Literacy lag: We start reading too late

Teaching (very) early reading: Part 5

What is literacy lag?

Children today grow up under a tyrannical asymmetry: exposed to screens from a young age, only much later do we deign to teach them how to read. So the competition between screens vs. reading for the mind of the American child is fundamentally unfair. This is literacy lag.

Despite what many education experts would have you believe, literacy lag is not some natural or biological law. Children can learn to read very early, even in the 2-4 age range, but our schools simply take their sweet time teaching the skill; usually it is only in the 7-8 age range that independent reading for pleasure becomes a viable alternative to screens (and often more like 9-10, as that’s when the “4th grade slump” occurs, based on kids switching from academic exercises to actually reading to learn). Lacking other options, children must get their pre-literate media consumption from screens, which they form a lifelong habitual and emotional attachment to.

Nowadays, by the age of 6, about 62% of children in the US have a personal tablet of their own, and children in the 5-8 age range experience about 3.5 hours of screen time a day (increasingly short-form content, like YouTube Shorts and TikTok).

I understand why. Parenting is hard, if just because filling a kid’s days and hours and minutes and seconds is, with each tick of the clock, itself hard. However, I noticed something remarkable from teaching my own child to read. Even as a rowdy “threenager,” he got noticeably easier as literacy kicked in. His moments of curling up with a book became moments of rejuvenating parental calm. And I think this is the exact same effect sought by parents giving their kids tablets at that age.

Acting up in the car? Have you read this book? Screaming wildly because you’re somehow both overtired and undertired? Please go read a book and chill out!

This is because reading and tablets are directly competitive media for a child’s time.1 So while independent reading requires about a year of upfront work, and takes anywhere from 10-30 minutes a day, after that early reading feels a lot like owning a tablet (and while reading is no panacea, neither are tablets).

The cultural reliance on screen-based media is not because parents don’t care. I think the typical story of a new American parent, a quarter of the way through this 21st century of ours, goes like this: initially, they do care about media exposure, and often read to their baby and young toddler regularly. This continues for 2-3 years. However, eventually the inconvenience of reading requiring two people pressures parents to switch to screens.2 The category of “not playing, and not doing a directed or already set up activity, but just quietly consuming media” is simply too large and deep for parents to fill just by reading books aloud. In fact, not providing screens can feel impoverishing, because young children have an endless appetite for new information.

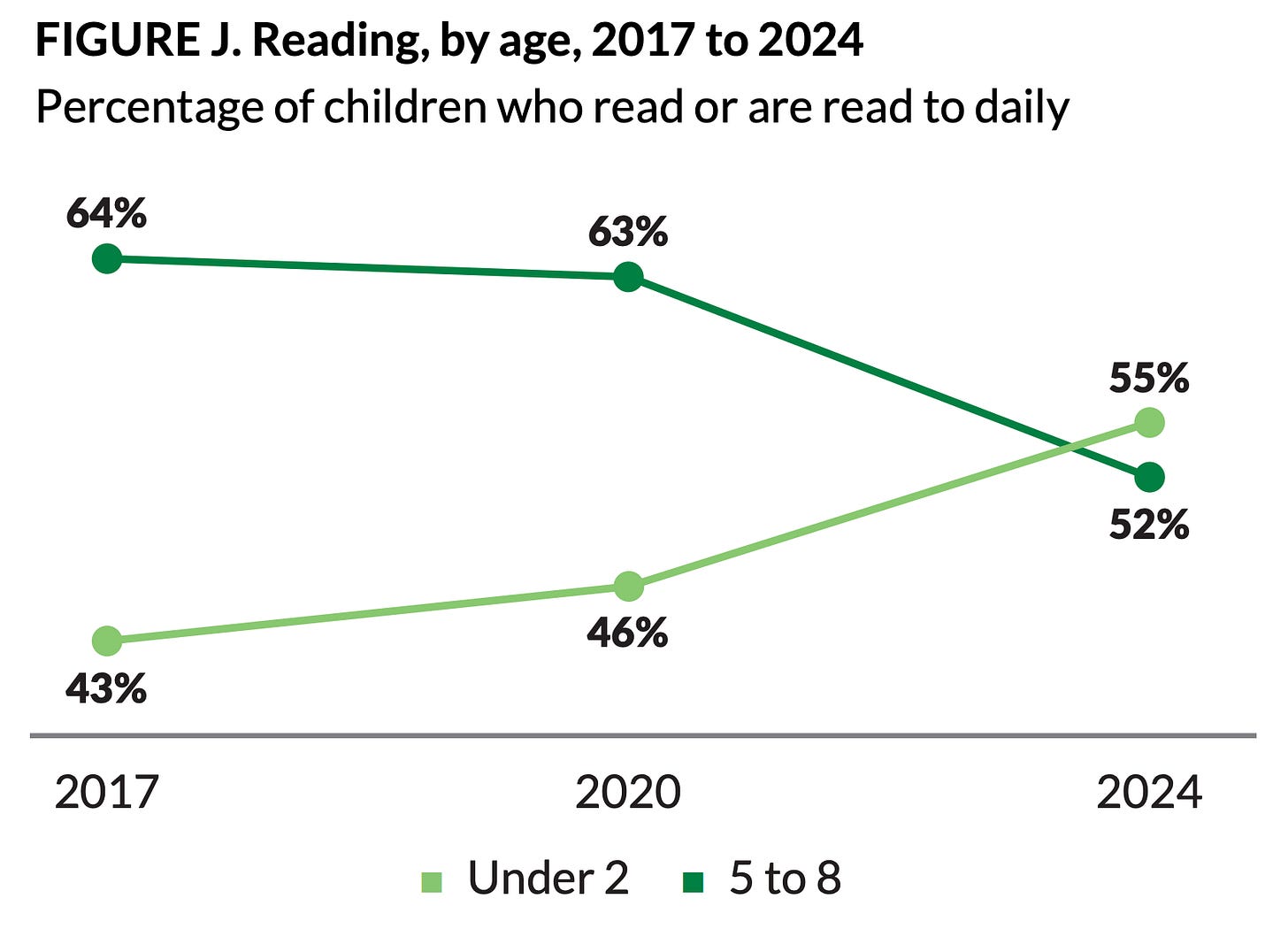

Survey data support this story: parental reading to 2-year-olds has actually increased significantly since 2017, but kids in the 5-8 range get exposed to reading much less. Incredibly, the average 2-year-old is now more likely to be exposed to reading than the average 8-year-old!

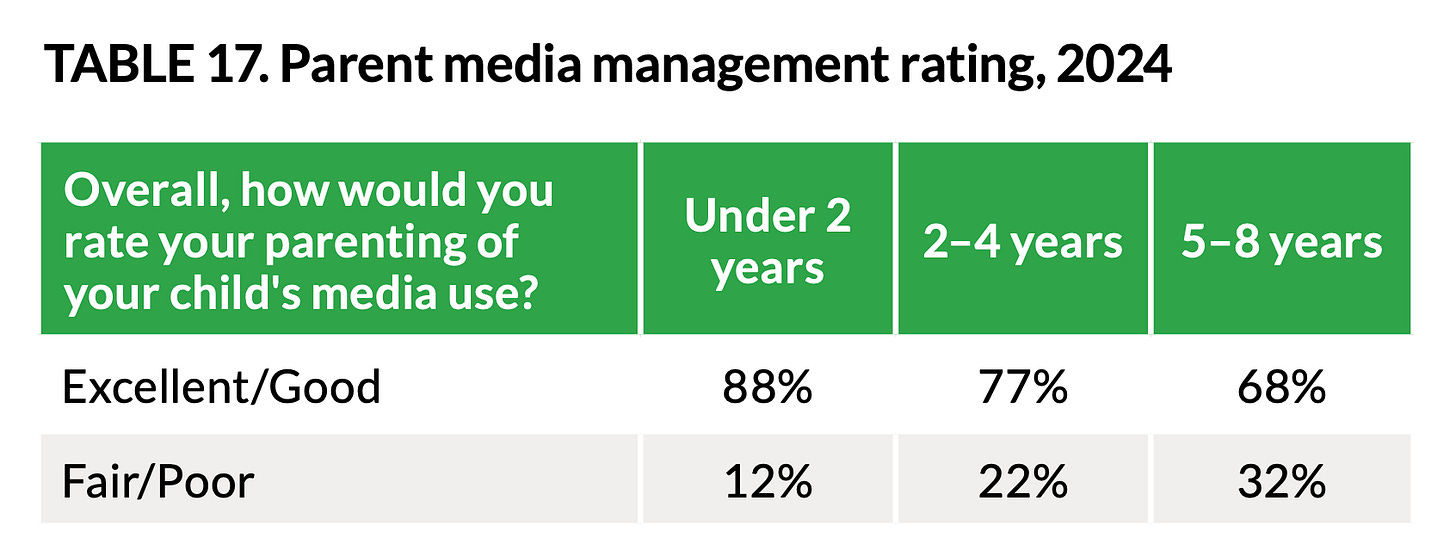

Self reports also fit this story: parents acknowledge they do a better job at media use when it comes to their 2-year-olds compared to their 8-year-olds, and the drop-off is prominent during the literacy lag.

So despite American parents’ best efforts to prioritize reading over screen usage for their toddlers, due to our enforced literacy lag, being a daily reader is a trait easily lost early on, and then must be actively regained rather than maintained.

Once lost, reading often doesn’t recover. Even when surveyed from a skeptical perspective, reading is, almost everywhere, in decline.3 This is supported by testimonials from teachers (numerous op-eds, online threads, the entire horror show that is the /r/Teachers subreddit), as well as the shrinking of assigned readings into fragmented excerpts rather than actual books. At this point, only 17% of educators primarily assign whole books (i.e., the complete thoughts of authors), and some more pessimistic estimates put this percentage much lower, like how English Language Arts curricula based on reading whole books are implemented in only about 5% of classrooms. On top of all this, actual objective reading scores are now the lowest in decades.

I think literacy lag is a larger contributor to this than anyone suspects; we increasingly live in a supersensorium, so it matters that literature is fighting for attention and relevancy with one hand tied behind its back for the first 8 years of life.

So then…

Why are education experts so against early reading?

In a piece that could have been addressed to me personally, last month the LA Times published:

Hey!

While it doesn’t actually reference my growing guide on early reading (we’re doing early math next, so stay tuned), what this piece in the LA Times reveals is how traditional education experts have tied themselves up in knots over this question. E.g., the LA Times piece contains statements like this:

“Can a child learn individual letters at 2½ or 3? Sure. But is it developmentally appropriate? Absolutely not,” said Susan Neuman, a professor of childhood and literacy education at New York University.

Now, to give you a sense of scale here, Susan Neuman is a highly-cited researcher and, decades ago, worked on implementing No Child Left Behind. She also appears to think it’s developmentally inappropriate to teach a 3-year-old what an “A” is. And this sort of strange infantilization appears to be widespread.

“When we talk about early literacy, we don’t usually think about physical development, but it’s one of the key components,” said Stacy Benge, author of The Whole Child Alphabet: How Young Children Actually Develop Literacy. Crawling, reaching across the floor to grab a block, and even developing a sense of balance are all key to reading and writing, she said. “In preschool we rob them of those experiences in favor of direct instructions,” said Benge.

Yet is crawling across the floor to grab a block really the normal developmental purview of preschool? Kids in preschool are ambulatory. Bipedal. Possessing opposable thumbs, they can indeed pick up blocks. Preschool usually starts around the 3-4 age range, often requiring the child to be potty-trained. Preschoolers are entire little people with big personalities. Moreover, by necessity preschool is still mostly (although not entirely) play-based in terms of the learning and activities, if only because there is zero chance a room of 3-year-olds could sit at desks for hours on end.

This all seems off. Surely, there must be some robust science behind this fear of teaching reading too early?4 It turns out, no. It’s just driven by…

Neuromyths about early reading.

The LA Times piece leans heavily on the opinions of cognitive neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf, who is well-known for her work in education and the science of reading:

For the vast majority of children, research suggests that ages 5 to 7 are the prime time to teach reading, said Maryanne Wolf, director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners and Social Justice at UCLA.

“I even think that it’s really wrong for parents to ever try to push reading before 5,” because it is “forcing connections that don’t need to be forced,” said Wolf.

Reading words off a page is a complex activity that requires the brain to put together multiple areas responsible for different aspects of language and thought. It requires a level of physical brain development called mylenation [sic] — the growth of fatty sheaths that wrap around nerve cells, insulating them and allowing information to travel more quickly and efficiently through the brain. This process hasn’t developed sufficiently until between 5 and 7 years old, and some boys tend to develop the ability later than girls.

If she had a magic wand, Wolf said she would require all schools in the U.S. to wait until at least age 6.

That’s a strong opinion! I wanted to know the scientific evidence, so I dusted off Maryanne Wolf’s popular 2007 book, Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain from my library. The section “When Should a Young Child Begin to Read?” makes identical arguments to those that Wolf makes in the LA Times article, wherein myelination is cited as a reason to delay teaching reading. Wolf writes that:

The behavioral neurologist Norman Geschwind suggested that for most children myelination of the angular gyrus region was not sufficiently developed till school age, that is, between 5 and 7 years.... Geschwind’s conclusions about when a child's brain is sufficiently developed to read receive support from a variety of cross-linguistic findings.

Yet while Geschwind’s highly-cited paper is a classic of neuroscience, it is also 60 years old, highly dense, notoriously difficult to read, and ultimately contains mere anatomical observations and speculations, mostly about things far beyond these subjects. Nor do I find, after searching within it, a clear statement of this hypothesis as described. E.g., in one part, Geschwind seems to speculate that the angular gyrus being underdeveloped is the cause of dyslexia, but this is not the same as saying that finished development is a requisite for reading in normal children. Instead, there is a part where he speculates that reading can be acquired after the ability to name colors, but naming colors can often occur quite early, and varies widely (e.g., plenty, but not all, toddlers can name colors well).

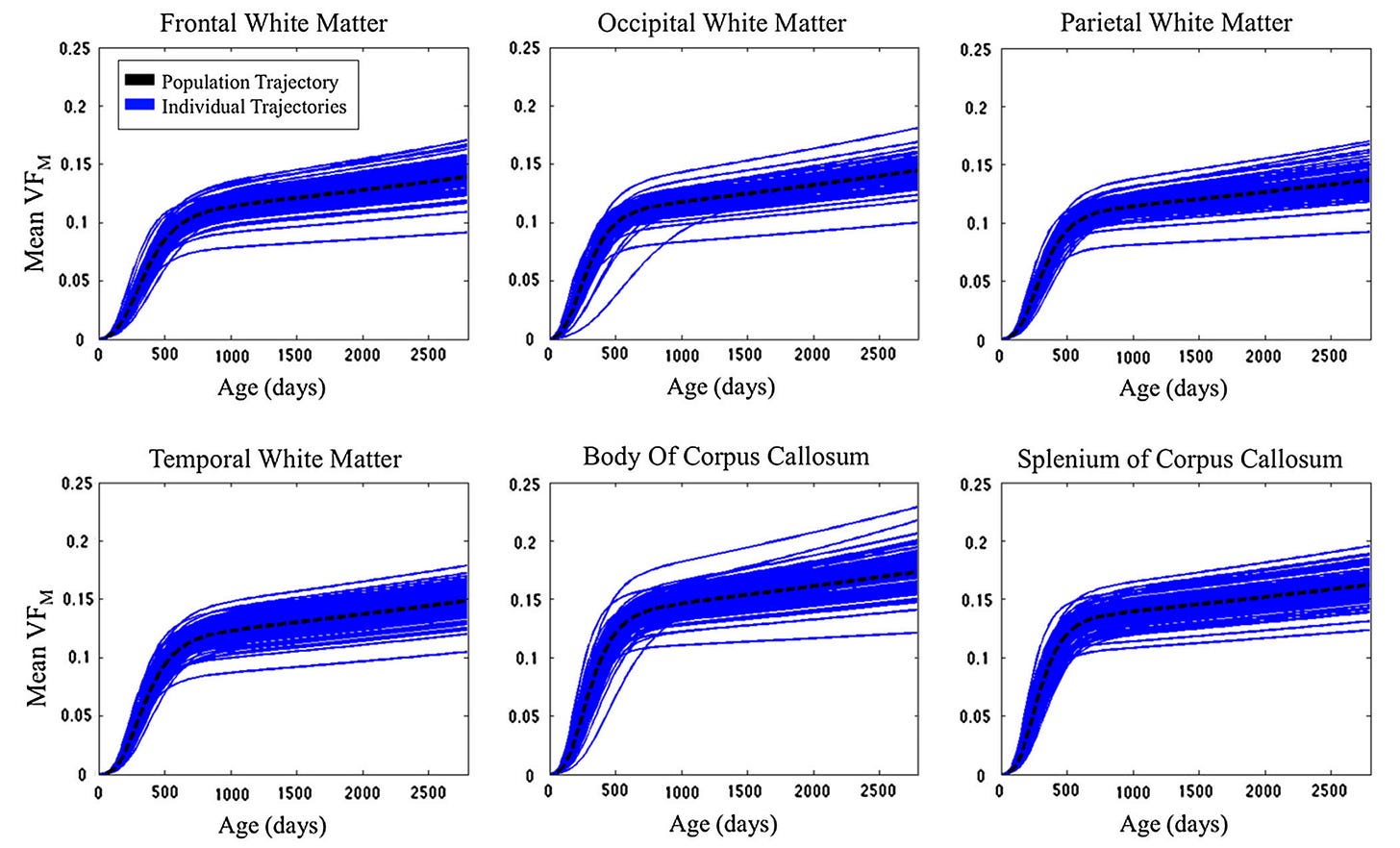

Regardless of whatever Geschwind actually believed, this 60-year-old paper would be a very old peg to hang a hat on. Modern studies don’t show myelination as a binary switch: e.g., temporal and angular gyri exhibit "rapid growth” between 1-2 years old, likely driven by myelination, and there is “high individual developmental variation” of myelination in general in the 2-5 age range, and also myelination, since it’s an anatomical expression of brain development, is responsive to learning itself.

Overall, theories positing cognitive closure based on myelin development (especially after the 1-2 age range) are not well-supported. This is because, brain-wide, the ramp up in myelination occurs mostly within the first ~500 days of life (before 2 years old), leveling off afterward to a gentle slope that can last for decades in some areas.

So then, what about the “cross-linguistic findings” that supposedly provide empirical support for a ban on early reading? Wolf writes in Proust and the Squid that:

The British reading researcher Usha Goswami drew my attention to a fascinating cross-language study by her group. They found across three different languages that European children who were asked to begin to learn to read at age five did less well than those who began to learn at age seven. What we conclude from this research is that the many efforts to teach a child to read before four or five years of age are biologically precipitate and potentially counterproductive for many children.

But the main takeaway from Goswami herself appears to be the opposite. Here is Goswami describing, in 2003, her work of the time:

Children across Europe begin learning to read at a variety of ages, with children in England being taught relatively early (from age four) and children in Scandinavian countries being taught relatively late (at around age seven). Despite their early start, English-speaking children find the going tough….

The main reason that English children lag behind their European peers in acquiring proficient reading skills is that the English language presents them with a far more difficult learning problem.

In other words, German and Finnish and so on are just easier languages to master than English, and phonics works more directly within them, so of course the kids in those countries have an easier time—and they start school later, too. As Goswami explicitly says, “it is the spelling system and not the child that causes the learning problem….”5

So no, teaching children to read at four or five, or even younger, is not “biologically precipitate.” It is also contradicted by the simple fact that…

Children used to learn to read at ages 2-4!

Here is from the 1660 classic A New Discovery of the Old Art of Teaching Schoole by Charles Hoole, an English educator who himself was a popular education expert of his day (running a grammar school and writing monographs and books).

I observe that betwixt three and four years of age a childe hath great propensity to peep into a book, and then is the most seasonable time (if conveniences may be had otherwise) for him to begin to learn; and though perhaps then he cannot speak so very distinctly, yet the often pronounciation of his letters, will be a means to help his speech…

And his writings about toddler literacy (which, by the way, are based in phonics), contain anecdotes of parents teaching their children letters at age 2.5, and of children being able to read the dense and complex language of the Bible shortly after the age of 4. As across the pond, so here too. Rewind time to observe the early Puritans of America, and you would have found it common for mothers to teach their children earlier than we do now, using hornbooks and primers (it was Massachusetts law that parents had to teach their children to read).

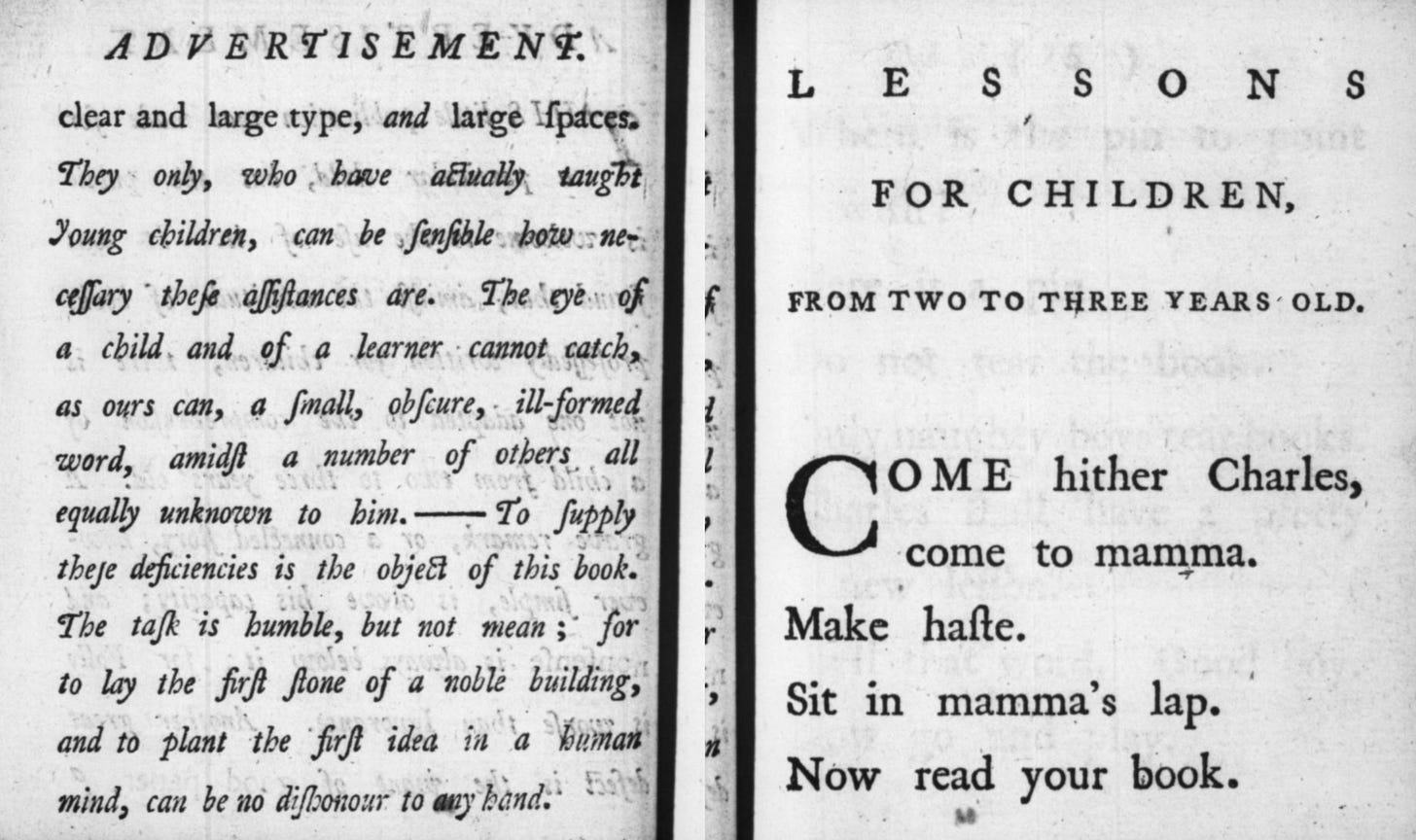

Perhaps the most famous case of teaching very early reading, and the enduring popularity of the act, comes from Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825), who was a well-known essayist and poet and educator of her day, and wrote primers aimed at children under the instruction of their governess or mother. These primers “provided a model for more than a century.” English Professor William McCarthy, who wrote a biography of Anna Laetitia Barbauld, noted that her primers…

were immensely influential in their time; they were reprinted throughout the nineteenth century in England and the United States, and their effect on nineteenth- and early twentieth-century middle-class people, who learned to read from them, is incalculable.

These “immensely influential” primers possess very revealing titles.

Lessons for Children of 2 to 3 Years Old (1778)

Lessons for Children of 3 Years Old, Part I and Part II (1778)

Lessons for Children of 3 to 4 Years Old (1779).

Yup, that’s right! Some of the most famous and successful primers ever were explicitly designed for children in the 2-4 age range. Anna Barbauld wrote it so she could teach her nephew Charles how to read, and those years track Charles’ age himself—he really was 4 in 1779.

Originally printed “sized to fit a child’s hand,” these primers contain what would be considered today wildly advanced, almost unbelievable, prose for the 2-4 age range. Even just perusing the first volume I find irregular vowels and long sentences and other complexities; things more associated with, realistically, a modern 2nd grade level (assuming a good student, too). And so, even given an extra year or two as advantage (as admittedly, some of the same era thought Barbauld’s books were titled presumptively, and recommended them instead for the 4-5 age range), there is probably a vanishingly small number of kids in the entire modern world who’d currently be Charles’ literary equals, and could read an updated version of this primer.6

The past, as they say, is a foreign country. Education practices, particularly the European tradition of “aristocratic tutoring,” were quite different. Back in 1869, Charlotte Mary Yonge wrote of Barbauld’s hero “little Charles” that the primers about him were particularly influential in the upper-class and aristocracy:

Probably three fourths of the gentry of the last three generations have learnt to read by his assistance.7

Perhaps it’s a mirror to our own age, and early reading becoming reserved for “gentry” is what modern education experts actually fear, deep down. Their concerns are about equity, grades, and whether it’s okay to “push kids into the academic rat race.” I’m not dismissing such concerns, nor saying that debate is easily solvable. Rather, my point is that there’s an entire dimension to reading that’s been seemingly forgotten: in the end, reading isn’t about grades or test scores. It’s about how kids spend their time. That’s what matters. In some ways, it matters more than anything that ever happens in schools. And right now, literacy is losing an unfair race.

We appear to be entering a topsy-turvy world, where the future is here, just not distributed along the socioeconomic gradient you’d expect. It’s a world in which it is a privilege to grow up not with, but free of, the latest technology. And I’ve come to believe that learning to read, as early as possible, is a form of that freedom.

Besides, Barbauld’s introduction to her primers ends with the appropriate rejoinder to any gatekeeping of reading, by age or otherwise:

For to lay the first stone of a noble building, and to plant the first idea in a human mind, can be no dishonor to any hand.

If you want to check out my own guide for teaching early reading (aimed at getting kids reading for pleasure), see parts 1, 2, 3 and 4. I’m putting them all together into an updated monograph (coming soon).

That TV competes with reading has been called the “displacement hypothesis” in the education literature. It’s pretty obvious that the effect is even stronger for tablets. While literacy lag existed decades ago, it was less impactful, because the availability for entertainment was more limited and not personalized (e.g., Saturday morning cartoons in the living room vs. algorithmically-fine-tuned infinite Cocomelon on the go).

Admittedly, this dichotomy of “screen time” vs. reading is a simplification, because “screen time” is a big tent. Beautiful animated movies are screen time. Whale documentaries are screen time. Educational apps are screen time. But in rarer studies that look specifically at things like reading for pleasure, it’s clear that using screens for personal entertainment (like the tablet usage I’m discussing here) is usually negatively correlated to [pick your trait or outcome].

The naysaying that reading is not in decline comes from education experts arguing that labels like “proficiency” on surveys represent a higher bar than people think, and that not being proficient doesn’t technically mean illiterate. Which is something, I suppose.

Shout out to Theresa Roberts, the only education expert quoted in the LA Times piece going against the majority opinion.

But there are also experts who say letter sounds should be taught to 3-year-olds in preschool. “Children at age 3 are very capable,” said Theresa Roberts, a former Sacramento State child development professor who researches early childhood reading.

And it doesn’t have to be a chore, she said. Her research found that 3- and 4-year-olds were “highly engaged” during 15-minute phonics lessons, and they were better prepared in kindergarten.

Wolf does mention that orthographic regularity is a confound in a later 2018 piece, but still draws the same conclusion from the research. Meanwhile, in a 2006 review written by Goswami herself and published in Nature Reviews Neuroscience called “Neuroscience and education: from research to practice?” Goswami doesn’t mention a biologically-based critical period for learning to read. Instead, using the example of synaptogenesis, she refers to ideas around such critical periods as “myths.”

The critical period myth suggests that the child’s brain will not work properly if it does not receive the right amount of stimulation at the right time… These neuromyths need to be eliminated.

It’s worth noting that Anna Barbauld’s primers are beautifully written. Constructed as a one-sided dialogue (a “chit chat”) with Charles, Barbauld dispenses wisdom about the natural world, about plants, animals, money, pets, hurts, geology, astronomy, morality and mortality. In this, it is vastly superior to contemporary early readers: it is written from within a child’s umwelt, which (and this is Barbauld’s true literary innovation) occurs via linguistic pointers from parents to things of the child’s daily world (this hasn’t changed much, e.g., the first volume ends at Charles’ bedtime). Barbauld may have also originated the use of reader-friendly large font, with extra white space, designed to go easy on toddler eyes (still a huge problem in early reading material, hundreds of years later).

Another thought - the persistent absolute belief that neuroscience understands the mind is disturbing. We can learn a lot from scans, but making categorical statements about human behavior based on myelination is several bridges too far.

I think it's partly about what's feasible in the home vs the classroom in the current American system. I've taught 3-6yos in Asia for many years now (to be reading Hop-on-Pop-level texts independently by 6) and there are many kids who just need strong phonics and appropriate material to set off on their own around 4-5. But there are others who aren't capable even at 6 of reliably reading CVC words. A lot of education systems (and teachers) have decided that the class should move at the pace of the slowest student, or the slowest third. Others simply don't have the resources to teach multiple levels in the same room. Unfortunately a lot of people seem to have decided that rather than trying to solve these probably solvable problems we should just give up.

Teachers also tend to be fixated on writing, probably because it's much easier to assess, and there is a developmental lag between what a child can read and what they're physically capable of writing. Many teachers are uncomfortable with teaching a child to read words they can't be made to write. In general receptive skills are undervalued relative to productive skills in early education and lower elementary, and that has all sorts of unfortunate downstream effects