as in prāṇ in Hindi), ḷ (as in maḷe in Kannada or the Marathi ळ), and ṣ (as in puruṣ in Hindi), and you will know.

… linguists propose that this feature was slowly integrated into Sanskrit after the migration in a two-step assimilation process. Initially, these sounds entered into Sanskrit when the migrants, who were mostly men, came to the subcontinent and started mingling with the local women, who spoke some version of the Dravidian language with the retroflex sounds. These migrants procreated with the local women to keep their lineage. Their children, raised by their mothers, spoke their “mother tongue” while growing up and later learned to speak the “father tongue,” in this case, Sanskrit.

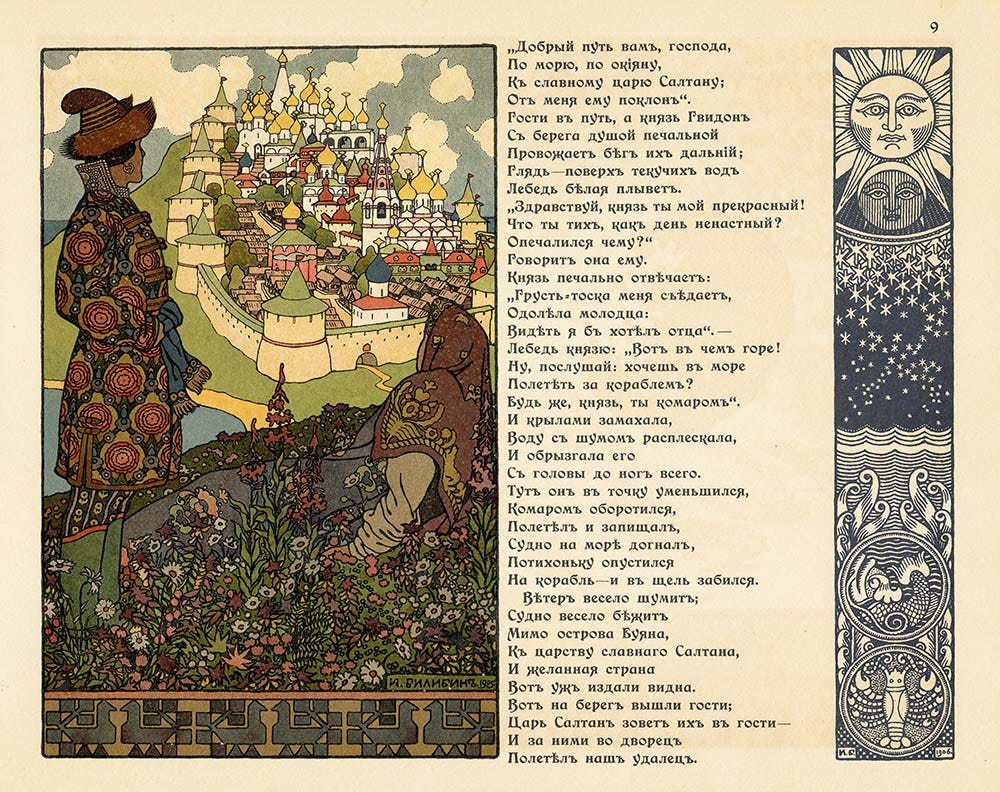

8. “Man of the People” by Story Ponvert, published in Lapham’s Quarterly.

A historical vignette about obscene 19th-century Russian folktales and nationalism.

Rudeness has consequences in fairy tales. Strangers met on the road may be more than they seem, so politeness is prudent. If a farmer is working his land and a passing old man asks what he’s sowing, he had better not answer, “I’m sowing cocks!” if he doesn’t want three-foot-tall phalluses sprouting in his field at harvest time.

9. “And Death Shall Have No Dominion” by Patrick Jordan Anderson.

An interpretation of the tech-entrepreneur Bryan Johnson’s bid for biological immortality as a manifestation of modern mainstream cultural assumptions, read through the lens of Ernest Becker’s 1973 classic, The Denial of Death.

If you know anything about Bryan Johnson, it is likely his much-publicized 2-million-dollar annual outlay on a personalized health regimen designed to slow—or, as he insists, actually to reverse—his rate of biological aging, and to vastly outperform the biblical allotment of threescore years and ten. In a characteristically audacious tweet from the start of this year, Johnson boasted that he is “by measurable standards, the healthiest person alive.”

Made wealthy by his years as founding CEO of the online payment company Braintree, which was later merged with Venmo and absorbed by PayPal, this would-be Methuselah has devoted his life and body, and foregone no expense, in pushing the boundaries of human longevity.

10. “The Memory Paradox: Why Our Brains Need Knowledge in an Age of AI” by Barbara Oakley (and her co-authors, this is a scientific paper).

A neuroscience-based explanation for the observed reversal of the Flynn Effect—the recent decline in IQ scores in developed countries—linking this downturn to shifts in educational practices and the rise of cognitive offloading via AI and digital tools… Countries that have adopted constructivist, student-centered approaches to education, despite their well-meaning intent, appear to have formed ground zero in the implosive decline of cognition observed in Western countries over the past fifty years. Yet in response, Western educators are simply throwing their hands up in the air and saying “it isn’t us—it’s that darned tiktok mentality!”

The cognitive offloading trends described in the previous section raise an important question: Could these widespread shifts in how we store and access information have measurable effects on cognitive abilities at a population level? If educational practices and daily habits increasingly favor external memory storage over internal knowledge building, we might expect to see these changes reflected in standardized measures of cognitive performance. The Flynn Effect and its recent reversal offer a revealing window into this possibility….

11. “But I have to have things my own way to keep me in my youth” by Dirk von der Horst.

In which music, one-night stands, and bitcoin find a common theme.

If I could rewrite the story of my life, there’d be a high school sweetheart I married. When I was a kid, our neighbors Stuart and Angelo modeled a gay relationship in which two men were simply inseparable, and I think they set up a sense that that kind of bond was a real possibility. But other factors got in the way of that being the set-up of my life, and my adulthood has basically been a coming-to-terms with singleness and getting to a point where the drop in sex drive means that’s a fact of life rather than a source of distress.

12. “Why Psychology Hasn’t Had a Big New Idea in Decades” by Ethan Ludwin-Peery.

How psychology might go from being a pre-paradigmatic to a paradigmatic science.

If psychology’s first paradigm does come from a major revolution, there’s a good chance it will involve the field splitting up, or different fields coming together. “Psychology” as a field may not survive any more than Alchemy or Natural Philosophy did. But it wouldn’t be wrong if we tear down our walls and use the stones to build something better, and we shouldn’t be afraid of the possibility that the resulting science might have a new name or new boundaries.

13. “Dream Now or Forever Hold your Peace” by Roger’s Bacon.

A meandering meditation on dreams, dwarves, gods, and what it means to be human in the age of the Machine.

Cannot you see that it is we that are dying, and that down here the only thing that really lives is the Machine?

We created the Machine, to do our will, but we cannot make it do our will now. It has robbed us of the sense of space and of the sense of touch, it has blurred every human relation and narrowed down love to a carnal act, it has paralysed our bodies and our wills, and now it compels us to worship it. The Machine develops—but not on our lines. The Machine proceeds—but not to our goal. We only exist as the blood corpuscles that course through its arteries, and if it could work without us, it would let us die. Oh, I have no remedy—or, at least, only one—to tell men again and again that I have seen the hills of Wessex as Ælfrid saw them when he overthrew the Danes.

14. “How To Think Slowly” by Amrita Singh.

An essay about cognitive biases and hacks for getting around them in everyday situations.

Perhaps you only shout at your child when they do something atrocious. You notice that they behave better the next day. Don’t take that as an affirmation that shouting is good—it could be regression to the mean!

If you learn of a miracle cure for a serious disease, ask if there was a placebo group to control for regression to the mean (the sickest people in a group will appear to get better over time, just like the heaviest people appear to lose weight over time).

When you move to a new city, sample ten restaurants and take your guest to the best one, be prepared for disappointment—you probably caught them on an unusually good day. They might regress to the mean when you visit them again.

15. “Contemplative Wisdom for Superalignment” by Adam Elwood.

How using the free energy principle to formalize buddhist insights could allow us to overcome many issues with alignment and build intrinsically aligned AI systems

16. “How to have faith in humanity” by Aaron Zinger.

A dose of gratitude and optimism toward civilization, via charts, old poetry, and a personal anecdote.

My first time getting an MRI was a spiritual experience.

I’m sure repetition will dull the luster, but coming home afterwards I was positively euphoric. My appointment was in the evening in Manhattan, so at my spouse’s suggestion we made a little date night out of it. “Dinner and a show,” I joked, “where the show is my brain.” But it turned out she’d come up with an actual show idea. As it happened, right next to the clinic was an installation of Bruce Munro’s Field of Light.

From above, Field of Light is just that—an irregular glow scattered across several blocks, slowly shifting color. It was originally placed in the shadow of the Uluru sandstone monolith in Australia. Below glowing skyscrapers, of course, it hits a little differently.

17. “Spirits and the incompleteness of physics” by Mechanics of Aesthetics.

A theoretical physicist describes why physics will remain forever incomplete, and what this opens the door to.

Take a box with a few hundred atoms at low temperature, perfectly isolated from the environment. Low temperature means we’re in the regime of understood physics. Imagine we can measure every atom’s position and velocity precisely. We leave the box alone for a long time, then ask: where are all the atoms now?

With unlimited computing power, our best theories should handle this easily. But they can’t. There’s a finite time horizon beyond which no physical theory in our possession can predict the atoms’ locations—even at low energies, and even with a galaxy of Dyson spheres powering our GPUs.

18. “Why Are We Conscious? A Social Scientific Explanation” by Chris Bidner and Patrick Francois.

A paper proposing a formal, evolutionary theory of consciousness based on how it arose to aid prosocial interaction.

19. “Flow, Benzaiten, Dreams, Labyrinths” by Galactic Beyond.

Tersely explores how most of the universe can be characterized by flow, how flows emerge from tensions/contradictions, and how humanity is characterized by the tension between our dreams and the real world.

The core tension, is that our imaginations are infinitely powerful, but manifesting what we imagine is difficult at best and impossible at worst. To dream of the colonization of mars, or the exploration of the deep sea, is only the beginning of the struggle to bring the dream to life. Influence is anything that can make a human struggle in the service of a dream. Influence is potential energy, and human struggle is kinetic energy.

20. “You, Me and the AI Genie” by Wabi Sabi.

Probing the emotional roots of my and many others’ resentment towards GenAI.

I hate generative AI.

I hate everything about it. I experience its existence as a personal insult and spend a little of each day wishing it had never been invented. I hate that the genie is never going back in the bottle - bar some kind of civilisational reset that some of our global leaders seem hellbent on accelerating - and that even if it did, I’d be stuck with the knowledge that I lived in the kind of universe that could contain something like that genie.

I hate that reasonable people disagree about whether the genie is sentient or not, or whether it has motivations, or thinks, or uses reason in the proper sense of the world, or has a mental model of the world, or can be described as an agent, or possesses consciousness. I hate that this very post is going to be fed to the genie…

21. “Building Middlementum” by Gilad Seckler.

Research shows that motivation tends to follow a U-shaped curve through the life of a project; these are some strategies to fight the dip.

In the long shadow of the replication crisis, it’s dangerous to take any one study as gospel. But this one feels quite common-sensical —a formalization of what, I think, most of us have experienced firsthand: Enthusiasm is naturally highest when you’re either gripped by novelty or can make a big push toward completion. Tedium, avoidance, and indecision, by contrast, are most likely to set in when you are slogging ahead with no end in sight.

22. “How does any of this mean?” by Alexandra Taylor.

How meaning emerges not only from literal content but from the interplay between elements of form.

All forms of communication involve limitations, whether they are self-imposed or inherent to the medium.

It’s easy to fixate on the logic of what we want to say—the core message, the right angle, the ideal frame—and forget to consider how we say it—the format, tone, rhythm, images, and voice. But the strength of these elements is often how the meaning lands.

The audience can feel when something has been made with care (what Robert Frost calls “the pleasure of taking pains”), and this care helps to create trust.

23. “A pragmatic user’s guide to, uh, chi’" by @utotranslucence.

A theory of chi with no wild epistemic leaps required.

So, one part of ‘energy’ is the experience of having your nervous system get influenced by another person’s nervous system without having the conscious perception of what changed to make your nervous system change. This makes it feel like the change was ‘magical’ or ‘spooky action at a distance’, but I’m pretty confident that people can, with training, learn to perceive, if not from a distance then at least with touch, all the signals that their body is already subconsciously reacting to, and with enough perceptive skill there is no ‘unexplained influence’ or changes in your nervous system that can’t be explained by something happening in your body or mind or in what you are able to perceive of someone else’s body or mind.

24. “What Business Can Learn From Sports” by Robert Gentle.

What corporate recruiters can learn from professional sports.

Similar influences can be found in sport. For example, golf and tennis require a huge investment in equipment, time and coaching. So, professional golfers and tennis players are more likely to be middle-class than working-class, and white rather than black. This contrasts with soccer, where all you need is a ball and a rough patch of ground; or marathon running, which only requires the great outdoors. This is why poorer African countries, with their lack of modern sports infrastructure, typically field runners and soccer teams at the Olympic Games rather than swimmers, gymnasts or cyclists.

25. “Mind Uploading - Is That Really You?” by Jack Massa.

The story behind the story of a science fiction tale, exploring speculations about whole-brain emulation.

Still, given an indefinite amount of time, simulated experiences, no matter how exciting and exotic, are likely to pall. Imagine sitting on your couch alone forever, just watching TV and playing video games.

I do think alone may be the key here. Loneliness might be the great downside of digital immortality.

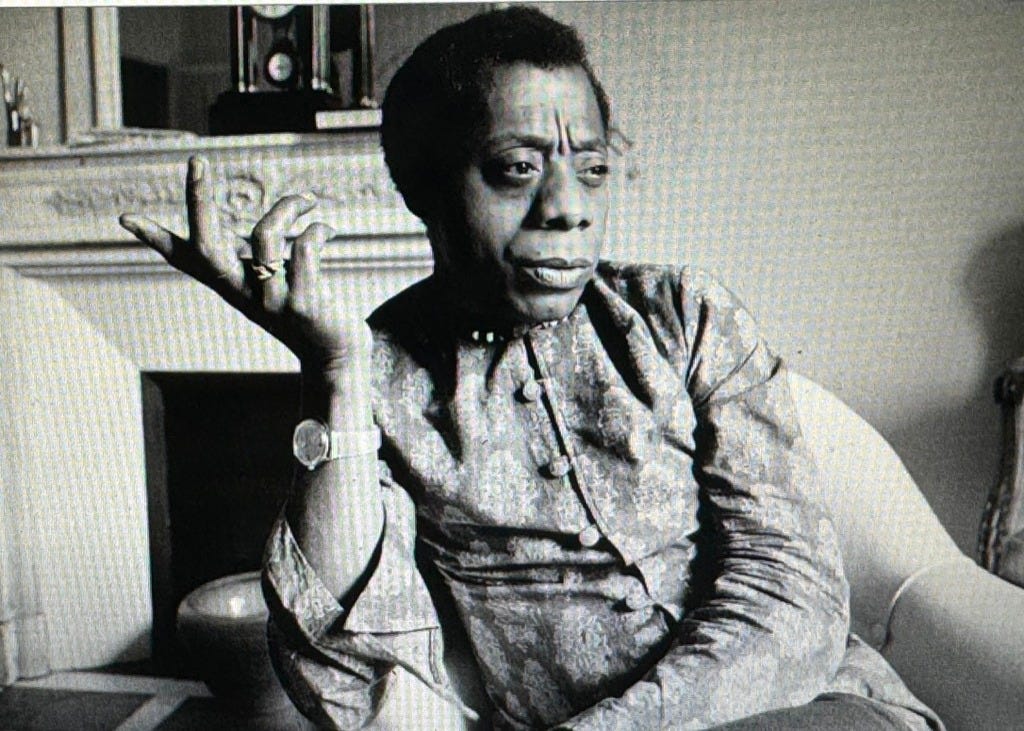

26. “The Oath” by Luis Miron.

He stopped responding to news clips or arguments online. Instead, he read: Valeria Luiselli, James Baldwin, even Malcolm X. Not because they told him what to think—but because they reminded him he wasn’t imagining it. His first love was James Baldwin, whom he captured in a lost photo, sitting desk-by-desk with a photographer friend, who apparently took multiple photos in New Orleans.

27. “AI(,) Art(,) and Science” by David Wych.

While reading a recent New Yorker piece about AI/ML and Art by the science fiction writer Ted Chiang I was pleasantly surprised by his definition:

Art is something that results from making a lot of choices.

I like this definition of art. It has the benefit of being both easy to understand and no less effective in generalization.

Though this definition works nicely as a heuristic, it doesn’t map cleanly on to my experience of making art. What art I’ve made that’s felt even the slightest bit personal and transcendent was made in a flow state: not quite devoid of choice but unconcerned with it; more akin to surrender than willful effort.

28. “I AM CONSCIOUS, THEREFORE I AM: Thoughts On Why We Are Conscious” by Steven Sangapore.

As complexity in organisms increases, so does the need for emotion and subjective experience as mediators between the extrinsic domain of facts and events of the material world and the inner, subjective world of value judgements and organism behavior.

Somewhere along the scientific journey this juggernaut of discovery had decided to essentially ignore the most fundamental feature of our existence: subjective experience. Science presses on probing deeper into extrinsic reality while simultaneously adopting a willfully blind attitude toward the intrinsic world of consciousness. This blindness makes science not only incomplete, but wildly incomplete. Even the cherished idea of developing a “theory of everything” would hardly scratch the surface of including everything there is to be understood about the universe.

Thank you for sharing my essay! Excited to read some of these.

This looks like a great collection. Thanks for sharing, Erik!