Our Overfitted Century

Cultural stagnation is because we're stuck in-distribution

“Culture is stuck? I’ve heard this one before.”

You haven’t heard this one, but I see why you’d think that.

There’s no better marker of culture’s unoriginality than everyone talking about culture’s unoriginality.

In fact, I don’t fully trust this opening to be original at this point!

Yes, this is technically one of many articles of late (and for years now) speculating about if, and why, our culture has stagnated. As The New Republic phrased it:

Grousing about the state of culture… has become something of a specialty in recent years for the nation’s critics.

But even the author of that quote thinks there’s a real problem underneath all the grousing. Certainly, anyone who’s shown up at a movie theater in the last decade is tired of the sequels and prequels and remakes and spinoffs.

My favorite recent piece on our cultural stagnation is Adam Mastroianni’s “The Decline of Deviance.” Mastroianni points out that complaints about cultural stagnation (despite already feeling old and worn) are actually pretty new:

I’ve spent a long time studying people’s complaints from the past, and while I’ve seen plenty of gripes about how culture has become stupid, I haven’t seen many people complaining that it’s become stagnant. In fact, you can find lots of people in the past worrying that there’s too much new stuff.

He hypothesizes cultural stagnation is driven by a decline of deviancy:

[People are] also less likely to smoke, have sex, or get in a fight, less likely to abuse painkillers, and less likely to do meth, ecstasy, hallucinogens, inhalants, and heroin. (Don’t kids vape now instead of smoking? No: vaping also declined from 2015 to 2023.) Weed peaked in the late 90s, when almost 50% of high schoolers reported that they had toked up at least once. Now that number is down to 30%. Kids these days are even more likely to use their seatbelts.

Mastroianni’s explanation is that the weirdos and freaks who actually move culture forward with new music and books and movies and genres of art have disappeared, potentially because life is just so comfortable and high-quality now that it nudges people against risk-taking.

Meanwhile, Chris Dalla Riva, writing at Slow Boring, says that (one major) hidden cause of cultural stagnation is intellectual property rights being too long and restrictive. If such rights were shorter and less restrictive, then there wouldn’t be as much incentive to exploit rather than produce.

In other accounts, corporate monopolies or soulless financing is the problem. Andrew deWaard, author of the 2024 book Derivative Media, says the source of stagnation is the move into cultural production by big business.

We are drowning in reboots, repurposed songs, sequels and franchises because of the growing influence of financial firms in the cultural industries. Over time, the media landscape has been consolidated and monopolized by a handful of companies. There are just three record companies that own the copyright to most popular music. There are only four or five studios left creating movies and TV shows. Our media is distributed through the big three tech companies. These companies are backed by financial firms that prioritize profit above all else. So, we end up with less creative risk-taking….

Or maybe it’s the internet itself?

That’s addressed in Noah Smith’s review of the just-published book Blank Space: A Cultural History of the 21st Century by David Marx (I too had planned a review of Blank Space in this context, but got soundly scooped by Smith).

Here’s Noah Smith describing Blank Space and its author:

Marx, in my opinion, is a woefully underrated thinker on culture…. Most of Blank Space is just a narration of all the important things that happened in American pop culture since the year 2000….

But David Marx’s talent as a writer is such that he can make it feel like a coherent story. In his telling, 21st century culture has been all about the internet, and the overall effect of the internet has been a trend toward bland uniformity and crass commercialism.

Personally, I felt that a lot of Blank Space’s cultural history of the 21st century was a listicle of incredibly dumb things that happened online. But that isn’t David Marx’s fault! The nature of what he’s writing about supports his thesis. An intellectual history of culture in the 21st century is forced to contain sentences like “The rising fascination with trad wives made it an obvious space for opportunists,” and they just stack on top of each other, demoralizing you.

However, as Katherine Dee pointed out, the internet undeniably is where the cultural energy is. She argues that:

If these new forms aren’t dismissed by critics, it’s because most of them don’t even register as relevant. Or maybe because they can’t even perceive them.

The social media personality is one example of a new form. Personalities like Bronze Age Pervert, Caroline Calloway, Nara Smith, mukbanger Nikocado Avocado, or even Mr. Stuck Culture himself, Paul Skallas, are themselves continuous works of expression—not quite performance art, but something like it…. The entire avatar, built across various platforms over a period of time, constitutes the art.

But even granting Dee’s point, there are still plenty of other areas stagnating, especially cultural staples with really big audiences. Are the inventions of the internet personality (as somehow distinct from the celebrity of yore) and short-form video content enough to counterbalance that?

Maybe even the term, “cultural stagnation,” isn’t quite right. As Ted Gioia points out in “Is Mid-20th Century American Culture Getting Erased?” we’re not exactly stuck in the past.

Not long ago, any short list of great American novelists would include obvious names such as John Updike, Saul Bellow, and Ralph Ellison. But nowadays I don’t hear anybody say they are reading their books.

So maybe the new stuff just… kind of sucks?

Last week in The New York Times, Sam Kriss wrote a piece about the sucky sameness of modern prose, now that so many are using the same AI “omni-writer,” with its tells and tics of things like em dashes.

Within the A.I.’s training data, the em dash is more likely to appear in texts that have been marked as well-formed, high-quality prose. A.I. works by statistics. If this punctuation mark appears with increased frequency in high-quality writing, then one way to produce your own high-quality writing is to absolutely drench it with the punctuation mark in question. So now, no matter where it’s coming from or why, millions of people recognize the em dash as a sign of zero-effort, low-quality algorithmic slop.

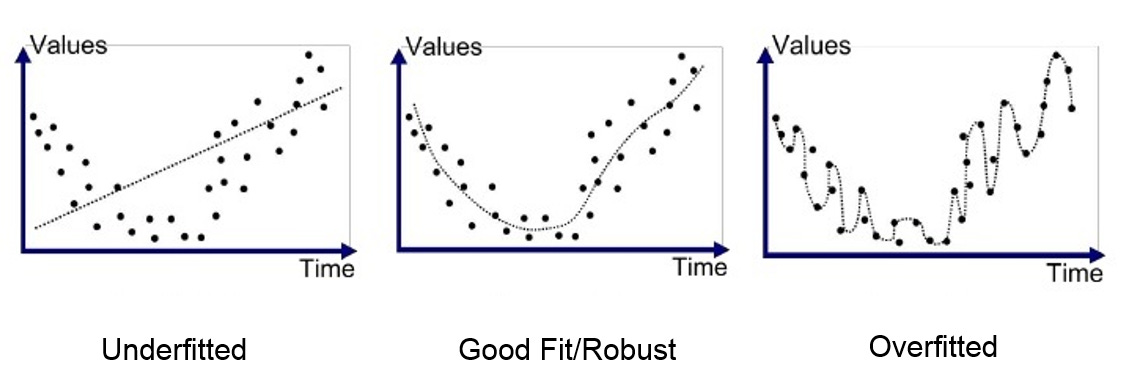

The technical term for this is “overfitting,” and it’s something A.I. does a lot.

I think overfitting is precisely the thing to be focused on here. While Kriss mentions overfitting when it comes to AI writing, I’ve thought for a long while now that AI is merely accelerating an overfitting process that started when culture began to be mass-produced in more efficient ways, from the late 20th through the 21st century.

Maybe everything is overfitted now.

“Man, someone should write a book about cultural overfitting!”

Oh, I tried. I pitched something close to the idea of this essay to the publishing industry a year and a half ago, a book proposal titled Culture Collapse.

Wouldn’t it be cool if Culture Collapse, a big nonfiction tome on this topic, mixing cultural history with neuroscience and AI, were coming out soon?1 But yeah, a couple big publishing houses rejected it and my agent and I gave up.

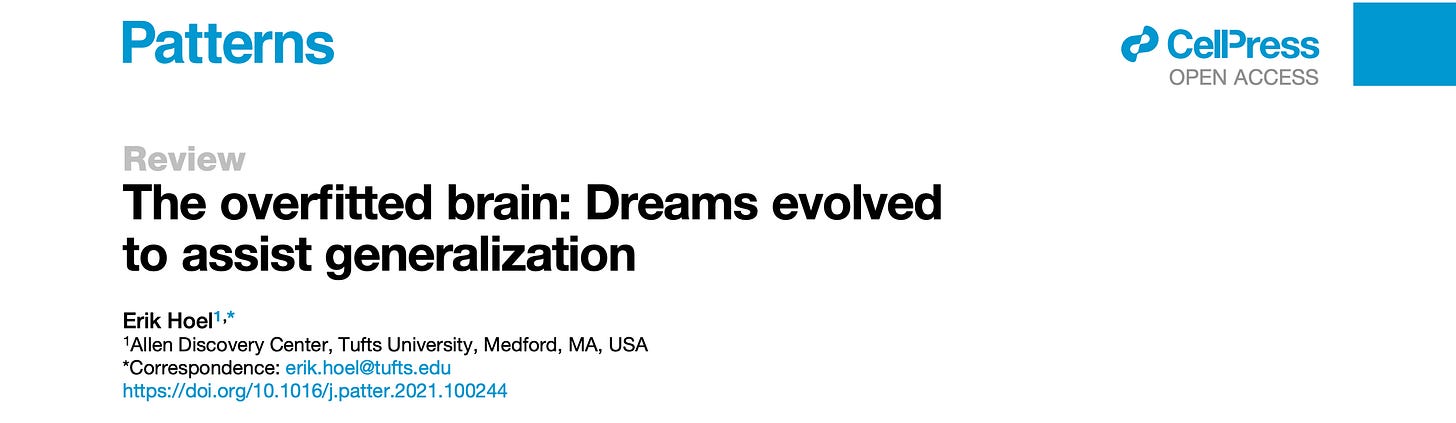

My plan was to ground the book in the neuroscience of dreaming and learning. Specifically, the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis, which I published in 2021 in Patterns.

I’ll let other scientists summarize the idea (this is from a review published simultaneously with my paper):

Hoel proposes a different role for dreams…. that dreams help to prevent overfitting. Specifically, he proposes that the purpose of dreaming is to aid generalization and robustness of learned neural representations obtained through interactive waking experience. Dreams, Hoel theorizes, are augmented samples of waking experiences that guide neural representations away from overfitting waking experiences.

Basically, during the day, your mammalian brain can’t stop learning. Your brain is just too plastic. But since you do repetitive boring daily stuff (hey, me too!), your brain starts to overfit to that stuff, as it can’t stop learning.

Enter dreams.

Dreams shake your brain away from its overfitted state and allow you to generalize once more. And they’re needed because brains can’t stop learning.

But culture can’t stop learning either.

So what if we thought of culture as a big “macroscale” global brain? Couldn’t that thing become overfitted too? In which case, culture might lose the ability to generalize, and one main sign of this would be an overall lack of creativity and decreasing variance in outputs.

Which might explain why everything suddenly looks the same.

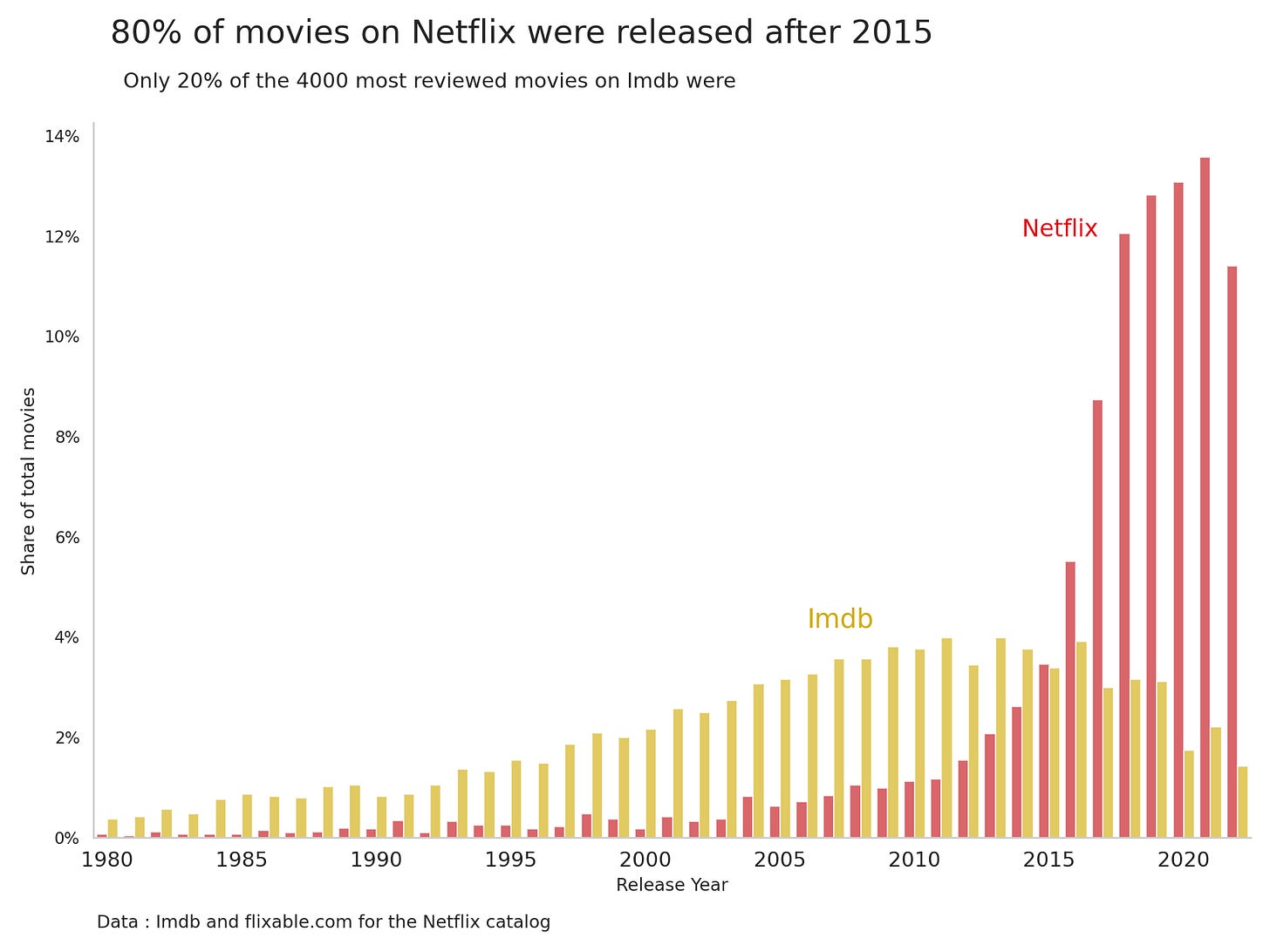

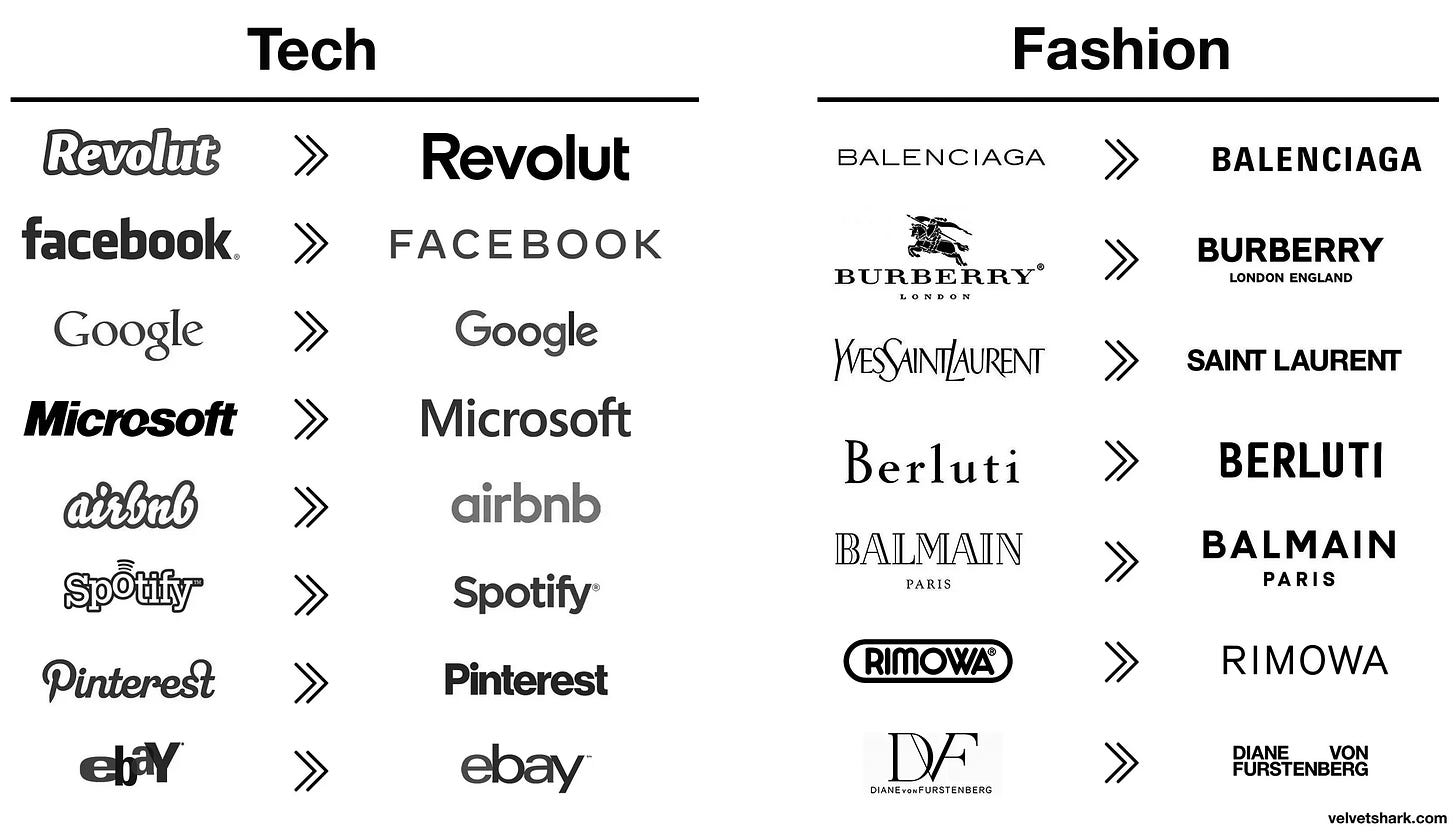

Here’s a collection of images, most from Adam Mastroianni’s “The Decline of Deviance,” showcasing cultural overfitting, ranging from brand names:

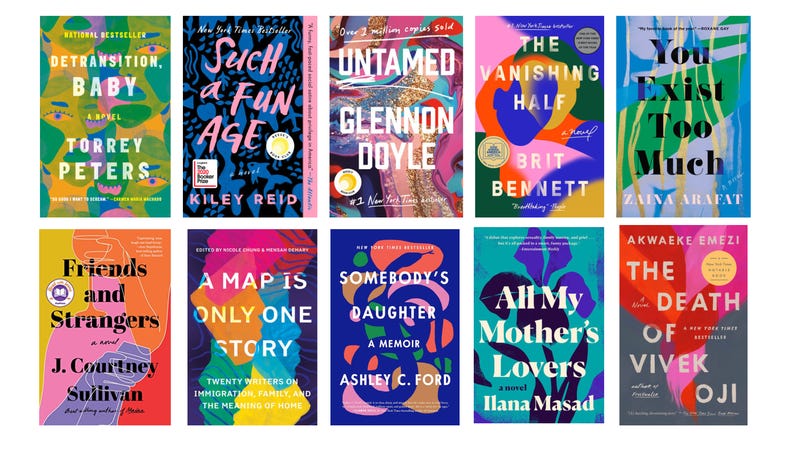

To book covers:

To thumbnails:

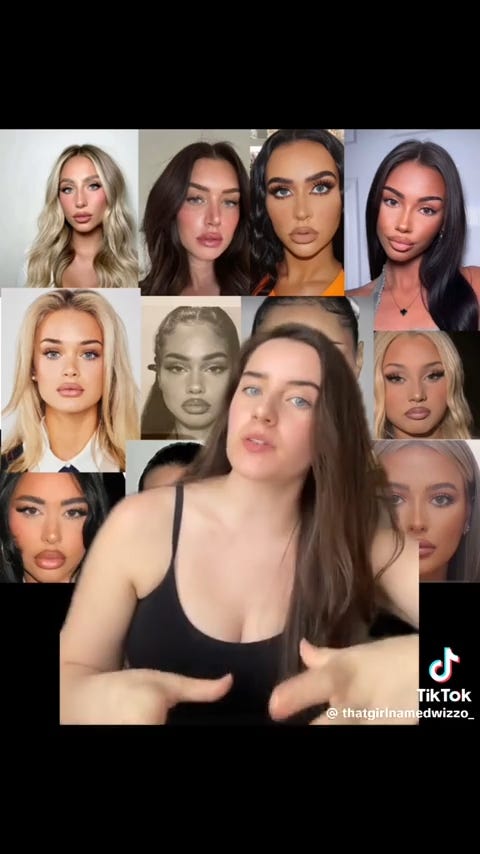

To faces:

Alex Murrell’s “The Age of Average” contains even more examples. But I don’t think “Instagram face” is just an averaging of faces. It’s more like you’ve made a copy of a copy of a copy and arrived at something overfitted to people’s concept of beauty.

Of course, you can’t prove that culture is overfitted by a handful of images (the book, ahem, would have marshaled a lot more evidence). But once you suspect overfitting in culture, it’s hard to not see it everywhere, and you start getting paranoid.

“Can we simply… turn off the overfitting?”

Nope. Overfitting is amorphous and structural and haunting us. It’s our cultural ghost.

Although note: I’m using “overfitting” broadly here, covering a swath of situations. In the book, I’d have been more specific about the analogy, and where overfitting applies and doesn’t.

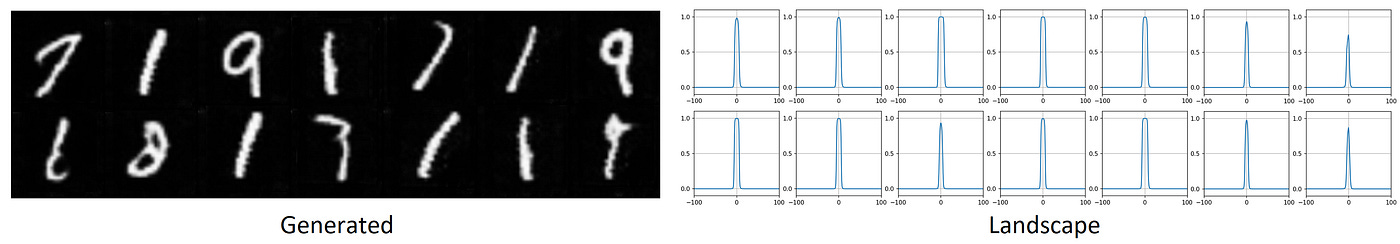

I’d probably also define the interplay between “overfitting” vs. “mode collapse” vs. “model collapse.” E.g., “mode collapse” is a failure in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which are composed of two parts: a generator (images, text, etc.) and a discriminator (judging what gets generated).

Mode collapse is when the generator starts producing highly similar and unoriginal outputs, and a major way this can happen is through overfitting by the discriminator: the discriminator gets too judgy or sensitive and the generator must become boring and repetitive to satisfy it.

An example of cultural mode collapse might be superhero franchises, driven by a discriminatory algorithm (the entire system of Big Budget franchise production) overfitting to financial and box office signals, leading to dimensionally-reduced outputs. And so on. Basically, overfitting is a common root cause of a lot of learning and generative problems, and increased efficiency can easily lead to hyper-discriminatory capabilities that, in turn, lead to overfitting.

In online culture, overfitting shows up as audience capture. In the automotive industry, it shows up as eking out every last bit of efficiency, like in the car example above. Clearly, things like wind tunnels, the consolidation of companies, and so on, conspire toward this result (and interesting concept cars in showrooms always morph back into the same old boring car).

So too with “Instagram face.” Plastic surgery has become increasingly efficient and inexpensive, so people iterate on it in attempts to be more beautiful, while at the same time, the discriminatory algorithm of views and follows and left/right swipes and so on becomes hypersensitive via extreme efficiency too, and the result of all this overfitting is The Face.

Overall, I think the switch from an editorial room with conscious human oversight to algorithmic feeds (which plenty of others pinpoint as a possible cause for cultural stagnation) likely was a major factor in the 21st century becoming overfitted. And also, again, the efficiency of financing, capital markets (and now prediction markets), and so on, all conspire toward this.

People get riled up if you use the word “capitalism” as an explanation for things, and everyone squares off for a political debate. But, while I’m mostly avoiding that debate here, I can’t help but wonder if some of the complaints about “late-stage capitalism” actually break down into something like “this system has gotten oppressively efficient and therefore overfitted, and overfitted systems suck to live in.”

Cultural overfitting connects with other things I’ve written about. In “Curious George and the Case of the Unconscious Culture” I pointed out that our culture is draining of consciousness at key decision points; more and more, our economy and society is produced unconsciously.

If I picture the last three hundred years as a montage it blinks by on fast-forward: first individual artisans sitting in their houses, their deft fingers flowing, and then an assembly line with many hands, hands young and old and missing fingers, and then later only adult intact hands as the machines get larger, safer, more efficient, with more blinking buttons and lights, and then the machines themselves join the line, at first primitive in their movements, but still the number of hands decreases further, until eventually there are no more hands and it is just a whirring robotic factory of appendages and shapes; and yet even here, if zoomed out, there is still a spark of human consciousness lingering as a bright bulb in the dark, for the office of the overseer is the only room kept lit. Then, one day, there’s no overseer at all. It all takes place in the dark. And the entire thing proceeds like Leibniz’s mill, without mind in sight.

I think that’s true about everything in the 21st century, not just factories, but also in markets and financial decisions and how media gets shared; in every little spot, human consciousness has been squeezed out. Yet, decisions are still being made. Data is still being collected. So necessarily this implies, throughout our society, at levels high and low, that we’ve been replacing generalizable and robust human conscious learning with some (supposedly) superior artificial system. But it may be superior in its sensitivity, but not in its overall robustness. For we know such artificial systems, like artificial neural networks and other learning algorithms, are especially prone to overfitting. Yet who, from the top-down, is going to prevent that?

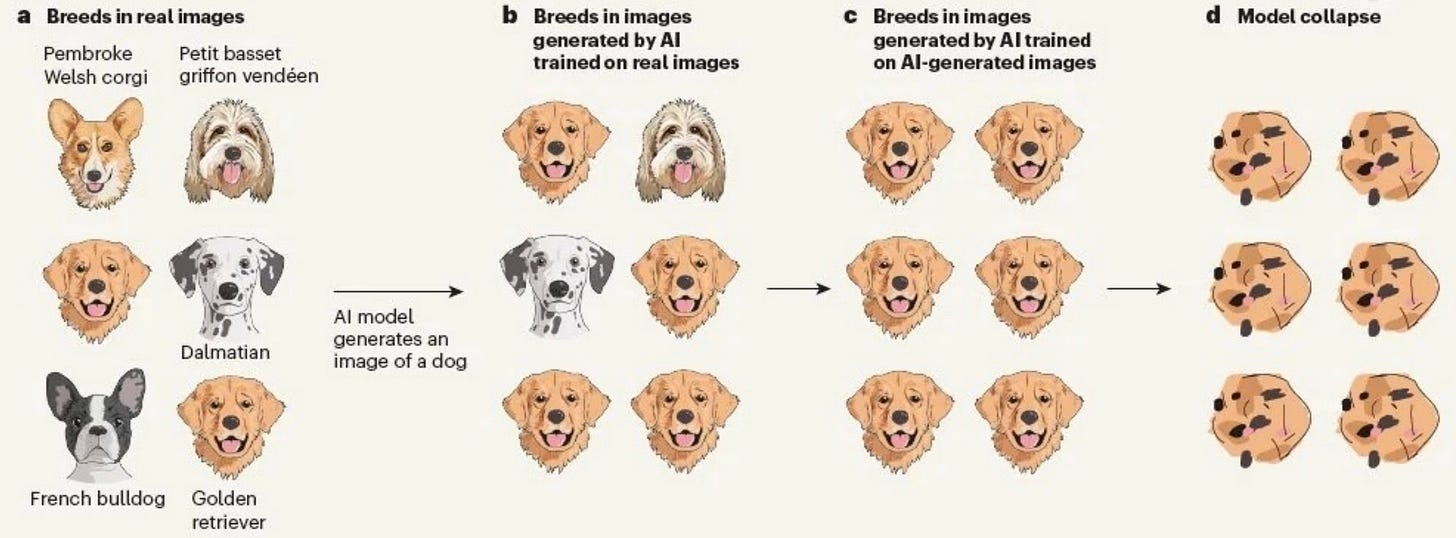

That this ongoing situation seems poised to get much worse connects to another recent piece, “The Platonic Case Against AI Slop” by Megan Agathon in Palladium Magazine. Worried about the current and future effects of AI on culture, Agathon worries (along with others) that AI’s effect on culture will lead to a kind of “model collapse,” which is when mode collapse (as discussed earlier) is fed back on itself. Here’s Agathon:

Last year, Nature published research that reads like experimental confirmation of Platonic metaphysics. Ilia Shumailov and colleagues at Cambridge and Oxford tested what happens under recursive training—AI learning from AI—and found a universal pattern they termed model collapse. The results were striking in their consistency. Quality degraded irreversibly. Rare patterns disappeared. Diversity collapsed. Models converged toward narrow averages.

And here’s model collapse illustrated:

Agathon continues:

Machine learning models don’t train on literal physical objects or even on direct observations. Models learn from digital datasets, such as photographs, descriptions, and prior representations, that are themselves already copies. When an AI generates an image of a bed, AI isn’t imitating appearances the way a painter does but extracting statistical patterns from millions of previous copies: photographs taken by photographers who were already working at one removal from the physical object, processed through compression algorithms, tagged with descriptions written by people looking at the photographs rather than the beds. The AI imitates imitations of imitations.

I think Agathon is precisely right.2 In “AI Art Isn’t Art” (published all the way back when OpenAI’s art bot DALL-E was released in 2022) I argued that AI’s tendency toward imitation meant that AI mostly creates what Tolstoy called “counterfeit art,” which is the enemy of true art. Counterfeit art, in turn, is art originating as a pastiche of other art (and therefore likely overfitted).

But, as tempting as it is, we cannot blame AI for our cultural stagnation: ChatGPT just had its third birthday!

AI must be accelerating an already-existing trend (as technology often does), but the true cause has to be processes that were already happening.3

Of course, when it comes to recursion, there’s a longstanding critique that we were already imbibing copies of copies of copies for a lot of the 21st century. Maybe this worry goes all the way back to Plato (as Agathon might point out), but certainly it seems that the late 20th century into the 21st century involved a historically unique removal from the real world, wherein culture originated from culture which originated from culture (e.g., people’s life experience in terms of hours-spent was swamped by fictional TV shows, fannish re-writes of earlier media began to dominate, and so on).

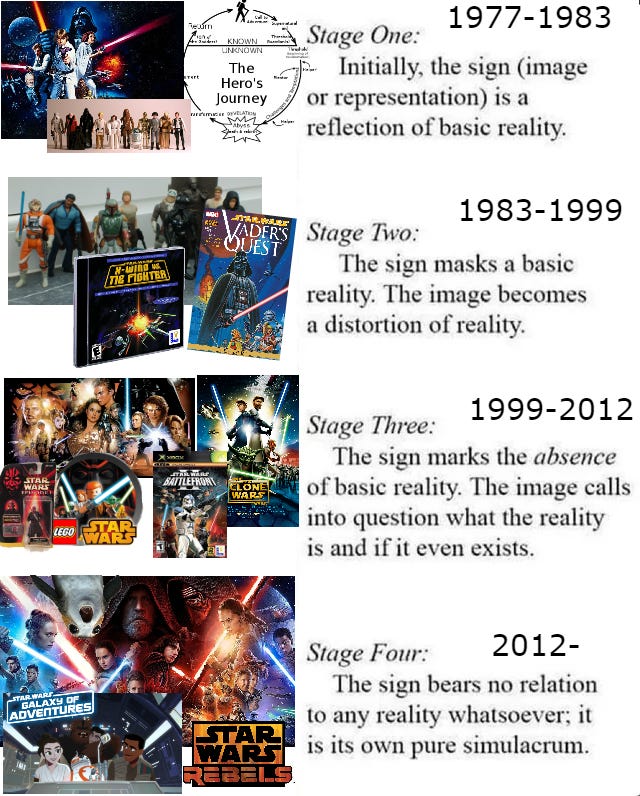

Plenty of scholars have written about this phenomenon under plenty of names; perhaps the most famous is Baudrillard’s 1981 Simulacra and Simulation, proposing a recursive progression of semiotic signification. Or, to put it in meme format:

So even beyond all the improvements in capitalistic and technological efficiency, and the rise of markets everywhere and in everything, the 21st century cultural production is also "efficient" in that it takes place at an inordinate "distance" from reality, based on copies of copies and simulacra of simulacra.

“Help, I’m stuck in-distribution and I can’t get out!”

The 21st century has made our world incredibly efficient, replacing the slow measured (but robust and generalizable) decisions of human consciousness with algorithms; implicitly this always had to involve swapping in some process that was carrying out learning and decision making in our place, but doing so artificially. Even if it wasn't precisely an artificial neural network, it had to, at some definable macroscale, have much the same properties and abilities. Weaving this inhuman efficiency throughout our world, particularly in the discriminatory capacity of how things are measured and quantified, and the tight feedback loops that make that possible, led to overfitting, and overfitting led to mode collapse, and mode collapse is leading to at least partial model collapse (which all leads to more overfitting, by the way, in a vicious cycle). And so culture seems to be ever more restricted to in-distribution generation in the 21st century.

I particularly like this explanation because, since our age is one of technological, machine-like forces, its cultural stagnation deserves a machine-like explanation, one that began before AI but that AI is now accelerating.

I’ll point out that this not just about crappy cultural products. If some (better, more nuanced, ahem, book-like) version of this argument is correct, then our cultural stagnation might be a sign of a greater sickness. An inability to create novelty is a sign of an inability to generalize to new situations. That seems potentially very dangerous to me.

Notably, cultural overfitting does not necessarily conflict with other explanations of cultural stagnation.4 One thing I always find helpful is that in the sciences there’s this idea of levels of analysis. For example, in the cognitive sciences, David Marr said that information processing systems had to be understood at the computational, the algorithmic, and the physical levels. It’s all describing the same thing, in the end, but you’re explaining at one level or another.

So too here I think cultural overfitting could be described at different levels of analysis. Some might focus on the downstream problems brought about by technology, or by monopolistic capitalism, or the loss of weirdos and idiosyncrasies who produce the non-overfitted, out-of-distribution stuff (who are, in turn, out-of-distribution people).

Finally, what about at a personal and practical level? People act like cultural fragmentation and walled gardens are bad, but if global culture is stagnant, then we need to be erecting our own walled gardens as much as possible (and this is mentioned by plenty of others, including David Marx and Noah Smith). We need to be encircling ourselves, so that we’re like some small barely-connected component of the brain, within which can bubble up some truly creative dream.

There are lots of sources here but I’m probably missing a ton of other arguments and connections. Unfortunately, that’s… kind of what the book proposal was for.

I think Agathon’s “The Platonic Case Against AI Slop” is also right about the importance of model collapse at a literal personal level. She writes:

So yes, AI slop is bad for you. Not because AI-generated content is immoral to consume or inherently inferior to human creation, but because the act of consuming AI slop reshapes your perception. It dulls discrimination, narrows taste, and habituates you to imitation. The harm lies less in the content itself than in the long-term training of attention and appetite.

My own views are similar, and the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis tells us that every day we are forever learning, our brain constantly being warped toward some particularly efficient shape. If learning can never be turned off, then aesthetics matter. Being exposed to slop—not just AI slop, but any slop—matters at a literal neuronal level. It is the ultimate justification of snobbery. Or, to give a nicer phrasing, it’s a neuroscientific justification of an objective aesthetic spectrum. As I wrote in “Exit the Supersensorium:”

And the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis explains why, providing a scientific justification for an objective aesthetic spectrum. For entertainment is Lamarckian in its representation of the world—it produces copies of copies of copies, until the image blurs. The artificial dreams we crave to prevent overfitting become themselves overfitted, self-similar, too stereotyped and wooden to accomplish their purpose…. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the works that we consider artful, if successful, contain a shocking realness; they return to the well of the world. Perhaps this is why, in an interview in The New Yorker, the writer Karl Ove Knausgaard declared that “The duty of literature is to fight fiction.”

I’m aware that there are debates around model collapse in the academic literature, but I’m not convinced they affect this cultural-level argument much. E.g., I don’t think anyone is saying that culture has collapsed to the degree we see in true model collapse (although maybe some Sora videos count). Nor do I think it accurate to frame model collapse as entirely a binary problem, wherein as long as the model isn’t speaking gibberish model collapse has been avoided (essentially, I suspect researchers are exaggerating for novelty’s sake, and model collapse is just an extension of mode collapse and overfitting, which I do think are still real problems, even for the best-trained AIs right now).

Another related issue: perhaps the Overfitted Brain Hypothesis would predict that, since dreams too are technically synthetic data, AI’s invention might actually help with cultural overfitting. And I think if the synthetic data had been stuck at the dream-like early-GPT levels, maybe this would be the case, and maybe AI would have shocked us out of cultural stagnation, as we’d be forced to make use of machines hilarious in their hallucinations. Here’s from Sam Kriss again:

In 2019, I started reading about a new text-generating machine called GPT…. When prompted, GPT would digest your input for several excruciating minutes before sometimes replying with meaningful words and sometimes emitting an unpronounceable sludge of letters and characters. You could, for instance, prompt it with something like: “There were five cats in the room and their names were. …” But there was absolutely no guarantee that its output wouldn’t just read “1) The Cat, 2) The Cat, 3) The Cat, 4) The Cat, 5) The Cat.”

….

I ended up sinking several months into an attempt to write a novel with the thing. It insisted that chapters should have titles like “Another Mountain That Is Very Surprising,” “The Wetness of the Potatoes” or “New and Ugly Injuries to the Brain.” The novel itself was, naturally, titled “Bonkers From My Sleeve.” There was a recurring character called the Birthday Skeletal Oddity. For a moment, it was possible to imagine that the coming age of A.I.-generated text might actually be a lot of fun.

If we had been stuck at the “New and Ugly Injuries to the Brain” phase of dissociative logorrhea of the earlier models, maybe they would be the dream-like synthetic data we needed.

But noooooo, all the companies had to do things like “make money” and “build the machine god” and so on.

One potential cause of cultural stagnation I didn’t get to mention, (and also might dovetail nicely with cultural overfitting), is Robin Hanson’s notion of “cultural drift.”

If dreams are the cure to our overfitting on our individual learning, then works of art are the dreams of the culture. Part of the explanation for an overfitted culture is a deficiency of dreams (which is also caused by the overfitted culture--it's a feedback loop).

I often complain to family and friends that algorithmic recommendations on Spotify etc. have completely broken down because the algorithms are now learning from their own recommendations. I listen to artist A, so Spotify thinks that I will like artist B because lots of people that listen to artist A also listen to artist B. But at this point in the history of algorithmic content, people that listen to artist A listen to artist B *because Spotify suggested it*. This creates a downward spiral, maybe something like a model collapse of recommendation engines where you are just being recommended music which represents the average of whatever genre you're spending the most time in.

The reason this is so awful is that artists now are slave to these recommendations. Human consciousness has been all but removed from the process by which artists "make it" (of course not entirely because, of course, labels still pay to have their artists recommended by Spotify) and instead they are mostly doing whatever they can to be picked up by Spotify's recommendation algorithm or TikTok creators that will make their song viral through TikTok's algorithm. The result is that artists are encouraged to make average-sounding music, because that's what's recommended by the algorithm. Not because anyone wants that, just because of the dynamics of such a system.

Spotify is just the place where this is happening most acutely, but clearly it's happening with movies and books as well.

I have some hope that eventually the tide will turn and people will become so sick of the stagnancy that they will begin to actively seek out actual cultural dreams, and slowly they will start to be encouraged even more so than ever before once we have some awareness of their actual importance.

I would buy and read this book. This essay alone contains the seeds for a hundred new lines of inquiry and exploration.